Geography and Politics

The Mediterranean world, that is, the Mediterranean Sea and surrounding territory — Greece, Italy, Asia Minor, etc. — provide the setting for the stories that lie behind the plays we are reading. Greece is situated at the southern end of the Balkan peninsula; Greece and Asia Minor lie respectively to the west and east of the Aegean sea. Italy and Rome are west of that.

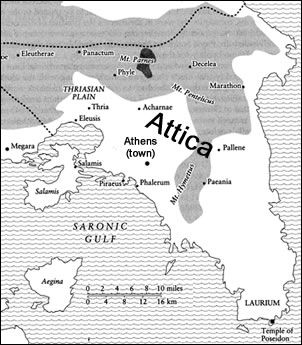

In ancient times, Greece proper, along with much of the remaining territory rimming the Aegean, was ethnically, linguistically, and culturally Greek. These territories formed no single political entity, but were divided up into a number of city-states, or (in Greek) poleis, each made up of an urban center and surrounding territory. For instance, the Athenian polis was a political entity controlling the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. (It is as if Binghamton and Broome County formed a separate and completely autonomous unit — no more NY state or USA.) For Rome, see just below.

Poleis were typically either democracies (rule by the people as a whole) or oligarchies (rule by the few). Tyranny counts as yet another form of government. Though the ancient sources vary in their use of the term tyranny (Greek turannis), it typically refers to some sort of an extra-constitutional dictatorship — rule by force rather than by law. Many Greek states (including Athens) were at various points ruled by tyrants. Finally, and related to the topic of tyranny, is the matter of stasis: civic instability, unrest, revolution. To the extent that Greek drama dealt with political issues (and it most certainly did), tyranny, stasis, indeed, political stability and legitimacy in general, figure prominently as themes.

Historical Background

We should think in terms of three periods: the Mycenaean age, the archaic period, the classical period, and the Imperial Period.

Mycenaean age/Bronze Age: From about 1600 to 1100 BCE, long before Greeks kept historical records or used alphabetic writing, a culture of palaces and kings flourished in Greece. The great cities included Mycenae, Tyrins, Thebes, Pylos, and (not as great as the preceding) Athens. These are also the great cities of Greek myth. For Greek mythology, to the extent that it has any factual basis at all (which it does to a very limited degree), is based on lore handed down by these prehistoric, "Bronze-Age" Greeks.

Archaic period: Some centuries after the fall of the Mycenaean kingdoms, Greece recovered and emerged into what we call the archaic (i.e., "old") period (approximately 800-475 BCE). This is the time when alphabetic writing, literature (written poetry, philosophy), and the Greek city-state first appeared. It is also a time when Greeks showed heightened interest in their legendary past. Greek colonization flourished during the archaic period, with Greeks settling the far-flung corners of the Mediterranean and Black Seas.

Classical period: 475-323 BCE was the time when democratic Athens and oligarchic-monarchical Sparta emerged as important powers and mutual adversaries. Ancient Greek drama, and in particular, the dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes, came into their own in Athens during the fifth century BCE, also the highpoint of Athenian democracy. The fifth century further sees the first history writing in Greek (Herodotus, Thucydides) and the heyday of the sophists, fee-charging teachers of rhetoric, argument, and other topics. The fourth century is the age of the philosophers Plato and Aristotle. Menander, writer of boy-meets-girl social comedy (New Comedy), comes to the fore at the end of the fourth century — the dawn of the Hellenistic period .

Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE): Crucial for Athens during the fifth century BCE was the crushing defeat and loss of empire suffered by the city as a consequence of the war it fought against enemies led by that other great power of Greece: Sparta. At first it looked as if Athens might prevail, at least insofar as it could preserve its empire, source of much of the city's wealth. But when Athens undertook an ill-conceived invasion of the island of Sicily, things took a decided turn for the worse. Tragedy will never allude to the war directly, but drama produced during the war simply cannot be considered in total isolation from it.

