Persuasion in Ancient Greece

Andrew Scholtz, Instructor

Study Guides. . .

Plato's Gorgias

Text Access

Online web doc via this site.

Schedule of Readings

IT IS IMPORTANT that we all read, and on time, the first text to be discussed this semester: Plato's Gorgias, which we'll do in two parts. Thus for. . .

- Thur, 19-Jan, read 447a-481b

- Tue, 24-Jan, read 481b-527e

. . . all as per "Assignments" page.

This is especially important as you'll be writing and "PowerPointing" on the Gorgias for an assignment due already the second Friday of classes.

More about that here; what follows is to introduce you to our first text, and to set you up for interesting and lively conversation on it.

Journal Questions

Thur 19-Jan

Let me pose for you a question as a start to your own adventure in critical thinking this semester:

DOES PLATO (or his mouthpiece, Socrates) TREAT RHETORIC FAIRLY?

That can be approached various ways. If you like, or if it helps, think of it in terms of any or all of the following (your call!),

- Does rhetoric in Plato's Gorgias find an adequate or accurate definition?

- Or does the dialogue deploy a "straw man" argument against rhetoric, one where you define your target in such a way that it's easy to shoot down?

- Does Socrates provide a satisfying response to the arguments of his interlocutors (co-speakers)? Do they respond adequately to Socrates?

- If you had to pick a winner in this debate (notice I said "had" to, you may not want to), who would it be? Why?

- Whatever the message is that emerges from the dialogue, does it mesh with your idea of speech and its uses? How so, how not?

Additional Questions (not journal prompts)

To approach the question posed just above, it may help to think about the following as you read:

- What seem to be Socrates' political commitments? Pro-democracy, Anti-? In between? Or is it not so obvious? What about those of his interlocutors, namely, Gorgias, Polus, and Callicles? How like or different do they all seem to be politically or intellectually to one another?

- What arguments defended or attacked in this dialogue? By whom and how?

- How does Socrates respond to Gorgias, Polus, and Callicles, both in terms of substance, but also of what might be termed style or approach — rhetoric?

- Ditto for Socrates' interlocutors: how do they respond to Socrates?

Tue 24-Jan

IS SOCRATES' PERSUASION regarding Callicles' natural-law hedonism "PERSUASIVE"? WHY OR WHY NOT?

Does Socrates use a kind rhetoric? Anti-rhetoric? Is it skillfully handled? Ineptly? Could Socrates have gone about it differently and maybe won a convert? Does Socrates win you as a convert? Why or why not?

General Introduction

General Introduction

What kind of talk is the best kind of talk to govern with? Should our leaders merely tell the truth? Or is there more to it than that? And should they ever lie? When talking someone into or out of something, do the ends (a noble cause!) always or ever justify the means (deception, manipulation, etc.)? Or should there be an ethics of the verbal means one uses?

Like a pair of bookends, two of Plato's writings, the Gorgias and the Phaedrus, works addressing just such questions, stand at the beginning and end of our course. About Plato, Alfred North Whitehead, the twentieth-century British philosopher, has written:

The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. (Process and Reality, p. 39)

I cite Whitehead just to impress on you Plato's inescapability (though I would question the demotion of later philosophy to the status of "footnotes").

More on the general contours of Plato's philosophy later (it will matter). For now, let's concentrate on his Gorgias, and the concerns it specifically addresses.

|

The Gorgias concerns, among other things, rhetoric: what it is and its value to the city, in other words, its political, practical, and moral value, especially in contrast with philosophy. Thus the Gorgias makes for an excellent place to begin, as it introduces key questions having to do with what persuasion is, how it works, and what it's good for.

It also may bear mentioning that Plato's Gorgias seems to provide the very first preserved use of the word "rhetoric," in Greek, rhētorikē (tēn kaloumenēn rhētorikēn, "the art which is called rhetoric," 448d = p. 32).

