Persuasion in Ancient Greece

Andrew Scholtz, Instructor

Study Guides. . .

Early Political Theory and Practice

Readings Journal Entries

What in these readings, what for us now, legitimizes various ways of ruling and being ruled? How, for our authors, how for us now, can the legitimacy of rulership be made persuasive?

ALTERNATE TOPICS:

- How can we apply any of the 26-Jan theory readings to today's reading?

- Can you come up with a good question pertaining to these readings, one deserving discussion in class — something unclear or the like? (If you choose this last option, make sure you get your question in early so I can maybe bring it up in class.)

Goal of Class

- To gain a sense of earlier (pre-420s BCE)

- practices

- attitudes

- "proto-theory"

- To understand the place of peitho in all that

Materials to Be Studied

These readings will have us looking at a variety of sources, including

- Epic poetry (Homer and Hesiod)

- Elegiac and lyric poetry (Theognis, the Harmodius and Aristogeiton skolia)

- Historical prose (Thucydides, Herodotus)

- Philosophical prose (Plato, Democritus, etc.)

- Sophists

Some, but not all, of this material pertains to democracy. Some pertains to more fundamental questions, e.g., the legitimacy of political-judicial institutions.

Background with Links to Optional Reading

The Cleisthenic Reforms, "Prequel," etc.

On Tuesday, I will be lecturing briefly on the first phases of Athens' evolution toward radical democracy, fully in place by the middle of the fifth century BCE.

What follows provides a compressed preview of that lecture.

Basically, we are talking about a two-stage process with a big bump in the middle:

- From birth-based aristocracy to wealth-based, limited oligarchy with elements of democracy, i.e., Solon's constitutional reforms of the 590s BCE.

- BUMP: The tyranny (extra-constitutional dictatorship or junta) exercised by Peisistratus and his sons on and off, 560-510 BCE.

- From oligarchy to limited democracy with the reforms of Cleisthenes in 508/7 BCE. (See readings page, Herodotus on the Cleisthenic reforms, for more.)

Here follows a timeline summarizing those developments:

| ca. 620 | Draco's law code. Sources describe Draco's laws (which they call thesmoi) as the first written law code at Athens. (Evidently, they prescribed harsh punishments for a variety of infractions, but that still represents an advance because a written code of laws.) | |

| 594-593 (?) | Solon's constitutional reforms and law code at Athens. Not exactly democratic, but still an advance, Solon's reforms featured:

|

|

| 560-510 | On-and-off tyranny of Peisistratus and sons ("Peisistratids") at Athens. (Peisistratus was the power at Athens, but held no official office. Nor did he at any point he roll back the Solonian constitution.) | |

| 550 | Sparta dominant power in Peloponnese. | |

| 507 | Cleisthenic reforms (Cleisthenic democracy). Athenian Cleisthenes, in a power struggle with fellow aristocrat Isagoras, seeks to gain the upper hand by allying himself with the common folk at Athens. In the process, he institutes reforms; some regard those as the beginning of democracy in the city.

To sum up, those reforms involved:

The effect of all this was to make clear that the native-born adult free male inhabitants of Athens and its environs were full members of a political collective with the right to participate in politics. The popular assembly (the ekklēsia, see below) will have existed long before and will have wielded power. Previously, though, there will have been little sense that all the people, even the poorest, had a part in governing. That changed when Cleisthenes, with the people's help, instituted his reforms. It's not clear that the new order was yet being called "democracy" (dēmokratia, see below). One of Cleisthenes' rallying cries may have been isonomia, "equality before the law." |

Brief Sketch of Athenian Democracy, ca. 461-404 BCE

As we research and write our papers, it will be useful to have a sense of what the mature Athenian democracy was and how it worked. Hence the following outline of Athenian democracy such it was from the time of Ephialtes' reforms (461 BCE) until the oligarchic overthrow of democracy following Athens' defeat in the Peloponnesian War. (Athens and allies v. Sparta and allies, 431-404 BCE. Democracy was dissolved in 404 and restored in 403 BCE.)

