Persuasion in Ancient Greece

Andrew Scholtz, Instructor

Course Readings. . .

Plato Gorgias

GORGIASBy Plato

Translated by Benjamin Jowett (revised and with notes by A. Scholtz)

PERSONS OF THE DIALOGUE:

- Callicles (an up and coming politician)

- Socrates (a philosopher)

- Chaerephon (Socrates' good friend)

- Gorgias (a sophist, or professional teacher to young men)

- Polus (another sophist)

SCENE: Athens, Greece, 427 BCE. The house of Callicles, where Gorgias, a foreigner visiting Athens on embassy, has just been lecturing on, and demonstrating, the art of rhetoric. Indeed, while in Athens, he has been enthralling Athenians with the power and novelty of his eloquence, and is in fact a renowned author and teacher of rhetoric, besides being a skilled speaker. Socrates and his good friend Chaerephon did not, however, make it on time for the show, and have only just arrived as the dialogue starts.

---Plato's text begins here---

[447a] CALLICLES: The wise man, as the proverb says, is late for a fray, but not for a feast.

SOCRATES: And are we late for a feast?

CALLICLES: Yes, and a delightful feast. For Gorgias has just been exhibiting to us many fine things.

SOCRATES: It is not my fault, Callicles; our friend Chaerephon is to blame. For he would keep us loitering in the Agora.*

* The agora was the marketplace and political and judicial hub of Athens. As such it was also a hangout, particularly for the city's wealthy youth. [All notes, marked with asterisk (*), by AS.]

[447b] CHAEREPHON: Never mind, Socrates; the misfortune of which I have been the cause I will also repair. For Gorgias is a friend of mine, and I will make him give the exhibition again either now, or, if you prefer, at some other time.

CALLICLES: What is the matter, Chaerephon — does Socrates want to hear Gorgias?

CHAEREPHON: Yes, that was our intention in coming.

CALLICLES: Come into my house, then. For Gorgias is staying with me, and he will exhibit to you.

SOCRATES: Very good, Callicles. But will he answer our questions? [447c] For I want to hear from him what is the nature of his art,* and what it is which he professes and teaches; he may, as you, Chaerephon, suggest, put off the exhibition to some other time.

* Greek tekhnē.

CALLICLES: There is nothing like asking him, Socrates. And indeed to answer questions is a part of his exhibition, for he was saying only just now, that any one in my house might put any question to him, and that he would answer.

SOCRATES: How fortunate! Will you ask him, Chaerephon?

CHAEREPHON: What will I ask him?

[447d] SOCRATES: Ask him who he is.

CHAEREPHON: What do you mean?

SOCRATES: I mean the kind of question that would elicit from him, if he had been a crafter of shoes, the answer that he is a shoemaker. Do you understand?

CHAEREPHON: I understand, and will ask him: Tell me, Gorgias, is our friend Callicles right in saying that you undertake to answer any questions which you are asked?

[448a] GORGIAS: Quite right, Chaerephon: I was saying as much only just now. And I may add, that many years have elapsed since any one has asked me a new one.

CHAEREPHON: Then you must be very ready, Gorgias.

GORGIAS: Of that, Chaerephon, you can make trial.

POLUS: Yes, indeed, and if you like, Chaerephon, you may make trial of me too, for I think that Gorgias, who has been talking a long time, is tired.

CHAEREPHON: And do you, Polus, think that you can answer better than Gorgias?

[448b] POLUS: What does that matter if I answer well enough for you?

CHAEREPHON: Not at all, and you will answer if you like.

POLUS: Ask.

CHAEREPHON: My question is this: If Gorgias had the skill of his brother Herodicus, what should we call him? Should we not call him what we call his brother?

POLUS: Certainly.

CHAEREPHON: Then we would be right in calling him a physician?

POLUS: Yes.

CHAEREPHON: And if he had the skill of Aristophon the son of Aglaophon, or of his brother Polygnotus, what should we call him?

[448c] POLUS: Clearly, a painter.

CHAEREPHON: But now what will we call Gorgias — what is the art in which he is skilled?

POLUS: O Chaerephon, there are many arts among humankind which are experiential, and have their origin in experience, for experience makes the days of human beings to proceed according to art, and inexperience according to chance, and different persons in different ways are proficient in different arts, and the best persons in the best arts. And our friend Gorgias is one of the best, and the art in which he is proficient is the noblest.

[448d] SOCRATES: Polus has been taught how to make a capital speech,* Gorgias. But he is not fulfilling the promise which he made to Chaerephon.

*In Greek, logos: "speech," "oration," "argument," "discourse" generally. From Greek logos come words like "logic" (logikē tekhnē, the art of fashioning well-reasoned arguments) and "psychology" (reasoned discourse pertaining to soul or mind, psukhē).

GORGIAS: What do you mean, Socrates?

SOCRATES: I mean that he has not exactly answered the question which he was asked.

GORGIAS: Then why not ask him yourself?

SOCRATES: But I would much rather ask you, if you are disposed to answer. For I see, from the few words which Polus has uttered, that he has attended more to the art which is called rhetoric than to dialectic.*

* The Greek for "rhetoric" is rhētorikē, the "art (tekhnē) of speaking." The Greek for "dialectic," (the art of analyzing and exploring a question through reasoned argument — Socrates means to contrast that with rhetoric) is dialektikē.

[448e] POLUS: What makes you say so, Socrates?

SOCRATES: Because, Polus, when Chaerephon asked you what was the art which Gorgias knows, you praised it as if you were answering someone who found fault with it, but you never said what the art was.

POLUS: Why, did I not say that it was the noblest of arts?

SOCRATES: Yes, indeed, but that was no answer to the question: nobody asked what was the quality, but what was the nature, of the art, and by what name we were to describe Gorgias. [449a] And I would still beg you briefly and clearly, as you answered Chaerephon when he asked you at first, to say what this art is, and what we ought to call Gorgias. Or rather, Gorgias, let me turn to you, and ask the same question: What are we to call you, and what is the art which you profess?

GORGIAS: Rhetoric,* Socrates, is my art.

* rhētorikē.

SOCRATES: Then I am to call you a rhetorician?*

* Greek rhētōr: "speaker," "orator."

GORGIAS: Yes, Socrates, and a good one too, if you would call me that which, in Homeric language, "I boast myself to be."

SOCRATES: I would wish to do so.

GORGIAS: Then pray do.

[449b] SOCRATES: And are we to say that you are able to make other men rhetoricians?

GORGIAS: Yes, that is exactly what I profess to make them, not only at Athens, but in all places.

SOCRATES: And will you continue to ask and answer questions, Gorgias, as we are at present doing, and reserve for another occasion the longer mode of speech* which Polus was attempting? Will you keep your promise, and answer briefly the questions which are asked of you?

* logos.

GORGIAS: Some answers, Socrates, are of necessity longer; [449c] but I will do my best to make them as short as possible. For a part of my profession is that I can be as brief as any one.

SOCRATES: That is what is wanted, Gorgias; exhibit the shorter method now, and the longer one at some other time.

GORGIAS: Well, I will. And you will certainly say that you never heard anyone use fewer words.

SOCRATES: Very good then. As you profess to be a rhetorician, and a crafter of rhetoricians,*

* That is, a teacher of rhetoric.

let me ask you, [449d] with what is rhetoric concerned? I might ask with what is weaving concerned, and you would reply, would you not, with the making of garments?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And music is concerned with the composition of melodies?

GORGIAS: It is.

SOCRATES: By Hera,* Gorgias, I admire the surpassing brevity of your answers!

* Hera was one of the ancient Greek gods. Wife of Zeus, she was the chief female god.

GORGIAS: Yes, Socrates, I do think myself good at that.

SOCRATES: I am glad to hear it; answer me in like manner about rhetoric. With what is rhetoric concerned?

[449e] GORGIAS: With discourse.*

* logos.

SOCRATES: What sort of discourse, Gorgias? Such discourse as would teach the sick under what treatment they might get well?

GORGIAS: No.

SOCRATES: Then rhetoric does not deal with all kinds of discourse?

GORGIAS: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: And yet rhetoric makes men able to speak?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And to understand that about which they speak?

GORGIAS: Of course.

