Persuasion in Ancient Greece

Andrew Scholtz, Instructor

Informational Pages. . .

List of Terms

Here are some more or less common terms (for this course, I mean) with

definitions. (A few ancient personages are thrown in for good measure.)

Achaean. = Greek.

Acropolis. "High city," the citadel (defended high ground) within many ancient Greek cities. Often the religious center of a city. The most famous acropolis is the Athenian Acropolis.

agon. Contest, debate, jury trial. Also a regular feature of Greek drama - a pair of characters locking horns in debate. That applies to comedy as much as to tragedy. The agones of Greek drama become, therefore, laboratories in peitho.

agora. In early poetry: "gathering place," "meeting," "assembly," "speech." In later usage agora meant "marketplace." See also "ekklesia."

akolasia. "Intemperance," "immoderation," "excess," "lack of self-control." Oligarchs tended to associate this quality with democracy and the demos. See also sophrosune.

amnesty. In Greek, amnestia, literally "non-rememberance." In 403, following the oligarchic coup of 404, it became necessary for Athenians wishing to rejoin the democracy to swear an oath of non-rememberance or "amnesty." The actual oath itself was ou mnesikakeso, "I shall remember no wrong." That is, the swearer swore that he (not she) would not seek vengeance, whether through the courts or otherwise, for wrongs suffered as a result of the coup. That made it possible for supporters of democracy to live side-by-side with those complicit in oligarchy - it prevented the re-outbreak of stasis. But, with smolering resentments and lawsuits providing a screen for the settling of old scores, the suppression of overt vengeance placed a strain on the consensus (homonoia) that it was supposed to bolster.

ananke. Compulsion, necessity. See also bia.

anaphora. See epanaphora.

anastrophe.when a colon begins with the same (or more or less the same) word or phrase the previous ended with: "The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors," Lincoln First Inaugural.

antilogic. "Antilogic" does not mean something illogical. Rather, tekhne antilogike is the "technique of constructing opposed arguments" (anti "in opposition" + logos "discourse," "argument"). For instance, starting with the proposition that Helen of Troy is to be blamed for the Trojan War, the art of constructing an argument that contradicts, or is at least contrary to, the starting argument (logos), the end result therefore being an argument (logos) maintaining that Helen was in fact not to blame. (Compare Gorgias' Helen.) Eristic would then be skill (potentially involving any number of techniques) at making either of those two arguments appear more convincing, irrespective of intrinsic truth. (Dialectic would be the art of showing which if either of the two logoi actually was the true one.)

Antirhetoric. See the "rhetoric of antirhetoric."

antistrophe. The same word or words at the ends of successive cola ("to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together," King I Have a Dream).

antithesis. Phrases and / or sentiments whose contrast is set in high relief: "And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country" (Kennedy Inaugural Address)

Aphrodite. Greek goddess of love (and other things, as we shall see). AKA Cypris (Kypris). Aphrodite, it seems, could also figure as a goddess interested in politics. So, for instance, we hear of Aphrodite Pandemos (sort of "the people's Aphrodite," maybe "everyone's Aphrodite") as a goddess enjoying cult commemorating the (mythological!) foundation of the Athenian state (Pausanias 1.22.4; Peitho readings). But we also hear of this same Aphrodite as a goddess connected with prostitution, which creates an interesting problem in interpreting this particular cult.

aporia. Doubt or uncertainty as a rhetorical pose.

apragmosune. "Modesty," "quietism," "non-meddlesomeness." Or else "useless inactivity," "indolence." (Cf. polupragmosune)

archon. At Athens, one of the 9 principal city officials. In the 400s and 300s, chosen by lottery; serve mostly in a cermonial capacity. More significant are the generals.

Areopagus. he boule he tou areiou pagou, "the council of the Hill of Ares," AKA the Areopagus council, memorably introduced by Aeschylus into his courtroom drama of 458, the Eumenides, where it sits in judgement over Orestes at the latter's homicide trial at Athens. The Areopagus originally functioned as the aristocratic "upper house" of the Athenian state in the early archaic period. It was composed of former archons who joined on conclusion of office; membership thereafter was for life. It cannot, therefore, be viewed as a democratic body, a fact complicating interpretation of its role in Aeschylus' drama. Traditionally regarded as protector of Athens' laws, the Areopagus seems to have held veto power over assembly legislation, a power it exercised probably until the reforms of 461. It may also have prepared legislative agenda for the assembly, though that function will have been transferred by Solon to his new Council of 400 in the early 500s. In 461, the Areopagus' oversight function over assembly decrees seems to have been removed completely, thus furthering the transition to full democracy. But it arguably will have retained some sort of aristocratic character at least untile 458/7, when archons ceased to be chosen exclusively from the higher economic classes. After 461, when the council's political powers were curtailed, it nevertheless retained judicial functions: oversight over certain murder trials (intentional homicide) and other things (mistreatment of the sacred olive trees). See also boule.

arete. Excellence, virtue. Protagoras seems to have claimed to teach pupils political arete, the qualities needed to participate constructively in governing.

Argos. Greek city. Mythical-legendary Argos famous for Agamemnon, Clytaemestra, Electra, Orestes, etc. Classical-historical Argos was a democracy often allied to Athens and at war with Sparta.

"Arian". = Persian.

arkhe. (Literally "beginning" or "leading position.") Rule, power, empire, political office.

assembly. See ekklesia.

Athens. Greek city state, located in mainland Greece, chief city in Attica, famous for democracy. In the later fifth century BCE, fought Sparta in the Peloponnesian war.

Atreids, Atreidai. Menelaus and Agamemnon,sons of Atreus.

bia. Violence, force, threats, coercion. See also ananke. Often understood as the opposite of peitho, yet sometimes as a kind of peitho.

boule (plural boulai). "Council," a legislative body smaller than the assembly (demos, ekklesia) of a Greek city state (polis), whether that's Athens or another one.

- Very early Greek boulai will have been staffed by elders serving as advisers to kings. (Probably the function of the Athenian Areopagus in its earliest form)

- Later (archaic, classical) boulai will have typically been charged with preparing the agenda for assembly (ekklesia) meetings

- Oligarchic boulai were typically small and staffed by the elite holding office for long periods. They often held greater power than the popular assembly

- Democratic boulai typically were larger bodies, more representative of the citizenry as a whole than in the case of boulai. Members of more democratic organized boulai will have held office for shorter periods, typically, one year

- The boulai at Athens were

- The Areopagus

- Solon's boule of 400 (100 members from each of Solon's four tribes), in force 593-507

- Cleisthenes' boule of 500 (50 members from each of Cleisthenes new 10 tribes), from 507 into Roman times

- The Cleisthenic boule of 500 was open to all economic classes but the lowest (thetes), male citizens 30 or older. It met every day except state holidays. Election by lottery starting at latest ca. 450. Probably no later than late 400s, pay for council members. Starting around 400, council service limited to two terms. In addition to agenda preparation, varied administrative oversight. Council agendas under the radical democracy allowed much scope to assembly debate. Agendas did not have to make specific recommendations; they could be modified at assembly meetings by motion of citizens; private citizens could suggest agenda items to the boule. See probouleusis

captatio

benevolentiae. Captatio benevolentiae is Latin for the effort to curry goodwill.

