The following represents a mix of ancient Greek, Latin, and modern English technical terms pertinent to this course. Many of them will figure on quizzes, in discussions, and so on. I will add to this as occasion demands.

Terms in Greek or Latin are italicized. Note that Greek and Latin plurals don't always conform to English usage.

act. From Latin, actus. By Seneca's time, Roman tragedy in Latin was typically divided into five acts, with choruses separating those acts. This act structure did not necessarily correspond to the dramatic-thematic divisions of Senecan plays; see Senecan schema.

agon. In Greek drama, an on-stage debate scene, one often modeled after courtroom or political debate, between two characters.

amoibaion. In Greek drama, amoibaion is choral dialogue, i.e., antiphonal song involving a character and the chorus.

alastor. Greek: a spirit of revenge, sort of like a masculine version of one of the Furies. Oedipus sort of becomes one in the Oedipus at Colonus.

anagnorisis. Greek, "recognition." By "recognition," Aristotle basically means the discovery of one's own or another's true identity, thus a "change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune" (p. 72). For Aristotle, recognition is one of two elements (the other being reversal) necessary to the best sort of tragic plot. But Aristotle's notion of recognition can also blend in with a higher self-knowledge in terms of a character's recognizing and coming to terms with her/his fate, as in the case of Oedipus. Still, the more precise term for that is tragic knowing, or pathei mathos.

"ancient law of hubris and ate," aka "tragic formula." C. J. Herington, in his book on Aeschylus (1986), discusses what he calls the "ancient law of hubris and ate." Less a law than a worldview, it reflects a poetic-mythic understanding of human excess as subject to cosmic-divine forces seeking to re-balance those excesses. You can think of that as a kind of archaic Greek precursor to the Aristotelian notion of tragic reversal (peripeteia).

Here follow the elements of that "law," with a fourth element tacked on at the end Important to note is that we should not approach 1 through 4 below as some sort of linear causation string, a kind of tragic checklist. Rather, it all represents a constellation of inextricably linked states, each always already implied by the other:

- Koros, excessive wealth, power, good fortune, etc. such as can breed:

- Hubris, errant disregard (evidenced through word or deed) for the rights, status, etc. of another (mortal or god) whose rights, status, etc. matter. That can — and in Greek tragedy, typically does — take the form of a violent act necessitating some sort of countervailing violence.

- Ate, the delusion that enfolds us when we commit acts that must lead to our ruin. Alternatively, the word refers to ruin itself.

- Dike, "justice," understood here either as the process correcting for that which has grown "unduly great," or else as the ideal of a balanced human or universal order, and thus the justification for tragic action. Which calls into question whether tragic justice is truly "just"? Do the ends justify the means? Does the punishment fit the crime?

archon. Greek word for "official" or "magistrate." At Athens, one of nine chief officials.

Areopagus. He boule he tou areiou pagou, "The Council of the Hill of Ares," AKA the Areopagus Council, originally functioned as the aristocratic "upper house" of the Athenian state in the early archaic period. By Solon's time its legislative functions were largely replaced by the new council (boule) of the 400. In 461, its oversight (veto power?) over assembly decrees seems to have been removed completely. After that point, it had oversight over certain murder trials (intentional homicide) and other things (mistreatment of the sacred olive trees). In Aeschylus' Eumenides, the "Hill of Ares" provides the setting for the trial scene. The jury that Athena impanels for that trial is to be imagined as the creation of the Areopagus Council.

ate. Greek for "delusion" or "ruin." In Greek tragedy, the two are virtually the same thing. See also "ancient law of hubris and ate."

associative poetics. Much in evidence in Aeschylus, it's the juxtaposition of dramatic action (whether action prior to drama on stage or part of that drama) with dramatic action, dramatic theme with dramatic theme, poetic image with poetic image, based often on only a limited number of shared elements — sort of like the way that thought of one thing can remind you of another thing.

EXAMPLE. The fire signals in Aeschylus' Agamemnon convey the news of Troy's fall from Troy itself to Argos. But they do more. The fire itself connotes destruction, and the red color of the fire connotes killing. Thus the very image of fire poetically "communicates," or associates, the destruction and killing at Troy with what is to take place at Argos. The red "welcome" carpet functions similarly. The imagery of the signals and carpet poetically associates the doom awaiting Agamemnon with earlier crime (hubris) in which he is involved or implicated: the murder of Iphigenia, the impious violation of temples during the destruction of Troy.

bacchanal. Can refer to a female worshiper of Dionysus (as such translates Greek bakkhē) or to a Dionysian revel.

bacchant. Same as bakkhē.

bakkhē. Female worshiper of Dionysus. A male worshiper would be called a bakkhos.) The term comes from the cry, Io bakkhe! A male worshiper would be called a bakkhos. Bakkhos (often written as as "Bacchus") is also a name of the god himself.

blood-guilt. In tragedy, the very special crime of killing someone related to oneself by blood.