[450a] SOCRATES: But does not the art of medicine, which we were just now mentioning, also make men able to understand and speak about the sick?

GORGIAS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Then medicine also deals with discourse?*

* Medicine deals with logos not simply in the sense of "words" but in the sense of "knowledge and inquiry expressed through reasoned discourse." Biology is "reasoned discourse" (logos) addressing the life (bios) sciences. All disciplines have a discourse (logos) appropriate to them, but Gorgias wants to focus just on the words (logos) part, to treat that as its own, specialized area of study: rhetoric.

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: With discourse concerning diseases?

GORGIAS: Just so.

SOCRATES: And does not gymnastic also deal with discourse concerning the good or evil condition of the body?

GORGIAS: Very true.

[450b] SOCRATES: And the same, Gorgias, is true of the other arts: all of them deal with discourse concerning the subjects with which they severally have to do.

GORGIAS: Clearly.

SOCRATES: Then why, if you call rhetoric the art which deals with discourse, and all the other arts deal with discourse, do you not also call those other arts, arts of rhetoric?

GORGIAS: Because, Socrates, the knowledge of the other arts has only to do with some sort of external action, as of the hand. But there is no such action of the hand in rhetoric, which works and takes effect only through the medium of discourse. [450c] I am, therefore, justified in saying that rhetoric deals with discourse.

SOCRATES: I am not sure whether I entirely understand you, but I dare say I will soon know better. Please answer me a question: Would you admit that there are arts?*

* "Arts" translates Greek tekhnai, plural of tekhnē, "art," "skill."

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: As to the arts generally, they are for the most part concerned with doing, and require little or no speaking; in painting, and statuary, and many other arts, the work may proceed in silence; [450d] and of such arts I suppose you would say that they do not fall within the realm of rhetoric.

GORGIAS: You perfectly understand my meaning, Socrates.

SOCRATES: But there are other arts which work wholly through the medium of language, and require either no action or very little, as, for example, the arts of mathematics, of calculation, of geometry, and of playing checkers; in some of these there is pretty nearly as much speech involved as action, but in most of them the speech element is greater — [450e] they depend wholly on words for their efficacy and power, and I take your meaning to be that rhetoric is an art of this latter sort?

GORGIAS: Exactly.

SOCRATES: And yet I do not believe that you really mean to call any of these arts rhetoric, although the precise expression which you used was that rhetoric is an art which works and takes effect only through the medium of words. And if someone wanted to pick an argument with you, he might say "And so, Gorgias, you call mathematics rhetoric." But I do not think that you really call mathematics rhetoric any more than geometry would be so called by you.

[451a] GORGIAS: You are quite right, Socrates, in your apprehension of my meaning.

SOCRATES: Well, then, let me now have the rest of my answer. Seeing that rhetoric is one of those arts which works mainly by the use of words, and there are other arts which also use words, tell me what is that quality in words with which rhetoric is concerned. Suppose that a person asks me about some of the arts which I was mentioning just now; he might say, "Socrates, what is mathematics?" [451b] and I would reply to him, as you replied to me, that mathematics is one of those arts which take effect through words. And then he would proceed to ask: "Words about what?" and I would reply, "Words about odd and even numbers, and how many there are of each." And if he asked again: "What is the art of calculation?" I would say, "That also is one of the arts which is concerned wholly with words." And if he further said, [450c] "Concerned with what?" I would say, like the clerks in the assembly, "as aforesaid" of mathematics, but with a difference, the difference being that the art of calculation considers not only the quantities of odd and even numbers, but also their numerical relations to themselves and to one another. And suppose, again, were I to say that astronomy is only words — he would ask, "Words about what, Socrates?" and I would answer that astronomy tells us about the motions of the stars and sun and moon, and their relative swiftness.

GORGIAS: You would be quite right, Socrates.

[451d] SOCRATES: And now let us have from you, Gorgias, the truth about rhetoric, which you surely would admit to be one of those arts which act always and fulfill all their ends through the medium of words?*

* "Words" = logos.

GORGIAS: True.

SOCRATES: Words which do what? I would ask. To what class of things do the words which rhetoric uses relate?

GORGIAS: To the greatest, Socrates, and the best of human things.

SOCRATES: That again, Gorgias is ambiguous; I am still in the dark. For which are the greatest and best of human things? [451e] I dare say that you have heard men singing at drinking parties* the old drinking song, in which the singers enumerate the goods of life, first health, beauty next, thirdly, as the writer of the song says, wealth honestly obtained.

* The sumposion or "drinking party" (the Greek word gives us "symposium") involved eating followed by moderate to heavy drinking. It could also involve singing, story telling, and clever, sometimes philosophical, conversation.

GORGIAS: Yes, I know the song, but what is your drift?

[452a] SOCRATES: I mean to say, that the producers of those things which the author of the song praises, that is to say, the physician, the physical trainer, the money-maker, will at once come to you, and first the physician will say: "O Socrates, Gorgias is deceiving you, for my art is concerned with the greatest good of human beings and not his." And when I ask, "Who are you?" he will reply, "I am a physician." "What do you mean?" I will say. "Do you mean that your art produces the greatest good?" "Certainly," he will answer, "for is not health the greatest good? What greater good can human beings have, Socrates?" [452b] And after him the trainer will come and say, "I too, Socrates, will be greatly surprised if Gorgias can show more good of his art than I can show of mine." To him again I will say, "Who are you, honest friend, and what is your business?" "I am a trainer," he will reply, "and my business is to make men beautiful and strong in body." When I have done with the trainer, there arrives the money-maker, and he, as I expect, will utterly despise them all. [452c] "Consider Socrates," he will say, "whether Gorgias or any one else can produce any greater good than wealth." "Well," you and I say to him, "and are you a creator of wealth?" "Yes," he replies. "And who are you?" "A money-maker." "And do you consider wealth to be the greatest good of man?" "Of course," will be his reply. And we will respond: "Yes. But our friend Gorgias contends that his art produces a greater good than yours." And then he will be sure to go on and ask, "What good? Let Gorgias answer." [452d] Now, I want you, Gorgias, to imagine that this question is asked of you by them and by me: "What is that which, as you say, is the greatest good of man, and of which you are the creator?" Answer us.

GORGIAS: That good, Socrates, which is truly the greatest, being that which gives to people freedom in their own persons, and to individuals the power of ruling over others in their several city states.*

* In what follows, "city" translates the Greek word polis in the sense of "city state," that is, a sovereign political entity centered around a single urban center like Athens. The territory, called "Attica" ("Shorełand"), controlled by Athens was about the size of the state of Rhode Island. Singapore could be said to be a modern version of a city state. Polis, the root of the word "politics," thus can mean:SOCRATES: And what would you consider this to be?

- "City" in the sense of urban center

- "City state" in the above sense

- "State" in the abstract sense of the political structures governing a territory and its people — "the State"

- A city state's citizens as a collective

- Note that ancient Greece was not yet a single, unified country in the political sense. An independent and more or less unified Greek state would not be recognized internationally until 1832 CE. It was, rather, a collection of poleis ("city states") and larger-scale ethnic "leagues" or collectives of Greeks with a shared sense of identity.

[452e] GORGIAS: It's the ability to use words to persuade the judges in the courts,* or the council members in the council, or the citizens in the assembly, or at any other political meeting. If you have the power of uttering this word, you will have the physician as your slave, and the trainer as your slave, and the money-maker of whom you talk will be found to gather treasures, not for himself, but for you who are able to speak and to persuade the multitude.

* "words to persuade" — the Greek uses a form of the noun logos for "words" and a form of the verb peithō for "to persuade."

SOCRATES: Now I think, Gorgias, that you have very accurately explained what you conceive to be the art of rhetoric. [453a] And you mean to say, if I am not mistaken, that rhetoric is the crafter of persuasion,* having this and no other business, and that this is her crown and end. Do you know any other effect of rhetoric over and above that of producing persuasion?

* "Crafter of persuasion" — here, "persuasion" translates a noun form, peithō, similar in meaning to the verb peithō "persuade," but accented differently (noun pay-THŌ, verb PAY-thō).

GORGIAS: No: the definition seems to me very fair, Socrates. For persuasion is the chief end of rhetoric.