As a technical term of

rhetoric, it means the effort to win a favorable hearing from one's

audience; the things one has to say to establish a connection with

one's audience; one's audience-bonding affirmations; also affirmations

to avoid ill-will. Our translation of Aristophanes Knights (Sommerstein, pub'd Penguin) makes fun of, among other things, just such attempts to curry good will with one's audience (p. 87 et passim).

These typically take

the form of topoi like:

- "I share your (the demos') values"

- "Your friends are my friends; your enemies, my enemies"

- "My ancestors and I have always endeavored to benefit you"

- (political topos) "Though I say what you do not want to hear, it is out of a sense of devotion to your well-being"

- (judicial topos) "I pray that you show me the same goodwill that I have always shown you" (Demosthenes On the Crown)

- (judicial topos) "I

mind my own business (am apragmon)

and do not ordinarily have to speak in court." Also,

"Please forgive my lack of polish; I'm not used to speaking

in court"

- I.e., "I'm an ordinary, well-behaved citizen: not the sort likely to spend much time in court, nor to deceive you with rhetoric"

Captatio benevolentiae, which usually happens at the beginning of a speech (the prooimion), seems typically to involve speech acts aimed at establishing ideological connections with an audience (compare Austin, Vološinov, Ober). Such speech acts could, however, be viewed as capable of exercising a kind of control over audiences. Hence anti-rhetorical strategies like the demophilia topos, ones designed to spin an opponent's audience bonding as illegit manipulation.

centripetal, centrifugal. Relates to Bakhtinian notions of dialogue. Centripetal discourse: "center-seeking," restrictive, normative discourse. Centrifugal discourse: "center-fleeing," non-restrictive, pluralistic discourse. Click here for more.

charis. See kharis.

charisma. Or "charismatic authority," Weberian concept. "Legitimate domination" based on the strength of a leader's seemingly magical or exceptional qualities, personality, perceived divine mandate - that whatever-it-is that seems to confer legitimacy on his/her leadership.

Charites. The goddesses of kharis.

citizen. In Greek, polites. At Athens, citizens were the legitimate children of legitimate Athenian citizen-fathers. After Pericles' citizenship reform in 450/1, both parents had to be citizens.

cleruchy. The settlement of Athenian citizens (typically poorer ones) on captured or annexed foreign territory.

colon (plural, "cola"). A word-grouping understood not as a grammatical but rhetorical unit. A colon can be as short as a single word, as in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar: "Friends, Romans, Countrymen" (that's a tricolon, three cola in a row). Cola can be phrase-units, as in the following: "of the people, by the people, for the people" (Lincoln, another tricolon). Or it can consist of clauses: "we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow" (Lincoln).

constative. Relates to speech-act theory; click here.

content versus force. Relates to speech act-theory; click here.

Cypris. = Aphrodite. See further.

decrees. In Greek, psephismata (singular psephisma). These are the resolutions passed by the assembly, usually for a particular purpose, but at times with the effect of a more permanent enactment. Compare/contrast nomos.

Delian League. See Plutarch Themistocles study guide.

Delphi. AKA Pytho, location of the most famous of all ancient oracles: the Delphic Oracle. Sacred to Apollo.

Delphic Oracle. See above, "Delphi."

demagogue, demagoguery, demagogy (dēmagōgos, dēmagōgia). The Oxford English Dictionary, for its definition 2 of "demagogue," says that the word refers to "a leader of a popular faction, or of the mob; a political agitator who appeals to the passions and prejudices of the mob in order to obtain power or further his own interests; an unprincipled or factious popular orator." That's how it's commonly used today and it is a sense that could apply to the ancient Greek term dēmagōgos, where English "demagogue" comes from.

But the Greek word, not unlike the derived abstract noun dēmagōgia (whence English "demagoguery"), could also refer something connotationally neutral: a leader of the people, even a good one, under democracy. In Plato's Gorgias, Callicles uses it as an insult — "demagogue," then, as anyone who indulges in captious rhetoric. But it won't have always meant that.

Still, in the 300s BCE it seems to have come to mean mostly bad things. Thus Aristotle, writing in the Politics, defines "demagogue" (dēmagōgos) as a "flatterer of the people" (tou dēmou kolax, 1313b40-41).

In closing, I quote Simon Hornblower: "On the most favourable view, demagogues were the 'indispensable experts', particularly on financial matters, whose grasp of detail kept an essentially amateur system going. Certainly inscriptions, our main source of financial information about Classical Athens, help correct the hostile picture in Thucydides and Aristophanes. But it has been protested that demagogues worked by charisma not expertise" (Oxford Classical Dictionary s.vv. "demagogues, demagogy).

deme. Athenian administrative unit: one of the villages of Attica or neighborhoods of Athens. (The Greek word is demos, which see also).

democracy. demokratia in Greek = "power in the hands of the demos" (the people). The "radical democracy" at Athens involved the direct involvement of the voting citizenry in many aspects of government. See also isonomia, isegoria.

demophile, demophilia, demophilia topos. I have used the term "demophile" to refer to a politician who seeks favor by stating his love (philia) for the people (demos) of Athens (for the polis, for "you," the audience, etc.). As for "demophilia," it refers to any style of politicking featuring such claims.

In my research (Concordia Discors), I have found that it was extremely rare — virtually never done — to say such things in a publicly delivered speech under the Athenian democracy. It was, however, very common to say that others make such claims. I call that the demophilia topos: "so-and-so says he loves you (the demos, the polis), yet his actions contradict his words."

Thus the demophilia topos "spins" an opponent's captatio benevolentiae as insincere audience-bonding, as speech-acts intended to forge a manipulative love-connection ("I love you!"). Thus it represents a strategy to control the discourse: it misrepresents the "misrepresentations." Compare use of the term demotikos.

demos. The people of a city state (polis) like Athens - i.e., the entire citizen body. Alternatively, the adult voting males among the citizenry - i.e., the people's assembly, or ekklesia. The word can also refer to a "deme," or administrative unit within the Athenian polis. See also "deme."

demotikos. "Democrat,"

"member of the democratic faction," "true-blue demos-lover."

An ideologically loaded term, it comes to the fore in the period

following the 404/3 oligarchy. Thus to have been demotikos during that period was like being in the Resistance during the Nazi

occupation of France. (Compare philodemos.)