Bromios (Bromius). A name (Greek) for Dionysus.

catharsis, katharsis. Greek, "cleansing," "purification," "purgation." According to Aristotle, a tragic audience member's experience of pity and fear produces a catharsis, a "cleansing" of those emotions from the psyche. But what exactly is meant by that remains somewhat mysterious.

choregia, choregus. At Athens, the choregia was a duty imposed by the state on a wealthy citizen. Designated a choregus, his job was to fund and organize the production of drama or dithyramb at a dramatic festival. If his chorus (i.e., production) won, he would receive special recognition.

chorus. See khoros.

City Dionysia. See "Dionysia."

closet drama is drama composed not for the stage but to be read to oneself or perhaps recited/performed at a private gathering. Scholars debate whether (Pseudo-)Senecan tragedy was closet drama; see more on the Seneca Phaedra study guide.

coryphaeus. The "chorus leader," that particular chorus member whose job during episodes (dialogue sections) is to participate in dialogue with speaking characters or to insert brief comments into dialogue between characters.

crepidata. I.e., fabula crepidata, one of several genres of Roman drama, named from the crepida, the Latin word for the soft boot worn by actors performing Greek tragedy. Crepidatae (plural of crepidata) were tragic plays adapted and/or translated from Greek originals and on Greek-mythological subjects, for instance, Accius' Bacchae (compare Euripides' Bacchae) or Seneca's Phaedra, which retells the basic Phaedra-Hippolytus myth, and suggests debts to plays by Euripides. (Romans, though, did not regularly use the term crepidata; they preferred tragoediae, i.e., "tragedies.") See more on the Roman Tragedy, Introduction study guide.

cultural translation. By "cultural translation" I mean the transference of a narrative (a myth), a theme, a motif, a genre (e.g., tragedy) from a source-culture to a destination-culture, say, the Oedipus-Antigone-etc. myth as originally handled in Greek sources like Sophocles' "Theban plays," and the same, basic narrative as handled in another time and place, say, World-War-Two France (Anouilh's Antigone). That will, I suggest, at some level involve an element of translation, literally, "carrying over" ("translation" from Latin trans-"across" and latus-"carried"), for instance, of a basic story line or myth-pattern.

So translation necessarily involves continuities, a re-framing that preserves key elements of the old in the new. But just as translation from one language to another necessarily produces transformation, so, too, in cultural translation, the end-product as a whole is, at some level, something altogether different.

The question then becomes, how is it different? Is the new cultural framing like a different lens revealing hitherto unseen facets of the "translated" object? Or does the re framing involve transformation going to the very core of the object in question — to its essence?

Those are the kinds of "translations" we're principally concerned with in our course as we examine a genre — tragedy — "translated" from a classical-Athenian mode of handling to a Roman to a modern. . . .

curiositas. Defined as "excessive eagerness for knowledge, inquisitiveness, curiosity" (Oxford Latin Dictionary), curiositas is the quality of being curiosus; we can think of it as the "invasive gaze." In Petronius' Satyricon, one of the characters peers through a keyhole to witness a shocking sex act. Her eye is described in Latin as curiosus (curiosum oculum, 26.4), and it is, among other things, this voyeuristic excess that concerns us in our study of Senecan tragedy. Take, for instance, Seneca's Phaedra, specifically, the Act Four Messenger's speech describing Hippolytus' chariot accident, death, and dismemberment. For gory detail, it goes beyond the corresponding speech in Euripides' Hippolytus — does that tell us anything? Carlin Barton, addressing the seeming paradox of austerely moral Romans fascinated by excess, writes, "It is not surprising that Seneca [stoic in all senses of the word] imagines his severe and celibate Hippolytus dying in an orgy of erotic violence. . ." (Sorrows of the Ancient Romans, p. 76). Does, then, the Roman playwright's attempt to appeal to what he seems to suppose is his audience's interest in the grotesque and extreme tell us something about Senecan tragedy? See also "fascination," "perverse exaggeration."

Delphi, Delphic Oracle. Delphi, a Greek city about two hours west of Athens by car or bus, was where Apollo had his most famous oracle, or place of prophecy. (The word "oracle" can also refer to any prophecy given by the god.) At Delphi, worshipers, after purifying themselves, would pose questions to the god's priests. The Pythia (from Putho, another name for Delphi), that is, the priestess of Apollo, would then serve as the god's mouthpiece in responding to the question. Note that the Delphic Oracle and its prophecies loom large in ancient tragedy. Note also the two most famous sayings, the most famous in all Greek, inscribed on Apollo's temple at Delphi:

- "Know thyself!"