SOCRATES: Then hear me, Gorgias, for I am quite sure that [453b] if there ever was anyone who entered on the discussion of a matter because he wants to know the truth, I am such a one, and I would say the same of you.

GORGIAS: What is coming, Socrates?

SOCRATES: I will tell you. I am very well aware that I do not know what, according to you, is the exact nature, or what are the topics, of that persuasion about which you speak, and which is given by rhetoric. I do, though, have a suspicion about both its nature and its topics. And I am going to ask: What is this power of persuasion which is given by rhetoric, and about what? But why, if I have a suspicion, do I ask instead of telling you? Not for your sake, but in order that the argument may proceed in such a manner as is most likely to set forth the truth. And I would have you observe that I am right in asking this further question: If I asked, "What sort of a painter is Zeuxis?" and you said, "The painter of figures," would I not be right in asking, "What kind of figures, and where do you find them?"

GORGIAS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And the reason for asking this second question would be, that there are other painters besides, who paint many other figures?

GORGIAS: True.

SOCRATES: But if there had been no one but Zeuxis who painted them, then would you have answered very well.

GORGIAS: Quite so.

SOCRATES: Now I want to know about rhetoric in the same way. Is rhetoric the only art which brings persuasion, or do other arts have the same effect? I mean to say, does the one who teaches anything persuade people of that which he teaches, or not?

GORGIAS: He persuades, Socrates, there can be no mistake about that.

SOCRATES: Again, if we take the arts of which we were just now speaking, do not mathematics and the mathematicians teach us the properties of number?

GORGIAS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And therefore persuade us of them?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: Then mathematics as well as rhetoric is a crafter of persuasion?

GORGIAS: Clearly.

SOCRATES: And if any one asks us what sort of persuasion, and about what, we will answer, persuasion which teaches [454a] the quantity of odd and even. And we will be able to show that all the other arts of which we were just now speaking are makers of persuasion, and of what sort, and about what.

GORGIAS: Very true.

SOCRATES: Then rhetoric is not the only crafter of persuasion.

GORGIAS: True.

SOCRATES: Seeing, then, that not only rhetoric works by persuasion, but that other arts do the same, as in the case of the painter, it's fair to ask: Of what kind of persuasion is rhetoric the crafter, and about what? [454b] Is not that a fair way of putting the question?

GORGIAS: I think so.

SOCRATES: Then, if you approve the question, Gorgias, what is the answer?

GORGIAS: I answer, Socrates, that rhetoric is the art of persuasion in courts of law and other assemblies, as I was just now saying, and about the just and unjust.

SOCRATES: And that, Gorgias, was what I was suspecting to be your notion. Yet I would not have you wonder if just now I asked you a seemingly plain question. For I ask not in order to confute you, [454c] but, as I was saying, so that the argument may proceed consecutively, and that we may not get the habit of anticipating and suspecting the meaning of one another"s words. I would have you develop your own views in your own way, whatever may be your hypothesis.

GORGIAS: I think that you are quite right, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Then let me raise another question. Is there such a thing as "having learned"?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And is there also "having believed"?

[454d] GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And is "having learned" the same as "having believed," and are learning and belief the same things?

GORGIAS: In my judgment, Socrates, they are not the same.

SOCRATES: And your judgment is right, as you'll see from the following. If a person were to say to you, "Is there, Gorgias, a false belief* as well as true?" you would reply, if I am not mistaken, that there is.

* The Greek for belief is pistis, a noun related to persuasion (peithō). Persuading and believing are closely related activities.

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: Well, but is there false knowledge as well as true?

GORGIAS: No.

SOCRATES: No, indeed, and this again proves that knowledge and belief differ.

GORGIAS: Very true.

[454e] SOCRATES: And yet those who have learned as well as those who have believed are persuaded?

GORGIAS: Just so.

SOCRATES: Shall we then assume two sorts of persuasion, one which is the source of belief without knowledge, as the other is of knowledge?

GORGIAS: By all means.

SOCRATES: And which sort of persuasion does rhetoric create in courts of law and other assemblies about the just and unjust? The sort of persuasion which gives belief without knowledge, or that which gives knowledge?

GORGIAS: Clearly, Socrates, that which only gives belief.

[455a] SOCRATES: Then rhetoric, it seems, is the crafter of a persuasion which creates belief about the just and unjust, but gives no instruction about them?

GORGIAS: True.

SOCRATES: And the rhetorician does not instruct the courts of law or other assemblies about things just and unjust. Rather, he creates belief about them. For no one can be supposed to instruct such a vast multitude about such high matters in a short time.

GORGIAS: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: Come, then, and let us see what we really mean about rhetoric. For I do not know what my own meaning is as yet. [455b] When the assembly meets to elect a physician or a shipwright or any other craftsman, will the rhetorician be consulted? Surely not. For at every election the one who ought to be chosen is the one who is most skilled. And, again, when walls have to be built or harbors or docks to be constructed, not the rhetorician but the master workman will advise. Or when generals have to be chosen and an order of battle arranged, or a position taken, [455c] then the military will advise and not the rhetoricians. What do you say, Gorgias? Since you profess to be a rhetorician and a crafter of rhetoricians, I cannot do better than learn the nature of your art from you. And here, let me assure you that I have your interest in view as well as my own. For likely enough some one or other of the young men present might desire to become your pupil, and in fact I see some, and a good many too, who have this wish, but they would be too modest to question you. [455d] And therefore when you are interrogated by me, I would have you imagine that you are interrogated by them. "What is the use of coming to you, Gorgias?" they will say — "about what will you teach us to advise the city? About the just and unjust only, or about those other things also which Socrates has just mentioned?" How will you answer them?

GORGIAS: I will try, then, to reveal the whole nature of rhetoric. [455e] You must have heard, I think, that the docks and the walls of the Athenians and the plan of the harbor were devised in accordance with the advice, partly of Themistocles, and partly of Pericles, and not at the suggestion of the builders.

SOCRATES: Such is the tradition, Gorgias, about Themistocles. And I myself heard the speech of Pericles when he advised us about the middle wall.*

* A protective wall guarding the road from the city of Athens to its harbor.

[456a] GORGIAS: And you will observe, Socrates, that when a decision has to be given in such matters the rhetoricians are the advisers; they are the men who win their point.

SOCRATES: I had that in my admiring mind, Gorgias, when I asked what is the nature of rhetoric, which, when I look at the matter in this way, always appears to me to be a marvel of greatness.

GORGIAS: A marvel, indeed, Socrates, if you only knew how rhetoric comprehends and holds under its sway all the inferior arts. [456b] Let me offer you a striking example of this. On several occasions I have been with my brother Herodicus or some other physician to see one of his patients, who would not allow the physician to give him medicine, or apply the knife or hot iron to him. And I have persuaded the patient to do for me what he would not do for the physician, just by the use of rhetoric. And I say that if a rhetorician and a physician were to go to any city, and had there to argue in the popular assembly or any other political body as to which of them should be elected state-physician, [456c] the physician would have no chance. But whoever could speak would be chosen if he wished, and in a contest with a man of any other profession, the rhetorician more than any one would have the power of getting himself chosen. For he can speak more persuasively to the multitude than any of them, and on any subject. Such is the nature and power of the art of rhetoric. [456d] And yet, Socrates, rhetoric should be used like any other competitive art, though not against everybody. The rhetorician ought not to abuse his strength any more than a boxer or pancratiast*

* A sport combining boxing, wrestling, kicking, and all other kinds of hand-to-hand fighting, except no biting or eye-gouging.

or other master of martial arts, just because he has powers which are more than a match either for friend or foe. He ought not, therefore, to strike, stab, or slay his friends. Suppose a man to have been trained in the gymnasium and to be a skilful boxer. He, in the fullness of his strength, goes and strikes his father or mother or one of his familiars or friends. [456e] But that is no reason why the trainers or sword-masters should be held in detestation or banished from the city; surely not. For they taught their art for a good purpose, to be used against enemies and evil-doers, [457a] in self defence, not in aggression, whereas others have perverted their instructions, and turned to a bad use their own strength and skill. But not on this account are the teachers bad, nor is the art in fault, or bad in itself. I would rather say that those who make a bad use of the art are to blame.