It was, then, high praise

to call someone else demotikos, yet to call onself that seems never to have been done. Hence a "demotikos topos" very similar to the demophilia

topos: "So-and-so

goes before you and claims to be demotikos, yet is nothing

of the sort!"

dialectic in Plato and Aristotle. Dialektikē tekhnē, the "art of dialectic." The term "dialectic" derives from Greek dialegesthai, "to engage in dialogue." Though for Plato, Aristotle, and others, it can refer to abstract processes of thought, it never wholly loses touch with the idea of a back-and-forth aiming at a more perfect understanding of things.

Plato seems to mean two things by dialectic:

- A process of definition, whereby a true understanding of what a thing is (what its ideal form is and, beyond that, what the nature of the real ultimately is) is achieved through exchange of ideas between discussants (i.e., through dialogue), and through the critical examination of those ideas (elenchus); and

- A process of collection and division, grouping together and distinguishing apart, whereby we gain insight into what makes things of a kind the same, and different kinds of things different.

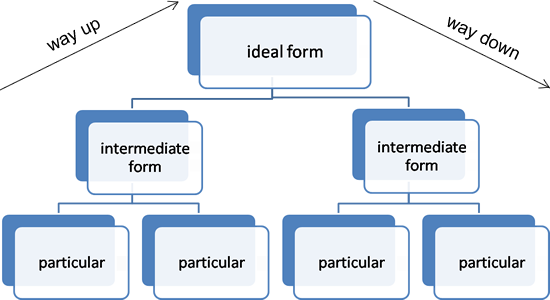

Number 2 needs further comment. There, dialectic can be thought of in two ways, namely, as

- The "way up" from particulars to the general, or "synoptic" dialectic; and

- The "way down" from the general toward particulars — "diacritic" dialectic, where the endpoint or "term" will be intermediate forms riding just above particular instances.

For Plato, that's pretty much what true knowledge is all about. See also forms, theory of.

In Aristotle, dialectic is very similar, though for him, it represents something other than a path to Truth with a capital "T." Dialectic for Aristotle uses cogent logic to reason from widely held or authoritative opinions. Its conclusions are necessary even if its premises are not.

dialectic in modern authors. A kind of ongoing debate or negotiation, not so much between individual persons as between world views of different segments of society, classes, etc. So, for instance, Ober sees ancient Athenian democracy as a dialectical interaction between mass and elite, interest groups, according to Ober, each embodying a distinct perspective. See also dialogue.

dialogue. Dialogical, dialogism.

Social interaction transacted as conversations between persons -

ties forged and validated via ideology, with ideology itself as an ongoing and evolving conversation. Utterance as inherently

directed toward reception, evaluation, and response by another.

A concept important for Bakhtin and his group (including Vološinov).

See also ideology.

See further here (pdf).

dicanic. One of Aristotle's three genres of oratory, dicanic or judicial oratory consisted of speeches intended for delivery in court. Aristotle says that dicanic concerned itself with accusation and defense regarding past action.

dikasterion (plural dikasteria). One of the "people's courts" (Heliaia) at Athens. A "dicast" was a juror; "dicastic pay" was pay for jury service. Given its staffing from the people (male, adult citizens) at large, plus the institution of jury pay, it can be regarded as one aspect of Athens' democracy. See more under Heliaia.

dike. ("DI-kay.") Justice, judicial penalty,

public prosecution. Dikaiosune or to dikaion in prose are the words typically us

ed for justice itself. Dike is an important theme in the Oresteia.

disfranchisement. See franchise.

dolos. Trick(ery), deceit, cunning. Can be a modality of peitho.

doxa. Opinion as opposed to true knowledge; appearances, impressions, subjectivity. Seeming as opposed to being. Also, one's reputation, good or bad. See the sophists readings.

dystopia. An exemplary "bad place," compare utopia.

eikos (to eikos). See "Probability, argument from."

ekklesia. The people's assembly at Athens, also known as the demos. (Contrast boule.) Resolutions of the assembly were called psephismata, (English "decrees"). See also agora.

elenchus. (elenkhos, literally "accusation" or "refutation.") The critical examination of a thesis or definition, and often leading to the invalidation or refutation of that thesis or definition. Socratic question-and-answer often takes the form of elenchus; we can think of it as an ancient counterpart to critical thinking. See also dialectic.

entekhnos pistis. In Aristotle's Rhetoric (pp. 137 ff.), an "artful argument," one leveraging the "value added" of technical rhetoric, as opposed to the "artless proofs" that, in a sense, speak for themselves: physical evidence, testimony, turture.

enthymeme. (From Greek enthumēma, "thought," "reasoning," "argument.") In Aristotle, an enthymeme is a syllogism of a particular type. As in the case of the dialectical syllogism, its premises are probable as opposed to obvious, self-evident, or empirically confirmable. Thus enthymemes combine logic with to eikos, proof by probability. Enthymemes also tend to leave it up to the audience to put the pieces together, i.e., elements of the reasoning are implied rather than stated. Enthymemes tend, furthermore, to rely on commonly accepted notions. For Aristotle, enthymemes are the basis of rhetorical logic, the logic of the crowd.

epanaphora. The use of the same word or words at the beginnings of successive cola: "Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana" (King I Have a Dream).

epideictic. One of Aristotle's three genres of oratory, epideictic was "show" or "display" oratory (epideiknunai "to show," epideiknusthai "to show off"). Aristotle says that the topics of epideictic were praise and censure, and the aim, to display an orator's skill. (According to Isocrates, speeches of an epideictic cast were more poetic and more elevated than courtroom speaking, or dicanic.)

Epideictic often took the form of ceremonial oratory: funeral orations, festival orations, etc. But the encomium, the "praise" speech, was also a species of epideictic. Epidexis and epideictic could draw into a close nexus, as epideictic speeches very often were in fact sample speeches to be read rather than delivered live.

epideixis. Plural epideixeis,

Greek for "demonstration," "proof" (epideiknunai, "to show").

The term could also

refer to "mock" assembly-, courtroom-, etc. speeches not

intended for actual delivery, but for "demonstrating"

a given argument, a mode of argumentation, a rhetorical style, rhetorical

skill, and so on. Examples: Gorgias' Helen, Antiphon's Tetralogies,

pseudo-Xenophon's (the "Old Oligarch's") Constitution

of the Athenians.

Some scholars view the

speeches in Thucydides as closely akin to sophistic epideixeis.