Now, I don't think it's giving away anything to say that Socrates, the dialogue's star speaker, does not, in fact, find rhetoric good for very much at all — not, at least, in this dialoge. Rather, it is philosophy that, as far as Socrates is concerned, should command the attention of those who would lead the city.

In that opinion, he is opposed by three interlocutors (co-speakers) who defend rhetoric as useful not just to the city but (and perhaps more importantly) to persons of ambition.

To summarize, let me quote something I have written elsewhere:

Plato's Gorgias, named for one of the great sophist-rhetoricians of the fifth and early fourth centuries BCE, plays like a three-act drama.

After a brief overture, Act One has Socrates dispute the title character's [Gorgias'] contention that to lead effectively, a city’s leaders need only master the art of persuasion.

The next act pits Socrates against Polus, a rhetorician promoting rhetoric as the path to power and happiness.

But the previous two acts are only warm-ups for the third, in which Callicles, a demagogue [i.e., democratic politician] on the make (515a), champions nature and the cause of the stronger over convention and the cause of the weaker. Callicles can see a role for Socrates' philosophy — as a child's plaything. Eventually, though, everyone has to grow up. And so the man of affairs, the only kind of "real" man, must cast toys aside and master the art of speaking, both to get ahead and to guard his rear. (Concordia Discors 127)

I think you'll find that the dialogue interrogates rhetoric, then Callicles' natural law hedonism (see further under "Speakers," below), in other words, subjects both to an incisive critique. It exemplifies, therefore, what we are calling critical thinking, though Plato's term for it would be elenchus. . .

Author

Athenian philosopher, writer, and founder of the Academy, Plato (lived 428-348 BCE), whose real name may have been Aristocles, "He of Noble Renown" (Plato = "broad"), was an Athenian aristocrat with an extremely distinguished family background and many connections to the Athenian elite.

Student of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle, Plato wrote voluminously on philosophy, and we're lucky to possess all his published work.

Work

Date, Setting, Background

While the composition of the dialogue has been dated to the earlier 380s BCE (Walker Rhetoric and Poetics p. 34), the dramatic date for it (when we're to imagine it happening) has to be 427 BCE, when Gorgias, the sophist from whom the dialogue takes its name, visited Athens and created a stir with his strikingly "Gorgianic" style of speaking.

While the composition of the dialogue has been dated to the earlier 380s BCE (Walker Rhetoric and Poetics p. 34), the dramatic date for it (when we're to imagine it happening) has to be 427 BCE, when Gorgias, the sophist from whom the dialogue takes its name, visited Athens and created a stir with his strikingly "Gorgianic" style of speaking.

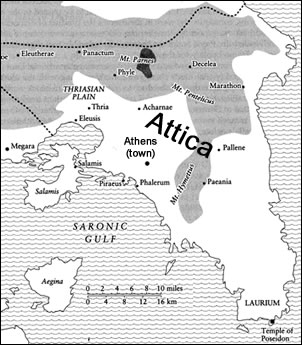

"The polis of the Athenians." The Athens of our dialogue was, and long remained, not a city within a much larger nation-state ("Greece" as a country didn't exist until the 1820s), but an independent "city-state," or polis, controlling territory known then and now as Attica (see map).

Thus when we speak of ancient Athens, though we often mean the municipality of Athens, in our class, we'll mostly be referring to the political entity known officially as "the polis of the Athenians," whose citizens included residents of the Attic countryside as well as of Athens-town itself. You can think of it this way: had Athens been named on the analogy of the US, you might have called it "The United Demes of Attica." But that's not what they called it. . . .

Anyway, all were Athenians, all took pride in their citizenship. And Athenian citizenship came before any local loyalty.

Anyway, all were Athenians, all took pride in their citizenship. And Athenian citizenship came before any local loyalty.

Athenian democracy. As to the constitution or form of government enjoyed by Athenians during this period, it is important to bear in mind that it was a democracy:

- A direct democracy, meaning that all enfranchised citizens (men only!) could, and to a large extent did, take part directly in legislative processes and governing generally

- That as opposed to a representative democracy like the United States.