And the same argument holds good of rhetoric. For the rhetorician can speak against all men and upon any subject, in short, he can persuade the multitude better than any other man of anything which he pleases. [457b] But he should not therefore seek to defraud the physician or any other artist of his reputation merely because he has the power. He ought instead to use rhetoric fairly, as he would also use his athletic powers. And if after having become a rhetorician he makes a bad use of his strength and skill, his instructor surely ought not on that account to be held in detestation or banished. [457c] For he was intended by his teacher to make a good use of his instructions, but he abuses them. And therefore he is the person who ought to be held in detestation, banished, and put to death, and not his instructor.

SOCRATES: You, Gorgias, like myself, have had great experience in debating, and you must have observed, I think, [457d] that debates do not always terminate in mutual edification, or in the definition by either party of the subjects which they are discussing. But disagreements are apt to arise: somebody says that another has not spoken truly or clearly. And then they get into a passion and begin to quarrel, both parties conceiving that their opponents are arguing from personal feeling only and jealousy, not from any interest in the question at issue. And sometimes they will go on abusing one another until the company at last is quite upset with themselves for ever having listened to such fellows.

[457e] Why do I say this? Why, because I cannot help feeling that you are now saying what is not quite consistent or in accord with what you were saying at first about rhetoric. And I am afraid to point this out to you, in case you think that I have some animosity against you, and that I speak, not for the sake of discovering the truth, but to attack you. [458a] Now, if you are one of my sort, I would like to cross-examine you, but if not I will let you alone. "And what is my sort?" you will ask. I am one of those who are very willing to be refuted if I say anything which is not true, and very willing to prove any one else wrong who says what is not true, and quite as ready to be refuted as to refute. For I hold that this is the greater gain of the two, just as the gain of being cured of a very great evil is greater than that of curing someone else. For I imagine that there is no evil which a man can endure so great as an erroneous opinion about [458b] the matters of which we are speaking. And if you claim to be one of my sort, let us have the discussion out, but if you would rather have done, no matter; let us make an end of it.

GORGIAS: I would say, Socrates, that I am quite the man whom you have in mind. But, perhaps, we ought to consider the audience, for, before you came, I had already given a long exhibition, [458c] and if we proceed, the argument may run on to a great length. And therefore I think that we should consider whether we may not be detaining some part of the company when they are wanting to do something else.

CHAEREPHON: You hear the audience cheering, Gorgias and Socrates, which shows their desire to listen to you. As for myself, heaven forbid that I should have any business on hand that would take me away from a discussion so interesting and so ably managed.

[458d] CALLICLES: By the gods, Chaerephon, although I have been present at many discussions, I doubt whether I was ever so much delighted before, and therefore if you go on discoursing all day I will be the better pleased.

SOCRATES: I may truly say, Callicles, that I am willing, if Gorgias is.

GORGIAS: After all this, Socrates, I would be disgraced if I refused, especially as I have promised to answer all comers. [458e] In accordance with the wishes of the company, then, do you begin, and ask of me any question which you like.

SOCRATES: Let me tell you then, Gorgias, what surprises me in your words. Though I dare say that you may be right, and I may have misunderstood your meaning. Do you say that you can make any man, who will learn from you, a rhetorician?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: Do you mean that you will teach him to gain the ears of the multitude on any subject, [459a] and this not by instruction but by persuasion?

GORGIAS: Quite so.

SOCRATES: You were saying, in fact, that the rhetorician will have greater powers of persuasion than the physician even in a matter of health, right?

GORGIAS: Yes, with the multitude, that is.

SOCRATES: You mean to say, with the ignorant. For with those who know, he cannot be supposed to have greater powers of persuasion.*

* Crucial point: knowledge of the subject matter at hand inoculates us against the efforts of others to sway us any way they want. It sort of suggests that rhetoric can operate as a kind of deception, or at least partly derives its power from the ignorance of the audience. The same idea is developed in surprising ways in the Gorgias readings (works written by the historical Gorgias).

GORGIAS: Very true.

SOCRATES: But if he is to have more power of persuasion than the physician, he will have greater power than one who knows?

GORGIAS: Certainly.

[459b] SOCRATES: Although he is not a physician, right?

GORGIAS: Right.

SOCRATES: And whoever is not a physician must, obviously, be ignorant of what the physician knows.

GORGIAS: Clearly.

SOCRATES: So, when the rhetorician is more persuasive than the physician, it's a case of the ignorant being more persuasive with the ignorant — more persuasive than the one who has knowledge. Is that not the inference?

GORGIAS: In that case, yes.

SOCRATES: And the same holds of the relation of rhetoric to all the other arts. The rhetorician need not know the truth about things. [459c] He has only to discover some way of persuading the ignorant that he has more knowledge than those who know.

GORGIAS: Yes, Socrates, and is not this a great comfort? Not to have learned the other arts, but the art of rhetoric only, and yet to be in no way inferior to the professors of those other arts?

SOCRATES: Whether the rhetorician is or is not inferior on this account is a question which we will hereafter examine if the inquiry is likely to be of any service to us. [459d] But I would rather begin by asking whether the rhetorician is or is not ignorant of the just and unjust, of the base and the beautiful,*

* "Beautiful," which here translates kalon, is the basic meaning of that word. The "call-" in "calligraphy" or "Callicles" comes from the same root. But kalon could also mean "good" or "fine" or "honorable": honor is a beautiful thing. To the ancient Greek way of thinking, honor and beauty are much the same.

of good and evil, to the same degree that he is of medicine and the other arts. I mean, does he really know anything of what is good and evil, base or beautiful, just or unjust in them? Or has he only a way with the ignorant, persuading them that he is to be esteemed for knowing more about these things than someone else who knows? [459e] For remember: he does not know. Or must the pupil know these things and come to you knowing them before he can acquire the art of rhetoric? If he is ignorant, you who are the teacher of rhetoric will not teach him those things: it is not your business. But you will make him seem to the multitude to know them, when he does not know them. And seem to be a good man, when he is not.* Or will you be unable to teach him rhetoric at all, unless he knows the truth of these things first? What is to be said about all this? [460a] By Zeus, Gorgias, I wish that you would reveal to me the power of rhetoric, as you were saying you would.

* This idea that the art of persuasion — Socrates Gorgias are calling it rhetoric — is concerned with managing appearances is crucial. It will come back again and again in this course.

GORGIAS: Well, Socrates, I suppose that if the pupil does chance not to know them, he will have to learn these things from me as well.

SOCRATES: Say no more, for there you are right. And so whomever you make a rhetorician must either know the nature of the just and unjust already, or he must be taught those things by you.

[460b] GORGIAS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: Well, and is not whoever has learned carpentering a carpenter?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And whoever has learned music a musician?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And is whoever has learned medicine a physician, in like manner? Whoever has learned anything whatever is that which his knowledge makes him.

GORGIAS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And in the same way, is he just, who has learned what is just?

GORGIAS: To be sure.

SOCRATES: And whoever is just may be supposed to do what is just?

GORGIAS: Yes.

[460c] SOCRATES: And must not the rhetorician be a just man, and must not just man always desire to do what is just?

GORGIAS: That is clearly the inference.

SOCRATES: Surely, then, the just man will never consent to do injustice?

GORGIAS: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: And according to the argument, the rhetorician must be a just man?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And will therefore never be willing to do injustice?

GORGIAS: Clearly not.

SOCRATES: But do you remember saying just now that the trainer is not to be accused or banished if the boxer makes a wrong use of his boxer's art. [460d] And in like manner, if the rhetorician makes a bad and unjust use of his rhetoric, that is not to be laid to the charge of his teacher, who is not to be banished, but the wrongdoer himself who made a bad use of his rhetoric — he is to be banished — was that not said?

GORGIAS: Yes, it was.

[460e] SOCRATES: But now we are affirming that the aforesaid rhetorician will never have done injustice at all, true?

GORGIAS: True.