See also sophist.

epilogos. The "after-speech," "epilogue," - the often stirring finish to a speech.

epithet. An added name (often descriptive) to go along with a divinity's main name: Aphrodite Pandemos = "Aphrodite For Everyone" or "Aphrodite of the Whole People."

erastes. A man who feels eros for someone - or something - else. See also pederasty.

eristic. From eris, "strife," "quarrel." The art of debate - not the same as antilogic or dialectic. I.e., the "tricks of the trade" as opposed to the theory that lies behind Protagoras' and others' theories of logos and argumentation (antilogic, dialectic). See also sophistic.

eromenos. The (male) beloved. A female beloved was an eromene. See also pederasty.

eros. "Love," "desire," "lust," sexual or otherwise (greed, hunger, ambition, etc.), often overpowering. Capitalized, "Eros" refers to the god of love/lust. In the classical period, virtually identical to himeros.

eunoia. "Goodwill," "kindness," "benevolence." Can be used, among other things, in the context of politics (a leader showing goodwill to the city/people) and of sexual courtship (a lover deserving because benevolent toward his beloved).

eunomia. "Good order," in some ways, the opposite of stasis or "political discord."

force (as in "content versus force"). Relates to speech act-theory; click here.

forms, theory of. In Plato, the idea that each and every thing we encounter in the world we experience, the here-and-now (the phenomenological world), represents an imperfect instance of a more perfect something else, the "form" (eidos) or "idea" (idea) of that thing.

These "forms" or "ideas" are generally understood to possess the following characteristics:

- They exist in a realm beyond the here-and-now

- They are immaterial, and thus cannot be grasped by the senses, only by thought

- They are more real, more perfect, than the things of the here-and-now

- They are the realities of which particular instances are but imperfect facsimiles

Think of it this way. You have a whole lot of chairs you physically sit in, some better, some worse, none perfect. But somewhere out there is "Chair" as a kind of blueprint for all the chairs we experience. Yet it is this idea of "Chair" that is the real chair, the perfect template for all those sorry instances of "chair" in our world. Yes, you can see and grasp the latter, whereas you can only reason the the former. But the former is really real; the latter, only partly so, i.e., only insofar as a given instance of "chair" partakes of the ideal form of "Chair."

In Plato, moral and aesthetic qualities also have their ideal forms: the form of the beautiful, the form of the good, and so on. It is the Form of the Good that is the ultimate Form of all Forms.

See also dialectic.

franchise. Citizenship rights - the rights and privileges of an adult male citizen (voting, owning property, etc.) Disfranchisement (atimia) is the removal of those rights from a person or persons.

gynaecocracy. From gunaikokratia, "political power (kratos) exercised by women (gunaikes)," which is to say, not men. A theme hinted at in Aristophanes' Lysistrata, and explored to the full in his Assemblywomen.

hegemony. Leadership dominance. The power to influence decisively a group's actions, policies, etc.

Heliaia, Eliaia. Court instituted by Solon, it was - or it was meant to stand for - the demos meeting as a jury. Aristotle calls the Heliaia democratic because it allowed defendants to appeal an official's judgment to a body representing the people. It later became the dikasteria, the "People's Courts."

Helen. "The face that launched a thousand ships," i.e., Menelaus' wife and Paris' lover - the woman over whom the Trojan war was fought. See further here.

Hellas. Greek for "Greece."

Hellen. Greek for "Greek," plur. Hellenes. (This has nothing to do with the proper name "Helen.") Also the adjective Hellenic.

himeros. See Eros

Hermes. Greek god of communication, commerce, trickery, boundaries, etc. See further.

herm. A "Hermes" image, i.e., boundary marker consisting of stone post with phallus and head of Hermes. These typically stood outside entryways, seemingly with the function of scaring off would-be intruders and protecting those within.

hetairos, hetaireia. Hetairos: "companion," "comrade." Hetaireia: usually anti-democratic political club; a group of like-minded anti-democratics banded together as a social and politcal unit. These become prominent in the final decades of the 400s; their machinations led to the establishment of oligarchy in 411.

hetaira. Same word as hetairos, only referring here to a woman. Thus a female "companion," a "courtesan" or high-priced prostitute. Compare porne.

homoioteleuton. Rhetorical (as opposed to poetic) use of end-rhyme, especially in combination with antithesis, isocolon, or parisosis ("we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate," Lincoln Gettysburg Address).

homonoia. homo- "same" + nous "mind," "thought" - i.e., homonoia is "like thinking," "consensus," "(political) harmony," "civic amity," "concord." I.e., the opposite of stasis. Starting about the end of the 400s in Greece, calls to homonoia in the state become frequent in our sources. See also stasis, amnesty.

hoplite. Heavy-armed soldier fighting

in close formation on land (the "hoplite phalanx"). Sparta

was renowned for its hoplites, Athens less so. A hoplite was required

to pay for his own weaponry (the "hoplite panoply": shield,

helmet, spears, etc.). At Athens, the wealthier and middle classes

- i.e., mostly large landowners and middling farmers - fought in

the ranks of the hoplites. The hoplites could therefore be regarded

as a political-economic interest group, heavily invested in the

well-being and territorial integrity of the polis. Since

hoplite warfare promoted coordinated maneuvers over individualism,

hoplite warfare could become a metaphor for civic solidarity.

Really wealthy citizens with income to own a horse might qualify

to join the cavalry (hippeis, "knights"), though

they fought with the hoplites, too. The poor, excluded from the

ranks of the hoplites, were paid to row the ships and to fight on

land among the light-armed auxiliaries, the "peltasts"

(see thetes).

ideas, theory of. For Plato's "theory of forms/ideas," click here.

ideology. American Heritage

Dictionary: "The body of ideas reflecting the social needs

and aspirations of an individual, group, class, or culture."

For this class, we shall recognize at least three refinements to that definition:

- The statements/narratives a group makes about itself to validate its claims to authority, control, or power over others

- The inner narratives by which individuals structure how they fit into society - how they embrace/reject the values, etc. they see there; how they conceptualize their respective roles and identities in the world they exist in

- That which is communicated when individuals form discursive communities with each other. Sort of like #2, only here, the structuring of the individual's relationship to society takes place interactively on the social, verbal, and rhetorical - i.e., external - planes

Ilium. = Troy.

illocution. See Speech-Act Theory and Dialogical Theory pdf.

Iron Law of Oligarchy. See Michels, Political Parties ("Chapter 2. Democracy and the Iron Law of Oligarchy") reading.

isegoria. Term formed of isos "equal" and -egoria "speech": "the right of all citizens to speak on matters of state importance in the assembly" (Ober Mass and Elite 78). Perhaps (but probably not) introduced at Athens by Cleisthenes in 508/7; surely in place by the early 450s. Considered by Athenians a "cornerstone of the democracy" (ibid. 79), it meant that issues would be debated - i.e., that competitions in peitho would take place in the assembly.