- A radical democracy, meaning that the power exercised by the citizen body was not curtailed by property qualifications (e.g., voting rights only for the rich) or the like

- A speech-based democracy, meaning that citizens proposed and deliberated measures through the medium of public speech. Verbal persuasion, therefore, mattered very much!

Find out more by visiting Christopher W. Blackwell's "Introduction to Classical Athenian Democracy."

This period of the 420s can also be described as the high-water mark of the Athenian "demagogues," those democratic leaders, Cleon especially, much despised by elite writers like Thucydides and Aristophanes, whom we'll soon read. Callicles, Socrates' chief interlocutor in the dialogue, would, it seems, like to join their ranks.

As to the the dramatic situation, it is as follows: Gorgias, a famous sophist from the Sicilian city of Leontinoi, has just performed a "demonstration," or epideixis (remember that word!!), of his teaching at an unnamed Athenian's house.

Socrates, in company with Chaerephon, his close friend, has just shown up, too late, it seems, to have witnessed the epideixis. So it is decided that Socrates will have conversation with the distinguished visitor, who claims to be able to answer anything asked him, a claim Socrates puts to the test.

Form, Genre

Just a few words about form and genre. The work is in pure dialogue form, like a play, though it was surely meant to be read, not performed. Though characters in the dialogue were real people, the work itself should be regarded as a literary fiction.

As an author of prose dialogue, or of dialogue featuring Socrates, Plato was not the first. Verse comedy, most notably the Clouds by Aristophanes, had already made use of Socrates as a speaking character. Diogenes Laertius reports the tradition that a certain Simon the Shoemaker, one of Socrates' conversation partners, was the first to compose Socratic dialogues in prose (2.122-123). But the verbal agon or "debate," as developed in drama and the verbal dueling of the sophists (eristic), should also be understood as formative precursors.

Speakers

Our dialogue's speakers, most of whom, perhaps all of whom, were historical personages, are as follows:

Socrates, an Athenian philosopher (469-399 BCE), eventually put to death by the people of Athens. He wrote nothing except versions of Aesops' fables, and none of that survives. As for the historical Socrates' oral teaching, we can really only guess at it from the writings of his pupils, people like Plato, Xenophon, and Aeschines Socraticus. Socrates in this dialogue upholds philosophy.

Gorgias, (ca. 483-376 BCE) a professional teacher (a sophist) from Leontinoi in Sicily, and associated with a highly florid style of speech. It's 427 BCE, and Gorgias is visiting Athens on an embassy from his native city; while at Athens, he creates a sensation with his oratory. For more on his doctrines, writings, etc., click here. In this dialogue, Gorgias argues that rhetoric, mastery, in other words, of the art of persuasion, can endow those possessing it with impressive powers to influence actions and decisions, even beyond the powers of those possessing technical knowledge in various areas of expertise

Polus, pupil and protégé of Gorgias, he has accompanied his mentor on this embassy. Like his teacher, Polus is a Sicilian Greek (different city) and will become, if he isn't one already, a teacher of rhetoric. Polus, it seems, is younger than Socrates. Polus argues that rhetoric empowers speakers in ways capable of conferring great benefit on speakers themselves.

Callicles, an Athenian, and the only speaker whom we don't know about from other sources. Callicles, too, is a young man. He is an admirer of Gorgias and seeks to make his mark as a politician at Athens. Callicles, after concurring with Gorgias and Polus on the utility of rhetoric, and after putting philosophy down as, basically, a child's plaything, defends his natural-law hedonism, according to which the stronger, because stronger (and stronger = better, smarter), should enjoy greater pleasures, etc., indeed, should feel free to pursue self-indulgence without restraint.

Chaerephon, Athenian, and Socrates' very good friend, though not a thinker or writer in his own right. We'll see him again, as we will Socrates, in Aristophanes' Clouds.