SOCRATES: And at the very outset, Gorgias, it was said that rhetoric dealt with discourse, not about odd and even number (mathematics deals with that), but about just and unjust? Was that not said?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: I was thinking at the time, when I heard you saying so, that rhetoric, which is always discoursing about justice, could not possibly be an unjust thing. But when you added, shortly afterwards, that the rhetorician might make a bad use of rhetoric [461a] I noted with surprise the inconsistency into which you had fallen. And I said that if you thought, as I did, that there was a gain in being refuted, there would be an advantage in going on with the question, but if not, I would leave off. And in the course of our investigations, as you will see yourself, the rhetorician has been acknowledged to be incapable of making an unjust use of rhetoric, or of consenting to do injustice. [461b] By the dog,* Gorgias, there will be a great deal of discussion, before we get at the truth of all this.

* Socrates was fond of the expression, "By the dog." We learn later that this dog is the Egyptian god Anubis, possibly a jackal or a species of wolf.

POLUS: And do even you, Socrates, seriously believe what you are now saying about rhetoric? What! Because Gorgias was ashamed to deny that the rhetorician knew the just and the beautiful and the good, and admitted that, if any one ignorant of those subjects came to him, he could teach them those subjects, and then out of this admission there arose a contradiction — [461c] the thing which you dearly love, and to which not he, but you, brought the argument by such questions — do you seriously believe that there is any truth in all this? For will any one ever acknowledge that he does not know, or cannot teach, the nature of justice? The truth is that it is truly boorish to bring the argument to such a pass.

SOCRATES: O most excellent Polus,*

* Note how Socrates plays with Polus. Polus, whose name means "colt," is young, impetuous, and ambitious. Socrates' "O most excellent Polus" treats the young man as an outstanding figure. But in what follows, Socrates is patronizing toward Polus, who is being more than a little rude. Polus is, like Gorgias, a teacher of rhetoric.

the reason why we provide ourselves with friends and children is that when we get old and stumble, a younger generation may be at hand to set us on our legs again in our words and in our actions. And now, if I and Gorgias are stumbling, [461d] here are you who should raise us up. And I for my part am determined to retract any error into which you may think that I have fallen, though only upon one condition.

POLUS: What condition?

SOCRATES: That you abbreviate, Polus, the excessive length of speech, in which you indulged at first.

POLUS: What! Do you mean that I may not use as many words as I please?

[461e] SOCRATES: Only to think, my friend, that having come on a visit to Athens, which values free speech more any other city in Greece, you, when you got here, and you alone, should be deprived of the power of speech — that would be hard indeed. But then consider my case: shall not I be very roughly used if, when you are making a long oration, and refusing to answer what you are asked, I am compelled to stay and listen to you, [462a] and may not go away? I say, rather, if you have a real interest in the argument, or, to repeat my former expression, have any desire to set it on its legs, take back any statement which you please. And in your turn ask and answer, like myself and Gorgias — refute and be refuted. For I suppose that you would claim to know what Gorgias knows, would you not?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And you, like him, invite any one to ask you about anything which he pleases, and you will know how to answer him?

POLUS: To be sure.

[462b] SOCRATES: And now, which will you do, ask or answer?

POLUS: I will ask. And do you answer me, Socrates, the same question which Gorgias, as you suppose, is unable to answer. What is rhetoric?

SOCRATES: Do you mean what sort of an art?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: To say the truth, Polus, it is not an art at all, in my opinion.

POLUS: Then what, in your opinion, is rhetoric?

SOCRATES: A thing which, as I was lately reading in a book of yours, [462c] you say that you have made an art.

POLUS: What thing?

SOCRATES: I would say a sort of knack.

* The Greek is empeiria, "experience." Rhetoric is something that you pick up incidentally, not a proper art to be studied and learned. Note that earlier (448c), Polus was praising experience (empeiria) as the basis for art or skill (tekhnē). Socrates is, in other words, putting Polus and his "art" down.

POLUS: Does rhetoric seem to you to be a knack?

SOCRATES: That is my view, but you may be of another mind.

POLUS: A knack for what?

SOCRATES: A knack for producing a sort of delight and gratification.

POLUS: And if able to gratify others, must not rhetoric be a fine thing?

SOCRATES: What are you saying, Polus? [462d] Why do you ask me whether rhetoric is a fine thing or not, when I have not as yet told you what rhetoric is?

POLUS: Did I not hear you say that rhetoric was a sort of knack?

SOCRATES: Will you, who are so desirous to gratify others, afford a slight gratification to me?

POLUS: I will.

SOCRATES: Will you ask me, what sort of an art is cookery?

POLUS: What sort of an art is cookery?

SOCRATES: Not an art at all, Polus.

POLUS: What then?

SOCRATES: I would say a knack.

POLUS: In what? I wish that you would explain to me.

[462e] SOCRATES: A knack for producing a sort of delight and gratification, Polus.

POLUS: Then are cookery and rhetoric the same?

SOCRATES: No, they are only different parts of the same profession.

POLUS: Of what profession?

SOCRATES: I am afraid that the truth may seem discourteous, and I hesitate to answer, lest Gorgias imagine that I am making fun of his own profession. [463a] For whether or not this is that art of rhetoric which Gorgias practices I really cannot tell. From what he was just now saying, nothing appeared of what he thought of his art, but the rhetoric which I mean is a part of a not very creditable whole.*

* Socrates' beef is not that Gorgias failed to clarify how rhetoric had to do with verbal persuasion (peithō logois, "persuasion through speeches"); on that Gorgias was clear. It's that Gorgias failed to convince Socrates that rhetoric is an "art," a tekhē, something that requires time and intellectual effort to study, to understand, and to practice properly. Note that tekhnē is the root of English "technology." In a way, rhetoric looks to Socrates not like a technology but just something you pick up or even have a natural knack for, as pointed out in an earlier note.

GORGIAS: A part of what, Socrates? Say what you mean, and never mind me.

SOCRATES: In my opinion then, Gorgias, the whole of which rhetoric forms a part is not an art at all, but the habit of a bold and ready intelligence, which knows how to manage humankind. [463b] That habit I sum up under the word "flattery,"

* Socrates uses the word kolakeia, which will be a buzz word for this course. It means "flattery," the process not simply of praising someone else but of doing so mostly to gratify the person. Thus it could mean insincere praise motivated chiefly to gratify, or to win favor from, another. The idea that kolakeia ("flattery") is a form of gratification also leads to the idea that anything intended to gratify or to coddle or to pander to is a form of kolakeia. But kolakeia also implies the inferiority of the kolax, the "flatterer." For to gratify another is to place yourself at the disposal of another.

What that means is that words like kolakeia and kolax imply some combination (two or more) of the following items:

- Praise

- Falsehood or insincerity

- Ulterior motives

- Gratification

- Inferiority of the flatterer

Put differently, Socrates, by grouping rhetoric with flattery, denigrates it and, in the process, risks offending Gorgias and Polus.

and it appears to me to have many other parts, one of which is cookery, which may seem to be an art, but, as I maintain, is only a knack or routine and not an art at all. Another part is rhetoric, and personal adornment and sophistry are two others.

* Socrates uses the Greek sophistikē, short for sophistikē tekhnē, the "sophistic art," what sophists (see above) practice and teach. Note how Polus and Gorgias want to call it an "art" (tekhnē), though Socrates resists.

Thus there are four branches, and four different things answering to them. And Polus may ask, if he likes, [463c] for he has not as yet been informed, what part of flattery is rhetoric. He did not see that I had not yet answered him when he proceeded to ask a further question, whether or not I think rhetoric a fine thing. But I will not tell him whether rhetoric is a fine thing or not, until I have first answered, "What is rhetoric?" For that would not be right, Polus. But I shall be happy to answer, if you will ask me, what part of flattery rhetoric is.

POLUS: I will ask and do answer. What part of flattery is rhetoric?

[463d] SOCRATES: Will you understand my answer? Rhetoric, according to my view, is the ghost or counterfeit of a part of politics.

POLUS: And noble or ignoble?

SOCRATES: Ignoble, I would say, if I am compelled to answer, for I call what is bad ignoble, though I doubt whether you understand what I was saying before.

GORGIAS: By Zeus, Socrates, I cannot say that even I understand.

[463e] SOCRATES: I do not wonder, Gorgias, for I have not as yet explained myself, and our friend Polus, colt by name and colt by nature, is apt to run away.*

* Again, the name "Polus" means "colt."