See also parrhesia, "frank speech."

isocolon. The balancing of successive cola with precisely equal numbers of syllables ("we can not de-di-cate, we can not con-sec-rate" [6 and 6]). Compare parisosis.

isonomia. Term formed of isos "equal" plus nomos "law": "equality before the law." Ober defines it thus: "equality of participation in making the decisions (laws) that will maintain and promote equality and that will bind all citizens equally" (Mass and Elite 75). Seems to have been a term employed during the Cleisthenic age (late 500s) as a way of referring to the new political order at Athens. In Alcmaeon - and according to Martin Ostwald - it means political equilibrium, balance between interest groups in the state (contrast stasis). See also democracy.

kalos inscription. That "so-and-so is beautiful," i.e., sexually attractive. Kalos inscriptions could be found as graffiti on walls and doors, painted on vases, etc.

kalos k'agathos. A label of commendation,

it can be translated "fine and noble," a "man of

quality," "top-drawer," a "gentleman."

(The plural is kaloi k'agathoi. The quality possessed by

such men is kalok'agathia.)

Earlier on and throughout,

this phrase designated the male members of the Athenian upper classes.

But, starting in the later 400s, it could also refer to any male Athenian citizen, but still by way of emphasizing his (supposedly)

aristocratic qualities. In other words, the sovereign demos as a whole as a quasi-elite class.

kharis. Attractiveness, allure,

charm (erotic and otherwise), grace, gratitude, favor, popularity

(including political), pleasure. Speakers often accuse one another

of speaking pros kharin, that is, of trying to speak in ways

that generate a pleasant "buzz" in one's audience. Compare: kolakeia, demophile, captatio benevolentiae.

Note that the English

word "charisma" derives ultimately from Greek kharis.

khoregia. A liturgy under which a wealthy citizen is obliged to fund a dramatic performance.

kinaidia, kinaidos. kinaidia: male sexual passivity. kinaidos: one who engages in kinaidia.

khroma. Latin color ("color"), i.e., "spin," the connotational associations you attach to a fact or circumstance (i.e., to make it look better or worse, depending on need).

koinonia, communalism. In Aristophanes' Assemblywomen, Praxagora, whom the sovereign women elect "generalissima," decrees the sharing of housing, of moveable property, of spouses and lovers, indeed of everything. This is koinonia or "communalism," a term that distinguishes what Praxagora institutes from Marxist socialism of the means of production.

kolakeia, kolax. Flattery, adulation,

excessive currying of favor, "brown nosing." kolax,

"flatterer," i.e., one who practises kolakeia.

The flatterer, a kind

of false friend, was a debased figure. Men who "mooched"

off the hospitality of wealthier citizens, who placed themselves

at the beck and call of their social and/or wealth superiors, who

performed favors in return for money and/or food - such men might

be labeled kolakes, "flatterers."

At the same time, the kolax could be thought of as trying to take advantage of

his victims: a con artist. So legacy hunters (people trying to get

themselves written into your will) are often labeled kolakes.

Politcians often accused

one another of flattering - appealing to the baser instincts of

- the demos. That charge is in fact a standard blame-topos.

Kypris. = Aphrodite. See further.

liturgy. E.g., trierarchy or khoregia. A liturgy was a duty imposed by the state on its wealthier citizens - the duty, that is, to fund this or that more or less expensive project. Liturgies could bring honor to those appointed to them, but they could also be crushingly expensive. If appointed to a liturgy you could go to court to challenge someone else to an antidosis wherein, if you won, your opponent either had to perform the liturgy or else exchange property with you.

locution. See Speech-Act Theory and Dialogical Theory pdf.

logographer. Greek: logographos. Professional speech-writer, esp. of speeches to be used in court.

logos. (Plur. logoi.) Account, story, speech, an individual speech; an argument. Also calculation, reason, rational thought, reasoned discourse, true story (versus myth), etc.

Loxias. = Apollo as god of prophecy. See further.

Lydia. One of the regions of Asia Minor (= modern Turkey). "Lydian" = one from Lydia. Can be an equivalent for "Trojan."

mekhane. "Mechanism," device, trick, expedient. The art of argument (eristic) can sometimes be presented as a repertoire of such "tricks."

metic. Greek metoikos. A "resident foreigner," like someone with a green card. At Athens, as typically elsewhere, metics were free and had some rights, but were recognized to be of lower status than citizens (though some metics could be quite wealthy), and could not own land. Metics had to register with the deme where they resided, and often were craftsmen, tradesmen, and merchants. Metics were also required to fight in the army.

monarchy. Greek monarkhia, "rule by a monarkhos," that is, "rule of one." Sometimes synonymous with tyranny.

nomos. "Law," "custom,"

"convention." In archaic Athens, nomoi (plur. of nomos) were statutes drawn up by specially empowered legislators

(Draco, Solon) to have permanent and general force. Earlier in the

400s, the assembly would enact nomoi; it was, though, more

characteristic of the Athenian assembly to enact decrees.

Starting in 403, and throughout the 300s, oversight of nomoi (enactment

and revision of them) was the job of boards of nomothetai,

or "legislators."

With the sophists, nomos combines the notions of "law," "custom,"

"convention" so as to refer to something approximating

modern notions of "constructed reality" or the "truth

regimes" that are both the prisms through which we view reality,

and the societal "rule books" in accordance with which

we operate as subjects in the world. (For this last, see also doxa.)

Contrast phusis.

nomothetai. In 300s BCE Athens, any board of "legislators" appointed by the Athenian assembly in a given year to revise or add to existing nomoi or "laws." From 403 on, nomoi (the city's standing "laws") and psephismata (ad hoc "decrees" passed by the assembly) were treated as separate forms of enanctment; see above.

okhlos. The "rabble." The supposedly low-class, unruly elements of the demos. The elements to which demagogues try to appeal.

oligarchy. oligarkhia in Greek = "power in the hands of the few," i.e., of a birth-elite (aristocracy) or wealth-elite (plutocracy).

ontology, ontological. "Ontology" is that branch of philosophy concerned with the fundamental nature of reality ("ontology," from on "being" and logos). "Ontological" is the adjective derived from it. Thus Parmenides was famously the author of "ontological" arguments proposing that reality ("what is") is a unity, unchanging and indivisible, uniform throughout and lacking any emptiness. ("Being is, but nothing is not," fr. 6 D-K.)

ostracism. A special vote, held by the Athenian demos, to determine whether a given individual ought to be required to live outside the territorial boundaries of the Athenian state for a period of ten years. Not exile, exactly, because no stripping of citizenship, etc., ostracism may have originally been instituted to prevent individuals from gaining too much power. It came, though, to be used as a weapon wielded by politicians against their enemies. Is worthwhile to research this in Ober Mass and Elite or others.

Paean. = Apollo as god of healing. See further.

Pallas. = Athena. See further.