General Observations

Very much unlike American or parliamentary (Canadian, European, etc.) systems, Athenian democracy was not representative (elected officials representing the people). Nor did it feature anything resembling the American separation of powers: separate executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

Rather, the Athenian system exemplified radical, direct democracy. It was "radical" because it was democratic to the core, extending full, or nearly full, participation throughout the voting citizen class (pay for political service would eventually make it possible for all members of the Athenian political collective, even the poor, to participate at all levels). It was "direct" because representatives did not (for the most part) come between citizens and the process of governing. Rather, the people governed themselves. To quote Christopher Blackwell,

Democracy in Athens was not limited to giving citizens the right to vote. Athens was not a republic, nor were the People governed by a representative body of legislators. In a very real sense, the People governed themselves, debating and voting individually on issues great and small, from matters of war and peace to the proper qualifications for ferry-boat captains. . . . (Athenian Democracy: a brief overview, p. 2)

Related to this idea of democracy as citizens ruling themselves was the idea that freedom was the core principle underlying the system, also that offices should be held in rotation: individuals should not be allowed to settle into political office in a permanent sort of way. To quote Aristotle:

The underlying principle of democracy is freedom, and it is customary to say that only in democracies do individuals have a share in freedom, for that is what every democracy makes its aim. There are two main aspects of freedom: 1) being ruled and ruling in turn, since everyone is equal according to number, not merit, and 2) to be able to live as one pleases. (Politics 1317a40-b13, translated Thomas R. Martin, with Neel Smith & Jennifer F. Stuart, Dēmos · Classical Athenian Democracy site)

It was, however, in other ways a very limited democracy. Women lacked the franchise (citizen rights). Athens had a large number of resident foreigners lacking political prerogatives. It had as well a vast population (relatively speaking) of slaves utterly bereft of rights.

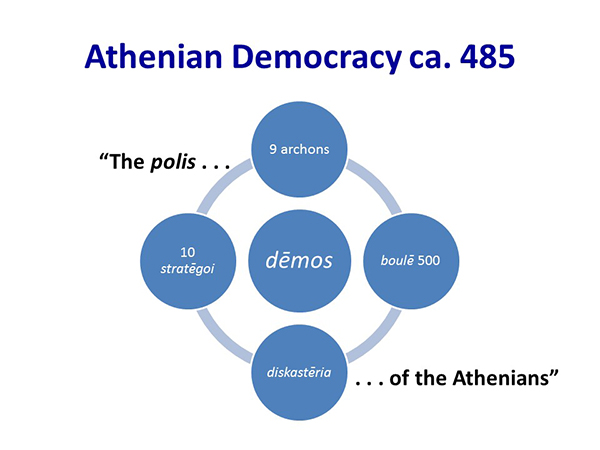

Here's a graphic to help put things in perspective:

And here's an explanation of that graphic:

The polis of the Athenians (hē polis hē tōn Athēnaiōn)

That was the official name of the Athenian state, and it referred principally to the body politic as, precisely, a political body. To quote Demosthenes (4th-cent. BCE politician) addressing a citizen jury, "When I use the word 'you,' I mean the polis" (On the Crown 88).

Dēmos, Assembly (ekklēsia)

The dēmos, the "people" or "citizenry" of Athens, was composed of all voting male Athenian citizens, 18 years of age and up. We call meetings of the dēmos "assembly meetings" (ekklēsia, the "popular assembly"). The dēmos met frequently during the year to debate and to enact policy. In general, no more than 8,000 citizens would attend a given meeting of the assembly.

The only requirement for membership in the dēmos was Athenian parentage. Starting in 451 BCE, one needed both parents to be Athenians to qualify for citizenship. It was rare for foreigners to gain citizenship.

- There was no property requirement for citizenship.

All members of the dēmos had the right to address the assembly, though in practice, relatively few did. Isēgoria, "equal speech," refers to this right. Parrhēsia, "frank" or "free speech," refers to the freedom of speech, the frankness or sincerity, that assembly speakers were expected to employ.

- Population. At the highpoint of the classical Athenian democracy (around 431 BCE), there were maybe 60,000 Athenians. I mean persons with citizen status: men, women, and children, not simply voting male members of the dēmos. In addition, Athens and its territory of Attica will have had about 20,000 resident aliens, sort of like those with green cards, many/most of whom will have been Greek, just not Athenian. We call them "metics" (metoikoi, "dwellers with us"). Non-Athenians temporarily in Attica (traders and such) were called xenoi, "foreigners" — again, a mix of Greeks and non-Greeks. Finally, Attica had about 100,000 slaves living within its boundaries. Think about it: 100k slaves to 60k citizens.

The dēmos was the sovereign political entity at Athens. They were "the boss." Politicians and generals were subject to their power. Hence the name for the system as a whole: dēmokratia, "people power."