GORGIAS: Never mind him, but explain to me what you mean by saying that rhetoric is the counterfeit of a part of politics.

SOCRATES: I will try, then, to explain my notion of rhetoric, [464a] and if I am mistaken, my friend Polus will refute me. We may assume the existence of bodies and of souls?

GORGIAS: Of course.

SOCRATES: You would further admit that there is a good condition for each of them?

GORGIAS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And is there something that may not be good in reality, but good only in appearance? I mean to say, that there are many persons who appear to be in good health, and whom only a physician or trainer will discern at first sight not to be in good health.

GORGIAS: True.

SOCRATES: And this applies not only to the body, but also to the soul. In either there may be that which gives the appearance of health, [464b] but not the reality.

GORGIAS: Yes, certainly.

SOCRATES: And now I will endeavor to explain to you more clearly what I mean.*

* This gets intricate; I have supplied a diagram below.

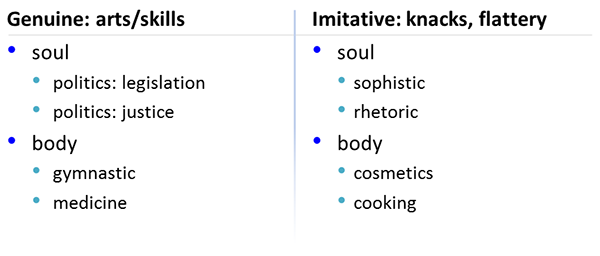

The soul and body are two different things. And each has its own two arts corresponding to each. There is the art of politics that has to do with the soul, and another art that has to do with the body. I do not know the name of this last art, but it can be described as having two parts. One of them is gymnastic, and the other is medicine. [464c] And in politics there is a legislative part, which answers to gymnastic, just as justice does to medicine. And the two parts run into one another: justice has to do with the same subject as legislation, and medicine with the same subject as gymnastic, but with a difference. So, there are these four arts, two attending on the body and two on the soul. All four aim at the highest good.

As for flattery, it knows, or rather guesses the natures of those arts. Thus it has distributed itself into four sham versions or simulations of them. [464d] Flattery puts on the likeness of some one or other of them, and pretends to be that which it simulates, and having no regard for people's highest interests, is always making pleasure the bait of the unwary, and deceiving them into the belief that it, flattery, is of the highest value to them. Cookery simulates the disguise of medicine, and pretends to know what food is the best for the body.*

* Note that ancient doctors were deeply concerned with diet. Thus the physician recommends foods based on their healthiness, the cook based only on their tastiness.

And if the physician and the cook had to enter into a competition in which children were the judges, or people who had no more sense than children, as to which of them best understands the goodness or badness of food, [464e] the physician would be starved to death. [465a] I deem cookery to be a kind of flattery and of an ignoble sort, Polus. For it's you I am now addressing. And I say this because flattery aims at pleasure without any thought of what is best. I do not call it an art, but only a knack, because it is unable to explain or to give a reason for the nature of its own uses.*

* It has no theoretical component; it's not a systematic field of knowledge.

And I do not call any irrational thing an art, but if you dispute my words, I am prepared to argue in defense of them.

[465b] Cookery, then, I maintain to be a flattery which takes only the shape of medicine. And cosmetics, in like manner, is a flattery which takes the form of gymnastic, and is harmful, false, ignoble, and unbefitting a free man. For it works deceitfully by the help of lines, and colors, and enamels, and garments, and making people affect a bogus beauty to the neglect of the true beauty which is given by gymnastic.

I would rather not be tedious, and therefore I will only say, [465c] after the manner of the logicians (for I think that by this time you will be able to follow):

As cosmetics are to gymnastic, so cookery is to medicine.

Or rather,

As cosmetics are to gymnastic, so sophistry is legislation.

And:

As cookery is to medicine, so rhetoric is to justice.*

*A diagram may help:

Sophistic and rhetoric are fake versions (knacks, forms of flattery) of legislation and of justice, these last being the real deal and worthy of study and mastery. The same goes for cosmetics and cooking in relation to gymnastic and medicine.

And this, I say, is the natural difference between the rhetorician and the sophist, but by reason of their near connection, they are apt to be jumbled up together.*

* Socrates makes sophistic and rhetoric out to be different, but only a little different: sophistic as tricky reasoning and rhetoric as tricky speaking. But both seem at home in either courts or legislature. Gorgias' surviving works seem to illustrate both kinds of trickiness.

Neither do they know what to make of themselves, nor do other people know what to make of them. [465d] For if the body governed itself, and were not under the guidance of the soul, and the soul did not make the effort to discern and discriminate between cookery and medicine, but allowed the body to be the judge of them, and if the standard of judgment was whether cookery or medicine provided bodily pleasure, then what Anaxagoras said, a saying with which you, my friend Polus, are well acquainted, would prevail far and wide: everything would be all mixed up together, and cookery, health, and medicine would mingle in an indiscriminate mass.

[466a] And now I have told you my notion of rhetoric, which is, in relation to the soul, what cookery is to the body. Now, I may have done something unexpected in making a long speech, seeing as I would not allow you to speak at length. But I think that I may be excused, because you did not understand me, and could make no use of my answer when I spoke shortly, and therefore I had to enter into an explanation. And if I likewise show myself unable to make use of your answer, I hope that you will speak at equal length. But if I am able to understand you, then let me have the benefit of your brevity, as is only fair. And now you may do what you please with my answer.

POLUS: What do you mean? Do you think that rhetoric is flattery?

SOCRATES: No, I said that it is a part of flattery. If at your age, Polus, you cannot remember, what will you do later, when you get older?

POLUS: And are the good rhetoricians regarded with contempt in cities, under the idea that they are flatterers?

[466b] SOCRATES: Is that a question or the beginning of a speech?

POLUS: I am asking a question.

SOCRATES: Then my answer is, that they are not regarded at all.

POLUS: How not regarded? Have they not very great power in cities?

* For Polus, skill in rhetoric can be a path to political influence and thus to power. Even in a democracy, persuasive politicians rule the people the way a king rules subjects — so Polus thinks. Remember how Gorgias said that with rhetoric, you could "rule others," and even make physicians and physical trainers your slave (425d-e)? It's that kind of power that Polus (and, later, Callicles) would exploit.

SOCRATES: Not if you mean to say that power is a good for the possessor.

POLUS: And that is what I do mean to say.*

* We are already at a key point of the argument, namely, the idea that power is for the benefit of the powerful. For Polus and Callicles (next and final interlocutor), the purpose of power is to aid the powerful in the realization of their ambitions and bodily desires, pleasure and so on. "It's good to be king," says the king in Mel Brooks' History of the World Part 1. For Socrates, power has only one purpose: to aid in achieving the good and the just.

SOCRATES: Then, if so, I think that they have the least power of all the citizens.

[466c] POLUS: What! Are they not like tyrants? They kill and despoil and exile anyone whom they please.*

* Tyrants, i.e., absolute monarchs and dictators, were often thought to be the happiest of people because their power freed them from the usual constraints and allowed them to achieve their every whim.

SOCRATES: By the dog, Polus, I cannot make out at each expostulation of yours, whether you are giving an opinion of your own, or asking a question of me.

POLUS: I am asking a question of you.

SOCRATES: Yes, my friend, but you ask two questions at once.

POLUS: How two questions?

SOCRATES: Why, did you not say just now that rhetoricians are like tyrants, [466d] and that they kill and despoil or exile any one whom they please?

POLUS: I did.

SOCRATES: Well then, I say to you that here are two questions in one, and I will answer both of them. And I tell you, Polus, that rhetoricians and tyrants have the least possible power in cities, [466e] as I was just now saying. For they do literally nothing that they want, but only what they think best.

POLUS: And is that not a great power?

SOCRATES: Polus has already said the reverse.

POLUS: Said the reverse! No, that is what I assert.

SOCRATES: No, by ――* no, that is not what you assert. For you say that power is a good to him who has the power.

* It looks as if Socrates is about to say something like "by Zeus" or "by the dog," but stops short. The conversation is getting intense, and Socrates may not want to invoke divinity as a kind of swear word. (That is more or less the ancient commentator's explanation.) Socrates and Polus are at loggerheads because Socrates thinks that power is bad for people who misuse it. Polus thinks that power is its own justification, no matter how it is used.