Panathenaea, Panathenaic. Panathenaea, Panathenaic Festival, Panathenaic Procession. First, the Panathenaea are the same thing as the Panathenaic Festival. This festival, which celebrated Athena Polias ("Athena Who Potects the City"), also celebrated the unity and power of Athens. It was a yearly event, but every fourth year, it involved athletic, musical, and poetic contests and a grand procession. The Panathenaic procession, in which Athena's new robe (peplos) was annually conveyed to her temple on the Acropolis, called upon both Athenians and non-Athenians to take part.

pandemos. See "Aphrodite."

parisosis. The balancing of successive cola with nearly equal numbers of syllables ("we can not consecrate, we can not hallow," Lincoln Gettysburg Address; compare isocolon.)

paronomasia. "(Etymological) wordplay," i.e., the artful or witty use together of words sounding alike and (typically) of similar derivation, e.g., "Stars grinding, crumb by crumb, / Our own grist down to its bony face" (Sylvia Plath, All the Dead Dears — note "grinding" and "grist").

parrhesia. Perhaps best translated as "frank speech," parrhesia comes from roots meaning "to say everything," or better, to "to omit nothing," in other words, not to refrain from saying exactly what's on one's mind. Among ancient philosophers, Socrates ranks as one of two especially renowned for parrhesia. (The other was the Diogenes the Cynic.)

Now, parrhesia, as frank speech, had a double valuation. On the one hand, it could count as shameless speech, the willingness to say anything that came to mind, including inappropriate or offensive things.

On the other hand, parrhesia was the frank speech one expected from one's friends, those who really cared about one. It was also expected of democratic leaders, who were to speak their minds and not lie. Still, it could get one in trouble to speak freely before a body that, like the Athenian people, was capable of punishing one in various ways if it happened not to like what it heard.

In Plato's Gorgias, Socrates is characterized as using parrhesia with people, Callicles, as using kolakeia.

See also isegoria, "equal" or "free political speech."

patrios politeia. This is the idea of the "ancestral constitution," also "ancestral citizenship criteria." Either phrase will translate the Greek; for Athenians of the 400s and 300s BCE, the two pretty much mean the same thing.

In fact, patrios politeia was to all intents a purposes a political slogan, even a topos, available to anyone needing rousing, chest thumping theme.

- For oligarchs in the late 400s, it referred to the kind of government Athens enjoyed before it had been "corrupted" by radical democracy

- For democrats in the period following the oligarchic regime of 404 BCE, it referred to radical democracy lacking any property qualification for citizenship, the kind of democracy "our ancestors" lived under

- For all and sundry, whatever their political stripes, it meant that form of government, much better than the one "we" have "now," that our heroic forebears enjoyed "then"

pederasty. From pais "young person" + eros "desire," "love." The relationship between an older male erastes (lover) and a younger male eromenos (beloved). The relationship was symmetrical in that both parties were expected to feel affection (philia) for the other, but asymmetrical in that the older lover was dominant, the younger, subordinate. Eros (sexual desire) was to be felt only by the erastes. The sexual favors granted by the younger man were viewed as expressing gratitude for the mentoring provided by the older. Once the younger man's beard had grown in, he ceased to be sexually attractive, and the relationship was supposed to morph from something sexual to non-sexual peer friendship. See also eros.

peithein. "To persuade" - i.e., the verb form of peitho.

peitho. "Persuasion/persuasiveness" in various senses (verbal persuasion, eloquence, erotic seduction/seductiveness, bribery, etc. etc.), or the state of "conviction" (believing something) that is produced in a person. Also "obedience." Capitalized, "Peitho" refers to the goddess (or personification) "Persuasion." See also peithein.

Pelopidae. Descendents of Pelops, including, Atreus, Agamemnon, Menelaus, Thyestes, Aegisthus, etc.

Peloponnesian War. Sparta and its allies trying to end Athens' empire. 431-404 BCE. Sparta eventually won, but Athens eventually bounced back.

performative. See Speech-Act Theory and Dialogical Theory pdf.

perlocution. See Speech-Act Theory and Dialogical Theory pdf.

philia. Affection, love, friendship etc.

philodemos. "Demos-loving," i.e., a true-blue democrat (compare demotikos). Opposite: misodemos, "demos-hating."

philopolis. "City-loving," i.e., a patriot.

philos. Dear one, friend, etc. See philia.

Phoebus (Phoibos). = Apollo. See further.

phusis. "Nature" (root of "physics"), either the nature of an individual entity or of all entities as a whole (the "nature" of the universe, or just "nature"). With the sophists, phusis arguably came to mean something resembling the-way-things-are-irrespective-of-human-subject. Some modern scholars interpret this as a sophistic precursor to the notion of viewing reality from an essentialist perspective. See also nomos.

Piraeus. The harbor area for classical Athens. Many metics live there - also prostitutes.

pisteis. The "proofs" section of a speech: where a speaker proves his case.

pleonexia. "Greed," or the "seeking to have more," especially more than one deserves or more than is good for

Pnyx. Hill on which the Athenian assembly (demos, ekklesia) met. (Setting of Aristophanes' Knights.)

polemarch. One of the nine chief archons, chosen on an annual basis, of the Athenian state. Originally, the polemarch's province was the command of the city's military. That function wuld, though, pass to the strategoi with the arrival of selection by lot.

polis. A Greek city state (a city plus surrounding countryside). Athens was a polis consisting of the city of Athens itself, and the region of Attica. The polis was the principal political unit in archaic and classical Greece.

politeia. Citizenship, statehood, constitution. See also citizen.

polites. See citizen.

polupragmosune. "Energy," "industry." Or else an almost hubristic "meddlesomeness." See also apragmosune.

pornos/porne. Male or female "whore." In contrast to hetaira, a porne (female low-class prostitute) emphasized publicity (i.e., showing oneself prominently in public - ordinarily frowned upon), commodity (the word comes from verb "buy"), and anonymity (one didn't form an emotional attachment to a porne or pornos).

poneros. "Vulgar," "vile," termed of reproached used for, among other things, the non-aristocratic "new politicians" of the later 400s.

probouleusis. Probouleuseis (plural of probouleusis) were agenda items prepared by the Athenian boule for meetings of the assembly (ekklesia).

Probability (to eikos), argument from. Considered a specialty of sophists like Gorgias, arguing from probability (to eikos, "the likely") is to argue not from established facts, testimony, or the like, but from seemingly plausible claims, for instance, that "a person as tiny as I am couldn't have punched a guy that big so hard as to kill him," or that "an individual of my character and standing surely would never indulge in practices as infamous as those."

Argument from probability seems to have been a fixture in the courtroom speeches of ancient Athens, due partly, perhaps, to the relative unavailability and unreliability of physical evidence. Perhaps the most famous/notorious use of argument from probability was by the sophist-oligarch-logographer Antiphon. Accused of plotting to overthrow democracy in 411 BCE, Antiphon pleaded that a speech-writer-for-hire like him could hardly be expected to support oligarchy, a constitution hostile to the kinds of democratic jury trials that were the source of his livelihood. (As a logographer, he wrote speeches for others to use in court. Athens' court system was closely associated with its democracy.) Thucydides, evidently, admired the speech highly. The jury, however, didn't buy it. Antiphon was put to death.