The dēmos meeting in assembly (ekklēsia, the word is where "church" comes from) would vote on two kinds of bills:

- Decrees, or psēphismata, tended to be for specific purposes: going to war, building a wall, or the like

- Nomoi, "laws," were statutes with a broader and more permanent function, for instance, changes to the constitution. Things like homicide and (dis)qualification from/for various political roles were covered by nomoi

Council (boulē) of Five Hundred

The Council of 500 was composed of fifty citizens drawn from each of the ten Cleisthenic tribes, and serving for one year. The selection process was by lottery; no citizen could serve more than twice. Unlike the assembly (where all citizens were members), it was a representative body, though a seriously democratic one. The minimum age was thirty.

The council met every day except holidays and had general supervisory functions over many aspects of government. But its chief function was preparation of the agenda for assembly debate.

(From 461 BCE on the Areopagus Council had no political role.)

10 stratēgoi ("generals")

These were the military commanders. Each was chosen by vote (not lottery). They served without pay. By the mid 400s BCE, they were political leaders as well as military. (Later, they returned to being mostly military leaders.)

They commanded in war but were still subject to the power of the dēmos.

9 Archons

In earlier times, they were the aristocratic rulers of Athens. With the advent of democracy, their role diminished, and as the democracy matured, these nine archons ("officials," "magistrates") became increasingly less powerful, reaching the point that they served a mainly ceremonial role. Selection was by lottery; eventually, any Athenian citizen could serve. The archons, unlike the generals, were paid for their service under the mature democracy.

Dikastēria, ēliaia, the "People's Courts"

Homicide trials were handled by special courts with special juries, for instance, the Areopagus court, which tried cases of intentional homicide, as in the Eumenides. The members of the Areopagus were all ex-archons and served for life. Other cases of homicide were tried by a group of 51 jurors called ephetai. We think that these last were a kind of subcommittee chosen by lottery from the Areopagus-council membership. In any case, these homicide juries should not be viewed as democratic.

Other cases were handled by the explicitly democratic "people's courts" (ēliaia), with large juries composed of citizens who had willingly submitted their names and were assigned to juries by lottery. Juries for these "people's courts" can, therefore, be considered as representative of the entire dēmos, and jury trials in the ēliaia, as justice of a fundamentally democratic character.

For Further Reading Online (valid, citable secondary sources)

- "Athenian Democracy: a brief overview," by Christopher W. Blackwell at the DĒMOS: Classical Athenian Democracy site

- "Lecture 16 - Radical Democracy in the Age of Pericles," by Nick Rauh at Perdue University

Links to Optional Web Readings @ Perseus

Just below are Perseus links to readings from Thomas Martin's An Overview of Classical Greek History from Homer to Alexander. Note that you don't need to click back to this page for each of the links. Staring with the first one, you can advance forward using the blue "forward" arrows in the Perseus window.

- 6.29. VI. The Struggle between Isagoras and Cleisthenes

- 6.30. VI. The Democratic Reforms of Cleisthenes

- 6.31. VI. Persuasion and Cleisthenic Democracy

Quiz

On TU, 14-Feb, there will be a VERY SHORT QUIZ of material covered in class assignments and lectures from 17-Jan (Introduction to class) through and including 14-Feb ("Proto-Political Theory, Practice," this day's class).

- Readings and lecture 26-Jan, "Modern theory and related 1," will NOT be covered.

The quiz will be very short, very plain, very non-interpretive and straightforward — a "fact-check" quiz more than anything else to encourage attentive reading and in-class listening.

It will also be MULTIPLE CHOICE, including a "none of the above" choice for each question.

Specifically, expect:

- Multiple choice questions targeting. . .

- Class-assigned readings, for which know. . .

- authors (where appropriate, you won't have authors' names for everything)

- titles (where appropriate, you won't have titles for everything)

- characters, key actors/speakers (where appropriate)

- basic and crucial content info

- key terms and concepts listed below, for which consult

- your notes

- our target texts

- my PowerPoints

- Terms page

- This quiz will not test knowledge of the "Brief Sketch of Athenian Democracy, ca. 461-404 BCE" (see above) except insofar as elements of that democracy sketch. . .

- Clearly figure in relevant readings

- Appear in the list of terms, below

Which means that I won't be asking you about the Council of 500. Dēmos, however, is a concept central to much that we've done so far. Know it!

Review Terms List. (For definitions, see "Terms")

- But please also review assigned readings, which this list does not necessarily address.

- agōn

- Aphrodite

- Areopagus

- dēmos

- dialectic

- epideixis

- erastēs

- erōmenos

- erōs

- himeros

- Pandemos

- pederasty

- peithō

- rhetoric