- "Nothing to excess!"

desis. Aristotle's term for "complication," the problem that tragic action seeks to resolve.

deus ex machina. Latin for, literally, "god from the machine/crane" (in Greek, mekhane), meaning the practice of lowering a god by crane down to the stage for the purpose of intervening in the action of a play. Hence its use as a term of literary criticism, where it means any artificial device or contrived plot turn designed bring about an otherwise improbable or impossible resolution to a plot complication.

dike. Greek for "justice," in Greek drama especially as a higher principle guiding human destiny. See also "ancient law of hubris and ate."

Dionysia. In Greek, Dionusia is a plural noun; it refers to any festival honoring the god Dionysus, for instance, the. . .

Greater Dionysia, aka City Dionysia, at Athens, the principal festival of the god. Founded by the tyrant Peisistratus (ruled off and on 561-527 BCE) and modeled on traditional Dionysian festivals celebrated in the countryside, it involved competitive performances of choral/dramatic poetry in the form of tragedy, satyr drama, comedy, and dithyramb. It took place in late March.; Non-Athenians participated in it and could attend performances, which took place in the Theater of Dionysus

Rural Dionysia. A group of festivals happening in the Athenian countryside during the month of December. Often involved competitive dramatic performances, though the main event seems to have been the phallic procession

Lenaea. Very old festival, held in February/March, and with dramatic competitions, from lenai, yet another name for female worshipers of Dionysus. From at least about 440 BCE on, performances were held in the theater of Dionysus. We know that tragedies and comedies were performed during it

Dionysus. Son of Zeus and Semele, a mortal woman. God of wine, revelry, drama, etc. Aka Bacchus (Bakkhos), Bromios ("Roarer"), "The Bull," Iacchus. He was called "The Twice Born" (dithurambos) because he was born once from his mother, once from Zeus' thigh.

dithyramb. In ancient Greece, choral poems originally honoring the god Dionysus. Dithyrambic choruses at the Athenian Greater Dionysia consisted of 50 boys or men dancing and singing in a circle.

ekkuklema. Greek for "stage trolley." In Athenian drama, the ekkuklema was used to roll corpses or other out onto the stage in order to reveal an indoor scene or tableau.

empyrosis (em-peer-OH-sis). A Stoic concept or motif, empyrosis is the cosmic fire that will end this universe, from whose ashes will emerge a new one. To quote the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "The Stoics hold that the cosmos goes through a cycle of endless recurrence with periods of conflagration, a state in which all is fire, and periods of cosmic order, with the world as we experience it (Nemesius, 52C)." Roman playwrights, notably, the author of the Ocatvia (see there Seneca's speeches) associate this Stoic idea of a world destroyed by fire with that of decline leading to destruction and rebirth.

episode, epeisodion. Greek epeisodion means "additional entry" or "episode." Where Greek tragedy is concerned, an episode is any section of a play following the entry of the chorus (parodos), coming between stasimon choruses, and featuring dialogue between actors or between actors and chorus leader.

eponymous archon. At Athens, an official whose duties included overseeing the selection of finalists in dramatic competitions.

Erinys (plural, Erinyes). Translated as "Furies," (Latin Furiae) the Erinyes, daughters of night and associated with the Underworld (the world of death), were the ancient Greek goddesses of punishment. In tragedy, they can be thought of as springing up up to drive killers of blood relatives made with guilt.

eros. "Love," "desire," "lust," sexual or otherwise (greed, hunger, ambition, etc.), often overpowering, often irrational, often disastrous. Capitalized, "Eros" refers to the god of love/lust.

essentialism. The idea that a category can describe some fundamental core truth about a class of things, such that the category itself might as well be a real thing in its own right. Take "chair." The word "chair" can correctly be applied to any number of chairs out there, but is there some core essence shared by all chairs, such that they are all chairs before they are anything else? If we choose to think so, that is essentialism.

Think now of tragedy. There are any number of tragedies out there, but is it right to understand "the tragic" as a core, essential element of all tragedy? Or should we use the word "tragedy" to help us consider similarities and differences between dramas we study, though without making assumptions that there is that special something without which no tragedy is tragic?