Those are a defendant's refutations from probability, but positive assertions of guilt can be based on probability, too. Take Antiphon's First Tetralogy, a quartet of speeches meant to illustrate how to argue both sides of a homicide case. There, in the prosecutor's first speech, arguments from motive are explicitly arguments from probability: "Who is more likely (eikos) to have attacked [the victim] than a man who had already suffered cruelly at his hands. . .?" (1.4, Loeb trans.; cf. 1.9, "inferences from probability," tōn eikotōn). So, too, Aeschines' prosecution of Timarchus relies on the plausible and the probable when it adduces "common report" (phēmē, i.e., the talk of the town) as evidence for infamous practices on the defendant's part, a where-there's-smoke-there's-fire argument for stripping the the defendant of political rights on moral grounds. (It worked.)

Aristotle developed the theory of probable argument beyond the simple idea of plausible assertions and denials. In book 2 of the Rhetoric, he explores all sorts of rhetorical arguments, including enthymemes: rhetorical syllogisms with crowd appeal, i.e., based on the kinds of premises most folks would buy into. So, for instance, Antiphon's logographer defense (above) is an enthymeme. Logographers, as everybody knows, have a professional stake in a democratically organized judiciary. (Major premise based on the plausible.) Why, then, would a logographer like Antiphon want to sacrifice his livelihood by dissolving democracy? (Minor premise [Antiphon is an orator] and conclusion [Antiphon is no practicing oligarch] combined.)

prooimion ("proem"). The "introduction" or "preamble" to a speech, it often involves captatio benevolentiae.

prostates tou demou. "He who stands at

the head of the demos," "he who serves as protector

of the demos." The leader of the democracy, i.e., most

influential politician in the Athenian assembly during a given period.

(E.g., Pericles or Cleon.) Not a political office.

These prostatai (leaders-protectors of the people) were often viewed by anti-democrats

(e.g., the "Old Oligarch") as what could be termed "vulgar"

(poneroi, i.e., low-class, undeserving) demagogues. The prostates himself will want us to believe he leads the demos in the

sense of the entire citizenry; the opposition will want us to believe

the prostates has organized the rabble (demos as okhlos)

to his side.

protreptic. For our purposes it will suffice to understand "protreptic" as philosophical exhortation — discourse, in other words, aimed at winning over others to philosophy or to a particular school of philosophy. Much of what Socrates does in Plato's Gorgias can be described as protreptic.

psephisma. Plural psephismata; see decrees.

Pythian. = Apollo as god of the Delphic Oracle.

Pytho. = Delphi.

relativism. The idea that external reality is not uniform for everyone, but can vary depending on the individual perceiver and her/his point of view, etc.

rhetor. Speaker, orator, assembly politician.

rhetoric. (rhetorike tekhne, "the art appropriate to the rhetor.)

- The art of speaking and writing.

- The art of producing persuasive or effective discourse (logos).

- In Plato's Gorgias,

- according to Gorgias, skill at influencing people through speech

- according Socrates, a form of pandering, specifically, an experientially gained facility (not a skill or tekhnē involving theoretical knowledge) in verbal influencing

- According to Socrates in Plato's Phaedrus, "mind control" (psukhagōgia) through words.

- According to Aristotle, the study of the techniques of persuasion: not per se of implanting true knowlegde but resonable, plausible opinions. (Contrast Aristotelian dialectic.)

- In modern approaches to dialogue, discourse analysis, and the like, "social outreach forging connections, structuring reception, and, ultimately, shaping the 'realities' speakers/writers seek to share" (from a paper I'm working on).

See also sophistic.

Rhetoric of antirhetoric. The "rhetoric of antirhetoric" can be defined as the attempt to counteract the impact of another's words. That can involve alerting one's audience to attempts by one's opponent to use speech to win their favor. Or it can involve the attempt to spin one's opponent's words as some sort of verbal manipulation, whether it in fact is or is not.

rhetorical question. A statement posing as a question.

scholium. A marginal comment on a medieval manuscript of a classical literary work. Scholia often preserve important info. of various sorts.

skhema (plural skhemata). A "figure" of rhetoric, i.e., a verbal formulation combining sound and sense in striking ways: antithesis, epanaphora, etc. Compare the term gorgieia skhēmata, "Gorgianic figures," after the rhetorician best known for them.

sophist (pronounced "SAH-fist"). Greek sophistes. Prior to the later 400s BCE, a "wise man," one who stood out for sophia, wisdom or skill. By about 430, sophistes had come to refer to a professional (i.e., paid) teacher of subjects of interest to young men intending to enter public life. The term could carry negative connotations; to ordinary Athenians, it seems to have suggested a teacher of the art of verbal deception. See also sophistic.

sophistic. Sophistic is a noun referring to what the sophists did and taught (it is also an adjective, "sophistic reasoning"). A sophistry is an example of sophistic reasoning; the term can be used disparagingly to refer to an attractive, but bogus, argument. See also epideixis, eristic, rhetoric.

sophrosune. "Moderation," "self-control," "prudence," a slogan used by the later fifth-century oligarchs. Opposite of akolasia, "excess," which the oligarchs liked to think of as a democratic trait.

Sparta. In the classical period, the chief city in the Peloponnese (i.e., in southern Greece). A militarized, closed society, its constitution combined monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy.

Speech act theory. Click here.

Spin. "Spin" can be defined as the attempt to affect another's impressions of a thing, to make those impressions less or more favorable. That can involve a subtle shift in value judgments: "Well, you know, I wouldn't call that a defeat. I'd call it a learning experience." Or it can involve a radical rethinking: "Ill-considered boldness was counted as loyal manliness; prudent hesitation was held to be cowardice in disguise. . ." (Thucydides 3.82, trans. Woodruff).

stasis. Political faction, political disorder, revolution. Its opposite is harmonia ("harmony") or homonoia ("concord"). See also amnesty.

Stasis means literally a "standing." Thus in English it's used typically to mean a standing still or motionlessness. But as a term of politics in ancient Greece, stasis meant "taking a stand" such that one stood apart from another group. It connoted, therefore, at least in political contexts, a lack of consensus, indeed the presence of faction.

Though Greeks hardly expected everyone to agree all the time, the potential for disagreement to descend into factional strife was a very real and worrisome prospect. Factiona like could lead, as we shall see, to political murder, even massacre.

strategia. "Generalship." The board of ten strategoi, or "generals" - one from each of the ten Cleisthenic tribes, - were selected by vote. When in 487 lottery was decisively adopted for selection of the nine main archonships, the generals became the most important office at Athens - a kind of executive board with broad powers and duties. In peace, generals administered government; in war they commanded armies and ships. Pericles was a general for the better part of his political career.

strategos. "General," plural strategoi. See entry above.

sukophantes. "Sycophant,"

i.e., a judicial blackmailer. I'm a sycophant if I come up to you

and threaten to prosecute or sue you if you don't pay me off. Or

else I prosecute you not because I think you're guilty of

something, but I want to harm you judicially, perhaps becuse I've

been paid to do so.