POLUS: I do.

SOCRATES: And would you maintain that if a fool does what he thinks best, this is a good, and would you call this great power?

POLUS: I would not.

[467a] SOCRATES: Then you must prove that the rhetorician is not a fool, and that rhetoric is an art and not a form of flattery — and that way you will have refuted me. But if you leave me unrefuted, why, the rhetoricians who do what they think best in cities, and the tyrants, will have nothing upon which to congratulate themselves, if as you say, power is indeed a good, admitting at the same time that what is done without sense is an evil.

POLUS: Yes; I admit that.

SOCRATES: How then can rhetoricians or tyrants have great power in cities, unless Polus can refute Socrates, and prove to him that they do as they will?

[467b] POLUS: This man ――*

* Polus is either so stunned that he cannot finish what he started to say (maybe, "This man is nuts!"), or perhaps Socrates interrupts before Polus can finish. Either way, Polus thinks Socrates is a bit daft not to acknowledge that power is a self-justifying good.

SOCRATES: I say that they do not do as they want; now refute me.

POLUS: Why, have you not already said that they do as they think best?

SOCRATES: And I say so still.

POLUS: Then surely they do as they want?

SOCRATES: I deny it.

POLUS: But they do what they think best?

SOCRATES: Yes.

POLUS: That, Socrates, is monstrous and absurd.

SOCRATES: Enough with the insults, peerless Polus, as I may say in your own peculiar style. [467c] But if you have any questions to ask me, either prove that I am in error or give the answer yourself.

POLUS: Very well, I am willing to answer that I may know what you mean.

SOCRATES: Do people appear to you to want that which they are doing? Or do they want some other, further end, for the sake of which they do a thing? When they take medicine, for example, at the bidding of a physician, do they want the drinking of the medicine, which is painful, or the health part, for the sake of which they drink the medicine?

[467e] POLUS: Clearly, the health part.

SOCRATES: And when people go on a voyage or engage in business, they do not want that which they are doing at the time. For who would desire to take the risk of a voyage or the trouble of business? But they want to have the wealth for the sake of which they go on a voyage.

POLUS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And is this not universally true? If someone does something for the sake of something else, that person wants not that which he or she does, but that for the sake of which he or she does it.

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And are not all things either good or evil, or in between?

POLUS: To be sure, Socrates.

SOCRATES: Wisdom and health and wealth and the like you would call goods, and their opposites evils?

POLUS: I would.

SOCRATES: And the things which are neither good nor evil, [468a] and which partake sometimes of the nature of good and at other times of evil, or of neither, things like sitting, walking, running, sailing; or, again, wood, stones, and the like — these are the things which you call neither good nor evil?

POLUS: Exactly so.

SOCRATES: Are these in-between things done for the sake of the good, or the good for the sake of the in-between?

[468b] POLUS: Clearly, the in-between for the sake of the good.

SOCRATES: When we walk we walk for the sake of the good, and under the idea that it is better to walk, and when we stand we stand equally for the sake of the good?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And when we kill a man we kill him or exile him or confiscate his goods, because, as we think, it will conduce to our good?

POLUS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: People who do any of these things do them for the sake of the good?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: And did we not admit that in doing something for the sake of something else, we do not want those things which we do, [468c] but that other thing for the sake of which we do them?

POLUS: Most true.

SOCRATES: Then we do not want simply to kill a man or to exile him or to despoil him of his goods, but we want to do that which conduces to our good, and if the act is not conducive to our good, we do not want it. For we want, as you say, that which is our good, but that which is neither good nor evil, or simply evil, we do not want. Why are you silent, Polus? Am I not right?

POLUS: You are right.

[468d] SOCRATES: Hence we may conclude that if any one, whether a tyrant or a rhetorician, kills another or exiles another or deprives another of his property, under the idea that the act is for his own interests, when really it does not serve his interests, that person may be said to do what seems best to that person?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: But does he do what he wants if he does what is bad for him? Why do you not answer?

POLUS: Well, I suppose not.

[468e] SOCRATES: Then if great power is a good as you allow, will such a one have great power in a city?

POLUS: He will not.

SOCRATES: Then I was right in saying that a man may do what seems good to him in a city, but not have great power, nor do what he wants.

POLUS: As if you, Socrates, would not like to have the power of doing what seemed good to you in the city, rather than not! No, you would not be jealous when you saw any one killing or robbing or imprisoning whomsoever he pleased. Oh, no, not you!

SOCRATES: Do you mean justly or unjustly?

[469a] POLUS: In either case, is the powerful man not equally to be envied?

SOCRATES: Please, stop, Polus!

POLUS: Why "Please, stop!"?

SOCRATES: Because you ought not to envy wretches who are not to be envied, but only to pity them.

POLUS: And are those of whom I spoke wretches?

SOCRATES: Yes, certainly they are.

POLUS: And so you think that whoever slays any one whom he pleases, and justly slays him, is pitiable and wretched?

[469b] SOCRATES: No, I do not say that about him. But neither do I think that he is to be envied.

POLUS: Were you not saying just now that he is wretched?

SOCRATES: Yes, my friend, if he killed another unjustly, in which case he is also to be pitied. But even if he killed him justly he is not to be envied.

POLUS: At any rate you will allow that whoever is unjustly put to death is wretched, and to be pitied?

SOCRATES: Not so much, Polus, as anyone who kills him, and not so much as the one who is justly killed.

POLUS: How can that be, Socrates?

SOCRATES: It may be because doing injustice is the greatest of evils.

POLUS: But is it the greatest? Is not suffering injustice a greater evil?

SOCRATES: Certainly not.

POLUS: Then would you rather suffer wrong than do wrong?

[469c] SOCRATES: I would not like either, but if I must choose between them, I would rather suffer than do wrong.

POLUS: Then you would not wish to be a tyrant?

SOCRATES: Not if you mean by tyranny what I mean.

POLUS: I mean, as I said before, the power of doing whatever seems good to you in a city: killing, banishing, doing in all things as you like.

SOCRATES: Well then, illustrious friend, when I have said my say, do you reply to me. [469d] Suppose that I go into a crowded public square, and take a dagger under my arm. "Polus," I say to you, "I have just acquired rare power," and I become a tyrant. For if I think that any of these men whom you see ought to be put to death, the man whom I have a mind to kill is as good as dead. And if I am disposed to break his head or tear his garment, he will have his head broken or his garment torn in an instant. [469e] Such is my great power in this city. And if you do not believe me, and I show you the dagger, you would probably say, "Socrates, in that sort of way any one may have great power — he may burn any house which he pleases, and the docks and war ships of the Athenians, and all their other vessels, whether public or private. But can you believe that this mere doing as you think best is great power?"

POLUS: Certainly not such doing as this.

[470a] SOCRATES: But can you tell me why you disapprove of such a power?

POLUS: I can.

SOCRATES: Why then?

POLUS: Why, because whoever did as you say would be certain to be punished.

SOCRATES: And punishment is an evil?

POLUS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And you would admit once more, my good sir, that great power is a benefit to a man if his actions turn out to his advantage, and that this is the meaning of great power. And if not, then his power is an evil and is no power. [470b] But let us look at the matter in another way. Do we not acknowledge that the things of which we were speaking, the infliction of death, and exile, and the deprivation of property, are sometimes a good and sometimes not a good?

POLUS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: About that you and I may be supposed to agree?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: Tell me, then, when do you say that they are good and when evil — what principle do you lay down?

POLUS: I would rather, Socrates, that you answer as well as ask that question.

[470c] SOCRATES: Well, Polus, since you would rather have the answer from me, I say that they are good when they are just, and evil when they are unjust.

POLUS: You are hard to refute, Socrates, but might not a child disprove that statement?

SOCRATES: Then I will be very grateful to the child, and equally grateful to you if you will refute me and deliver me from my foolishness. And I hope that you will refute me, and will not get tired of doing good to a friend.

POLUS: Yes, Socrates, and I need draw my examples from long ago. [470d] Events which happened only a few days ago are enough to refute you, and to prove that many people who do wrong are happy.

