Women in Greek

and Roman Theater

GRST 302-51

Tuesday/Thursday

1:30-2:45 PM

Sanders

Classroom 212

|

|

|

|

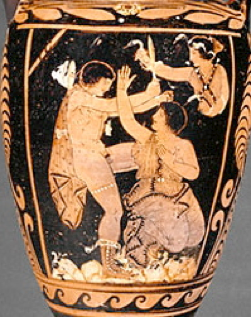

Paestan (S. Italian) red-figure amphora |

Mosaic of scene from Menander's Synaristosai "Women at Breakfast" |

Instructor:

John H. Starks, Jr.

Texts, Course Requirements, and Grade Distribution

Course Synopsis: Women, such as Clytemnestra, Medea, Helen, Hekabe/Hecuba,

Lysistrata, and Cleostrata, are among the most interesting characters developed

for the ancient stage. We will look at these women as entertaining and

stimulating visions of the feminine and unfeminine, as perceived by the

cultures that originally watched them and in our own day. This course

approaches Greek and Roman dramatic scripts, both tragic and comic, as vehicles

for presentation of social norms and anomalies at public festivals and for

general entertainment. As public works, these texts offer us a chance to

understand gender issues and social mores as presented by actors. We will also examine

and practice with ancient theater techniques to better understand the

presentation of females by actors, and we will discuss the venues and genres in

which women played female characters to examine the differences gender makes in

perception of character and in their real lives as working women. Students will

gain familiarity with these plays and characters through ample script analysis,

discussion, performance, feminist theoretical readings, and oral and written

presentations of original work.

This course must begin with Aeschylus’ Oresteia as a powerful commentary on early classical

Athenian impressions of women, motherhood and the feminine/masculine dichotomy

presented before a public audience. Several of Euripides’ war plays (Andromache,

Trojan Women, Hecuba) focused on the

defeated Trojan women address both standard societal observations on women in

crisis and a developing dramatic intensity in Euripides’ female roles. Excerpts

from Medea show that Euripides

actively thought about his presentation of the feminine and unfeminine in his

dramatic constructions and give voice to the foreign woman in a Greek context.

The rescue drama Ion presents rape as

a serious and complex social offense against women, but also shows a growing

attraction for dramatic resolution found in reconciliation and restoration of

domestic peace.

Aristophanes’ “women” plays (Lysistrata,

Thesmophoriazousai, Ekklesiazousai),

while resting firmly on the comic appeal of offering male stereotypes of women,

also raise new social issues regarding the role women played in Athenian civic

and religious life, and address Euripides’ approach to presentation of the

tragic woman. Three of Plautus’ “darker” social comedies (Bacchides, Casina,

Truculentus) show a continuing

fascination with women at the center of dramatic structure and offer

significant voice to women’s comments on their public and domestic roles in

Hellenistic Greek society, and sometimes glimpses of their place in Roman

society. A selection of Hellenistic and late Greek mime scripts will help

further develop this picture of women’s dual lives and indicate some of the few

roles actually played by actresses on Greek and Roman stages. We will end with

Seneca’s Medea and Trojan Women to study his differing dramatic techniques, philosophical

concerns and Roman imperial impressions regarding tragic Greek women.

|

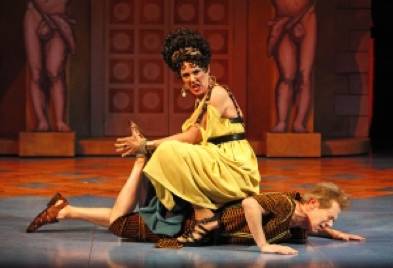

Domina oppresses Hysterium – Stratford

Shakespeare Festival 2009 Martha Graham dancing the title role in

her Clytemnestra 1960 |