To charge one with being

a sycophant in the later 400s is associated with the oligarchs - sort of a way to impugn the motives of someone poorer trying

to make his way up through the political ranks. (You often started

with law suits in the courts.) In 404, the first thing the oligarchs

did on gaining power was to get rid of persons they charged with

being sycophants. Our sources say this was the one thing they did

that was popular.

syllogism. A logical formula of Aristotle's devising, where two facts assumed to be true bear a relation to each other such that they imply a third fact necessarily true. Any given syllogism consists of a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion, for instance:

- MAJOR PREMISE. All human beings have souls.

- MINOR PREMISE. Socrates is a human being.

- CONCLUSION. Socrates has a soul.

If 1 and 2 above are true, then perforce so is 3. Syllogisms figure in enthymemes, for Aristotle, the basis of most persuasive speech.

symbouleutic. One of Aristotle's three genres of oratory, symbouleutic, "deliberative" or "political" oratory, was speech-making concerned with decisions to be made by a political body. According to Aristotle, symbouleutic concerns itself with advice (exhortation or warning) as to the expediency or imprudence of future action.

synoecism, sunoikismos. (sin-EE-sizm. sun "together" + oikos "household.")

The union of man and woman in matrimony to form a household; the

union of households to form a community; the union of communities

to form a polis.

Theseus, the mythical

king of Athens, is credited with using peitho to unite the demes (the villages) of Attica

to form the polis of Athens. Praxagora in Assemblywomen wants to remodel the houses of Athens into one big townhouse, a

kind of hyper-synoecism re-inaugurating the Athenian state as a

communalized society.

tekhne (plural tekhnai). In Greek, "skill" or "art." In Plato, tekhne has the very specific meaning of expertise informed systematic knowledge of a thing or a practice, especially its underlying principles — more a mastery of theory than practical familiarity. Thus for Socrates in Plato's Gorgias, medicine is a tekhne, cooking, empeiria, skill gained through doing, not thinking.

But the term tekhne also came to used for publications issued by Gorgias and others, textbooks of a sort in the "art" of rhetoric or whatever. The precise character of these tekhnai is in dispute. Some think that they consisted mostly of examples, or "demonstrations" (epideixeis), of various techniques of argument, expression, etc.

thalassocrat. One who "rules the sea" (e.g., fifth-century BCE Athenians).

Theoric Fund. It is said that the Theoric Fund (from theoria, "spectacle" or "show") was originally set up by Pericles to assist those too poor to afford admission to shows during theatrical festivals. In the 300s BCE, these moneys, basically, surplus revenue, became a more generalized form of state-sponsored welfare (construction projects, general distribution during religious festivals) and were protected by special laws. They became so closely associated with the state's general fund that administrators of the Theoric Fund for a while (350s-340s BCE) basically controlled the state's finances. This fund was considered so important that in the 340s, it was made an offense punishable by death to propose appropriating these moneys for purposes other than those intended by the Fund. On the one hand(See Demosthenes Third Olynthiac.)

thetes. Those forming the lowest economic and political class at Athens - mostly landless laborers. (The singular is thes.) Probably never the numerical majority at Athens, nevertheless they tended to benefit from the policies of radical democracy. The "thetic" class was the principal element among the paid oarsmen of the warships. A thes was by definition one who could not afford the weapons of a hoplite.

thopeia. Same as kolakeia.

topos. Or koinos topos, "common place" (plural koinoi topoi). Your Aristotle Rhetoric text translates the word as "topic." In Aristotle, it refers to a widely applicable mode or scheme of argument, a logical "template" from which many different arguments, enthymemes, can be constructed. Given a particular thesis one seeks to prove or disprove, one will select a proper topos to structure the right sort of proof or disproof.

Underlying Aristotle's understanding of the word seems to be its earlier use by sophists, for whom it perhaps meant commonly available, "prefabricated" or "ready-to-wear" verbal formulations (arguments, sentiments, topics, conceits etc.) that could be "plugged-in" to a discourse as needed. In that sense (one commonly used by critics today), a topos is like a cliché, only its appeal and effectiveness actually lie in its familiarity: it expresses a speaker's solidarity with attitudes endorsed by his/her audience.

That understanding of topos is not unrelated to Aristotle's use, as topoi in the Rhetoric clearly derive their plausibility in large part from the commonly accepted notions they deploy as arguments.

Put differently, speakers/writers use topoi to "push" this or that audience-response "button," depending on need. Compare the topoi of funeral eulogies nowadays:

- "He was a good husband and a good father

- "He rose high but never forgot where he came from"

- "He demanded much of his employees, but never more than he did of himself"

Topoi of ancient coutroom oratory:

- "My friends are your [the audience's] friends; my enemies, your enemies"

- "My opponent tells you he 'loves' you, but his actions speak otherwise"

- "Excuse my lack of polish. This is my first time before a court" (I.e., "Unlike my opponent, I'm just a regular Athenian who minds his own business")

Topoi of political oratory:

- "Others will tell you want you want to hear, will resort to flattery [etc.]; I will tell you what you need to hear"

- "Whose interests will you advance in your voting: those of your enemies abroad and of their lackeys here in the city, or your own?"

trierarch. A "trierarchy" is a form of liturgy. ("Trierarchy" is the office trierarch.) Viz., someone appointed by the state to fund construction and outfitting of a trireme (a warship).

tyranny. turannis. Rule by a turannos, "tyrant." Could mean various things: kingship, sovereignty or lordship, (more or less) absolute rule or despotism, extra-legal dictatorship (whether abusive or benign), abuse of power. Typically for our period and place, tyrants were viewed as rulers who had usurped legitimate power, which they held more or less by force, for instance, with the support of an armed guard. Tyranny didn't have to mean wholesale overthrow of a constitution, nor was it necessarily viewed as an arbitrary or evil exercise of power. In 500s BCE Athens, Peisistratus' power was based on the body guard the people had voted for him, but he seems to have ruled sort of from the background, without actually overthrowing the Solonian constitution. He is credited with a number of achievements generally treated as favorable to his and his city's reputation (e.g., establishment of dramatic festivals, temple construction on the Acropolis). Peisistratus' son Hippias, during the last years of his regime, is said to have ruled by violence. Typically, tyranny carried bad connotations. See also monarchy.

utopia. An ideal society of universal happiness and prosperity. Such societies are called "utopias" because they are typically imaginary "nowhere" places ("utopia" from Greek "no-place"). Sometimes the term used is "eutopia," a "good place." "Utopian" can sometimes suggest an unrealistic, misguided, or otherwise flawed idealism; compare dystopia.