SOCRATES: What events?

POLUS: You see, I presume, that Archelaus the son of Perdiccas is now the ruler of Macedonia?*

* A kingdom to the north of Athens.

SOCRATES: At any rate I hear that he is.

POLUS: And do you think that he is happy or miserable?

SOCRATES: I cannot say, Polus, for I have never had any acquaintance with him.

[470e] POLUS: And you cannot tell at once, and without having an acquaintance with him, whether a man is happy?

SOCRATES: Most certainly not.

POLUS: Then clearly, Socrates, you would say that you did not even know whether the king of Persia* was a happy man?

* Proverbial for his immense power.

SOCRATES: And I would speak the truth. For I do not know how he stands in the matter of education and justice.

POLUS: What! Does all happiness consist of that?

SOCRATES: Yes, indeed, Polus, that is what I believe. The men and women who are gentle and good are also happy, as I maintain, and the unjust and evil are miserable.

[471a] POLUS: Then, according to your doctrine, the aforementioned Archelaus is miserable?

SOCRATES: Yes, my friend, if he is wicked.

POLUS: That he is wicked I cannot deny. For he had no title at all to the throne which he now occupies, he being only the son of a woman who was the slave of Alcetas the brother of Perdiccas. He himself therefore was, strictly speaking, the slave of Alcetas.*

* It is true that Archelaus murdered rivals to the throne, but the Macedonian monarchy had no law of succession and it was common to do so. Otherwise, Socrates' portrait of the king seems harsh. There is evidence that he was legitimate and fully royal. He was pro-Athenian and was a patron of Athenian poets. He was deeply committed to bringing Macedonia into the mainstream of Greek culture. Still, in Plato's time (post-Archelaus), Athens had a really fraught relationship with the kingdom to the north.

And if he had meant to do rightly he would have remained his slave, and then, according to your doctrine, he would have been happy. But now he is unspeakably miserable, for he has been guilty of the greatest crimes. [471b] In the first place he invited his uncle and master, Alcetas, to come to him, under the pretence that he would restore to him the throne which Perdiccas has usurped, and after entertaining him and his son Alexander,*

* Not Alexander the Great, who lived almost a century later. But both Alexanders were of the Macedonian royal family.

who was his own cousin, and nearly the same age as he. And making them drunk, he threw them into a wagon and carried them off by night, and killed them, and got both of them out of the way. And when he had done all this wickedness, he never discovered that he was the most miserable of all people, and was very far from repenting. Shall I tell you how he showed his remorse? [471c] He had a younger brother, a child of seven, who was the legitimate son of Perdiccas, and to him the kingdom rightfully belonged. Archelaus, however, had no mind to bring him up as he ought, or to restore the kingdom to him. That was not his notion of happiness. But not long afterwards, he threw him into a well and drowned him, and declared to his mother Cleopatra*

* Not the later Cleopatra, queen of Egypt.

that he had fallen in while running after a goose, and had been killed. And now as he is the greatest criminal of all the Macedonians, he may be supposed to be the most miserable and not the happiest of them. And I dare say that there are many Athenians, and you would be at the head of them, [471d] you who would rather be any Macedonian than other Archelaus!*

* Polus is again being sarcastic. He means that anyone would love to trade places with this Archelaus fellow, a king who does anything he wants with impunity. Anyone, that is, but crazy Socrates. . . .

SOCRATES: I praised you at first, Polus, for being a rhetorician rather than a reasoner. And this, as I suppose, is the sort of argument with which you fancy that a child might refute me, and by which I stand refuted when I say that the unjust man is not happy. But, my good friend, where is the refutation? I cannot admit a word which you have been saying.

[471e] POLUS: That is because you will not. For you surely must agree with me.

SOCRATES: Not so, my simple friend. I do not agree with you because you want refute me in the way that rhetoricians go about it in courts of law. For there the one side thinks that they refute the other when they bring forward a number of witnesses of good reputation as proof of their allegations, and their adversary has only a single witness or none at all. [472a] But that kind of proof is of no value where truth is the aim. A man may often be sworn down by a multitude of false witnesses who have a great air of respectability. And in this argument nearly every one, Athenian and foreigner alike, would be on your side, if you would bring witnesses to disprove my statement. You may, if you will, summon Nicias the son of Niceratus,*

* We will meet the famous general Nicias later in the course.

and let his brothers, who gave the row of tripods which stand in the sanctuary of Dionysus, come with him. [472b] Or you may summon Aristocrates, the son of Scellias, who is the giver of that famous offering which is at Delphi. Summon, if you will, the whole house of Pericles,*

* Pericles, the most famous of all Athenian statesman. More about him later.

or any other great Athenian family whom you choose. They will all agree with you. Only I am left alone and cannot agree, for you do not convince me. Although you produce many false witnesses against me, in the hope of depriving me of my inheritance, which is the truth.*

* Socrates imagines a court case in which clever lawyer Polus sues Socrates to deprive him of his inheritance. In the image, Socrates' "inheritance" is the Truth. And Polus would gladly rob Socrates of the Truth, Socrates' most precious possession.

[472c] But I consider that nothing worth speaking of will have been effected by me unless I make you the one witness of my words. Nor by you, unless you make me the one witness of yours.*

* Socrates means that the winner of this argument will be the one who gets the other to change his mind — to agree finally to be a "witness" for the other side.

No matter about the rest of the world. For there are two ways of refutation, one which is yours and that of the world in general. But mine is of another sort — let us compare them, and see how they differ. For indeed, we disagree over matters about which it is honorable to have knowledge, but disgraceful not to have knowledge. To know or not to know happiness and misery — that is the chief of them. And what knowledge can be nobler? Or what ignorance more disgraceful than this? [472d] And therefore I will begin by asking you if it is not the case that you think a man who is unjust, and is doing injustice, can be happy, seeing as you take Archelaus to be unjust yet happy. May I assume that that is how you think of these things?

POLUS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: But I say that that is an impossible state of affairs; here is one point about which we disagree. Well, do do you also mean to say also that if he meets with retribution and punishment he will still be happy?

POLUS: Certainly not. In that case he will be most miserable.

[472e] SOCRATES: On the other hand, if the unjust man is not punished, then, according to you, he will be happy?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: But in my opinion, Polus, the unjust man or the doer of unjust actions is miserable in any case, more miserable, however, if he is not punished and does not meet with retribution, and less miserable if he is punished and meets with retribution at the hands of gods and human beings.*

* On the face of it, both Socrates and Polus hold positions consistent with the broader outlook of each. Polus would rather enjoy rewards sooner than later; he would rather spend than invest. The more power you have, the more you have to invest. Consistent with that, he is more interested in avoiding unpleasantness for the short term, and does not worry about whether that is good in the long term. Socrates is playing a long game. Holding off on enjoying immediate rewards often enhances the reward long-term; he would rather invest and collect interest. So, too, enduring unpleasantness — punishment, medicine, sort of the same thing — now may bring a better future. For even harsh punishment offers one a chance at correction, the chance to be better, which always is better. In theory, that could be said to apply even in the case of capital punishment. Cut short an evil life now and you save the subject from continuing to collect bad karma. That matters in the afterlife, as we shall see in the myth at the end of the dialogue.

[473a] POLUS: You are maintaining a strange doctrine, Socrates.

SOCRATES: I will try to make you agree with me, O my friend, for as a friend I regard you. Then these are the points at issue between us, are they not? I was saying that to do wrong is worse than to suffer wrong, right?

POLUS: Exactly so.

SOCRATES: And you said the opposite?

POLUS: Yes.

SOCRATES: I said also that the wicked are miserable, and you refuted me?

POLUS: By Zeus, I did.

[473b] SOCRATES: Or so you think, Polus.

POLUS: Yes, and I rather suspect that I was right.

SOCRATES: You further said that the wrongdoer is happy if he is unpunished?

POLUS: Certainly.

SOCRATES: And I affirm that he is most miserable, and that those who are punished are less miserable — are you going to disprove this proposition also?

[473b] POLUS: A proposition which is harder to disprove than that other one, Socrates!*

* Polus is being sarcastic. He thinks it will be a piece of cake.

SOCRATES: Say rather, Polus, impossible. For who can disprove the truth?