Eumenides. The word "Eumenides," the "Kindly Ones" (i.e., those who we wish were kindly, though we fear them greatly), serves both as a title of one of Aeschylus' plays and as an alternative name of the Furies. It appears in Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus, though not in Aeschylus' Eumenides.

exodos. The finale and choral "exit song" of an ancient Greek drama.

ethos. "Character," not in the sense of a dramatic character or role (Antigone, Oedipus), but of a dramatized personage's inner motivations, especially as that relates to her or his moral goodness or badness. "Character reveals moral purpose," says Aristotle (p. 64).

fabula. Fabula is Latin for "story," "myth," "fable," "play." For the two genres of fabula (Roman play) that we're concerned with, see:

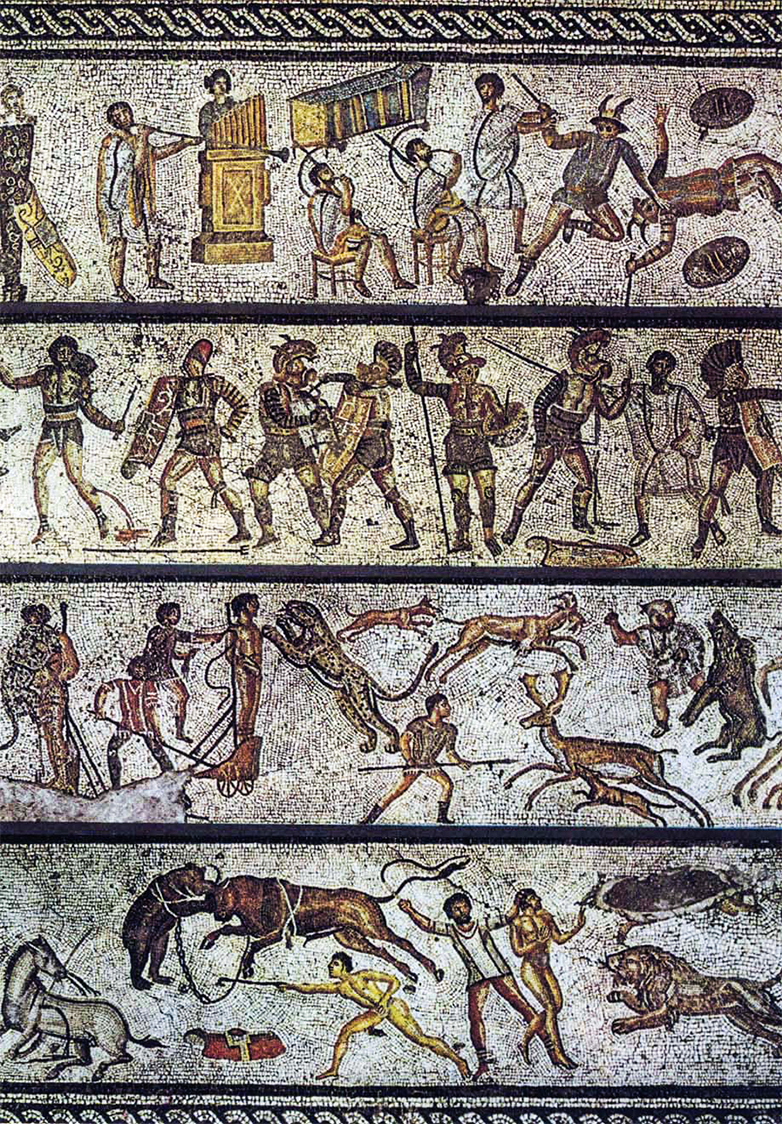

fascinatio, fascination, fascinum. As a feature of Roman culture, fascination (Latin, fascinatio) is more than heightened interest in something. It is that inability to look away when presented with something intriguing, shocking, bizarre, or uncanny. Latin fascinatio comes from fascinum, meaning a phallic shaped pendant or charm used to "fascinate" ("stupefy," "entrance"), and thereby neutralize, the evil eye. Carlin Barton (Sorrows of the Ancient Romans) associates fascinatio with curiositas, the urge to gaze upon what is outsized, misshapen, grotesque, violent. (As such, fascinatio is, arguably, related to the rhetorical phenomenon that I call "perverse exaggeration.") For Barton, gladiators, entertainer-athletes specializing in the game of death, as objects of contempt and admiration, longing and disgust, sum up all the contradictions inhering in fascinatio and curiositas. My question is whether fascinatio and curiositas help explain Senecan tragedy, and if so, how.