Finally, Imperial Rome. At its broadest, Roman history starts in the eight century BCE and continues into the fifteenth century CE ("of the common era," aka AD — our age). Rome began as a tiny hamlet ruled by kings in central Italy; by the first century CE, the Roman Republic (the kings had been thrown out) ruled an empire extending to much of the Mediterranean world. In 27 BCE, Augustus became the first emperor officially recognized as such by the Roman senate.

- Mythology. Rome had its own myths and legends: Trojan Aeneas as national ancestor, Romulus and Remus as city founders, and so on. But the background to Roman tragedy was largely Greek myth seen through Roman eyes. That even applies to a Roman history play like the Octavia.

- History and current events as themes. As in classical Athens, so under Imperial Rome, history and current events — who "we Romans" are, where "we Romans" come from — worked their way into drama. As we'll see, even Seneca's mythological plays (Phaedra, Thyestes) can be read as meditations on the situation at Rome. For Seneca, that situation was largely defined by the reigns of two emperors: Claudius (41-54) and Nero (54-68). Seneca regarded the first as a cruel tyrant. The second, for whom Seneca had high hopes, eventually proved an even more cruel tyrant than his predecessor; more on the Seneca Phaedra study guide.

Ancient Greek (and Roman) Religion, Myth

Greece and Rome became predominantly Christian starting about 500 CE (CE, "common era," i.e., after the time of Christ). But in ancient (i.e., pre-500s CE) times, Greeks and Romans were polytheistic, that is, they worshiped many gods. Religion was less about faith or theology or good deeds than about human-divine reciprocity. For the gods were expected to protect human beings and provide for their needs in exchange for sacrifice, the killing of animals offered as gifts. But stories grew up around these gods and their human offspring, the stories that made up what we call "Greek mythology." These myths form the basis of a great many — though certainly not all — of the plots of ancient Greek and Roman drama.

Unlike the great religions of modern times, ancient polytheism did not necessarily assume that its gods were paragons of moral excellence. The gods of myth exhibit the same foibles as mortal humans, only on a grander scale. Indeed, students are sometimes shocked by the imperfections of the immortals, as were certain Greeks (e.g., Plato) already in ancient times. Still, tragedy often seeks to get beyond traditional notions of Zeus' and other gods' misbehavior. Hence the somewhat halting movement in the ancient tragedies toward a transcendent moral theology, as in the tragedies of Aeschylus — but contrast that with the morally ambiguous gods of Euripides.

Interestingly, Greek mythology, with name-changes for the gods, forms the backbone of Roman mythology.

Here follow thumbnails of the principal gods and heroes/heroines of ancient Greek and Roman myth and legend:

Gods

- Zeus (aka Cronos' son, Roman Jupiter): King of the gods and lord of the universe, he rules from Mount Olympus, home of the gods. Cheating frequently on his wife and sister Hera, he fathers many heroes and heroines by mortal mothers

- Hera (Roman Juno): Zeus' sister and wife. Zeus' girlfriends at times run afoul of her jealousy

- Athena (aka Pallas, Roman Minerva): Zeus' virgin daughter and right-hand woman. She is a powerful warrior and the patron goddess of Athens

- Apollo (aka Phoibos, Paian, Loxias, = Roman Apollo, Phoebus): Youthful god of prophecy, healing, and light, brother of Artemis, protector of adolescents, and lord of Delphi ("rocky Pytho"), where the Pythia (Apollo's priestess) was his prophetic mouthpiece. The Delphic oracle, located at Delphi (see picture at right), is very important in tragedy

- Loxias = Apollo as god of prophecy

- Paean/Paian = Apollo as god of healing

- Pythian = Apollo as god of Delphi

- Hermes (Roman Mercury): Messenger god, god of speech, god of travelers, divine guide, god of thieves, Hermes is the ambiguous trickster god

- Artemis(Roman Diana): Apollo's virgin sister, protector of adolescents, and goddess of the wilds and of the hunt

- Aphrodite (aka Cypris, Cypria, "the Cyprian" = Roman Venus): Goddess of beauty and sex (eros), she plays an important role in Greek myths and Greek tragedy

- Hephaestus (Roman Vulcan): Patron of artisans and god of the forge

- Ares (Roman Mars): The god of violent, sorrowful war. Contrast Athena, the goddess of honorable, defensive war

- Dionysus (aka Bakkhos, Bromios "Bellower," Bull etc., = Roman Bacchus, Liber): The god of wine, drunkenness, ecstasy, fertility. Also, the patron of Greek drama

Some Heroines and Heroes

- Heracles (Roman Hercules): Son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the greatest of the heroes

- Atreus, father of Agamemnon and Menelaus and brother of Thyestes, with whom he contended for the throne of Argos. Atreus notoriously tricked his brother into eating a stew made from the flesh of his brother's sons — the "Feast of Thyestes"

- Agamemnon (an Atreid = "son of Atreus"): King of Argos, husband of Clytemnestra, brother of Menelaus, and commander-in-chief at Troy

- Menelaus (an Atreid = "son of Atreus"): King of Sparta, brother of Agamemnon, and husband of Helen

- Helen: Daughter of Zeus and Leda, sister (1/2 sister?) of Clytemnestra, wife of Menelaus, and lover of Paris. Renowned as the most beautiful of all mortal women

- Clytemnestra: Sister (1/2 sister?) of Helen, wife of Agamemnon, mother of Iphigenia

- Iphigenia: Daughter of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and a key figure in the launching of the Greek expedition against Troy

- Orestes: Son and avenger of Agamemnon, also brother of Iphigenia and Electra

- Electra: Daughter and avenger of Agamemnon, also sister of Iphigenia and Orestes

- Odysseus (Roman Ulysses): The cleverest of the Greeks, and a war-leader at Troy

- Achilles: The greatest and bravest of the Greek warriors at Troy

- Oedipus: King of Thebes, he is husband to his mother and murderer of his father

- Antigone: Daughter-sister of Oedipus, and princess of Thebes

- Jason: Faithless husband of Medea, he voyages far to get the Golden Fleece

- Medea: A barbaric princess and wife of Jason, she helps him get the Golden Fleece

- Theseus. An Athenian hero and king of Athens, Theseus was the father of Hippolytus and husband of Phaedra

The Trojan War

Many of the stories that make up Greek mythology center around the Trojan War, the 10-year conflict in which Greeks under Agamemnon destroyed the city of Troy in Asia Minor — that as revenge for the theft of Helen by Paris, a Trojan prince.

The Trojan war is the legendary event that famously sent countless heroes, including the peerless Achilles, to an early grave. Even many of those who survived the war died soon after its conclusion — notably, Agamemnon.

Among the dramas stemming from the Trojan War cycle are the tragedies that make up the Oresteia by Aeschylus. Another Trojan War-related drama is Euripides' Iphigenia at Aulis.

The Theban Cycle

The city of Thebes, located not too far from Athens (see the map at top), was also the epicenter of legends important for the dramatists. The sorrows of Oedipus, king of Thebes, form but part of a cycle in which the city, its rulers, and its citizens suffer as a consequence of horrific sins (fratricide, incest, etc. etc.) committed by various great personages of the city. Rather like Asian Troy, the Greek city of Thebes is eventually destroyed by a band of allied war-leaders, but only after a failed prior effort and the tragic events (Sophocles' Antigone) stemming from that.

Jason and the Golden Fleece

Other tales have to do with Jason's voyage in quest of the Golden Fleece. Sailing with his companions to the easternmost shore of the Black Sea, Jason wins the Fleece with the aid of Medea, a barbarian princess and enchantress. Euripides' Medea is based on Jason's and Medea's parting of ways back in Greece.