Greater Dionysia. See "Dionysia."

hamartia. Greek, "error," "mistake," "transgression." DOES NOT MEAN FLAW! The hamartia of a noble or lofty character is always what sets tragic action in motion.

heros. Greek word from which the word "hero." In ancient Greek religion, a heros was a deified spirit of a dead person, often understood as capable of protecting (or harming) the living. Oedipus becomes one in Oedipus at Colonus.

hubris/hybris (noun), hubristic (adjective). Greek: "insult," "arrogance," "insolence," "outrageous or humiliating treatment." In high school English class we're told that hubris is "pride." Well, not exactly. In classical Athens, hubris was any word or action infringing on the dignity of another: dissing someone, hitting them in public, and so on. The problem wasn't that it made the victim feel bad. It was that it diminished the worth of the victim in the eyes of others, the only remedy being retaliation. In Aeschylus' Persians, Xerxes' pontoon bridge connecting Asia with Europe is hubris because it violates the order established by the gods; as such, it offends them. The tyrants of Greek tragedy (Creon, Oedipus) are notoriously hubristic. See also "tragic formula."

hupokrites. Greek, literally, "answerer." It meant, though, "actor."

Iacchus. Greek, "He of the cry, Io! " I.e., Dionysus.

ideal type. Ideal type is not perfect type: the perfect student, martini, etc. Rather, an ideal type (in German, Idealtypus, an analytical concept invented by Max Weber, twentieth-century German sociologist) is "ideal" in the sense that it is an intellectual construct (it represents an idea of something, not an actual thing) mapping out key features of a category or classification (pizza, tragedy) by virtue of which individual instances merit being categorized as such — what it is, in other words, that makes a pizza pizza, what the essence of pizza is. We assemble that knowledge by studying instances (going to lots of restaurants, learning to recognize shared features of a range of clearly related things we'll start calling pizzas) and deducing from the knowledge thereby gained an idea of the essence of pizza. With that knowledge, we can then speak more insightfully of various pizzas and pizza-like things we encounter in the world. (Is stuffed pizza pizza? Why or why not?)

Similarly, what is the essence of tragedy? What gives value to any idea we form of what tragedy is? And how does that idea of what tragedy is help us evaluate individual instances of, and variations on, the genre?

interruption. See the Bonnie Honig assignment.

io bakkhe! One the cries characteristic of the worship of Dionysus.

khorēgia, khorēgos. Literally, "chorus guidance/leadership," the khorēgia had nothing to do with being a chorus director. Rather, it was the public imposed duty or "liturgy" of paying for and (secondarily) organizing dramatic or dithyrambic productions. The producer-financier was the khorēgos. In classical Athens (ca. 500-ca. 300 BCE), an official called the King Archon imposed this very expensive office on men of the very wealthiest class. If you were a khorēgos and your production won a prize, you won that prize. The wealthy tended not to welcome being selected, but if selected, would spend lavishly.

khoros. Greek: "dance," "group of dancer-singers," i.e., a "chorus." The word could also refer to a dramatic production. Thus if a playwright in Athens were to be awarded a chorus, that meant he'd be able to have a play of his staged.

katharsis. See catharsis.

komast. In Greek, komastes. Male performer of/participant in a Greek komos. The early pictorial evidence shows them as dancers, often in costume, sometimes grotesquely padded. (Padded costuming later associated with comedy.)

komoidia. Greek for "comedy," the word means literally "revel song."

komos. Greek, pl. komoi. Evidently root of the word "comedy," in Greek, komoidia or "komos song," komos itself was:

- A drunken revel or procession, whether organized or impromptu.

- According to Aristotle (Poetics), word derived from kome, "country district." Komasts (participants in komoi) were, according to Aristotle, disgraced, proto-comic performers forced to wander country districts.

- On a mid-400s BCE inscription at Athens, the word for dramas (tragedies and comedies) performed in honor of Dionysus.

kommos. Not to be confused with a komos-"revel," the word kommos (two "m"s) comes from a root meaning to strike, i.e., to strike one's breast in lamentation. In Greek tragedy, a kommos is a sung lamentation scene featuring dialogue between a main character and the chorus.

koros. In Greek, koros refers to a state of "plenty" or "excess," whether of wealth, power, pleasure, or similar. In Greek tragedy and other poetry, koros can be imagined as a state of plenty such as can induce arrogance (hubris) and crime. See also "tragic formula."

Lenaea. See "Dionysia."

libation. A "libation" is a drink offering — often, though not always, of wine — to a god or to the dead. The liquid is poured on the ground, floor, or altar. At ancient Greek drinking parties, it was customary to offer three libations to three gods, the third being to "Zeus the Savior."

In Aeschylus' Oresteia, the blood libation figures prominently as a an image/motif.

lusis. Aristotle's term for "resolution," in tragedy, the untangling, usually through peripeteia, "reversal," of some plot complication.

maenad. Female worshiper of Dionysus.

mekhane. In Greek, any stage "machine," especially the crane used to lower gods to the stage. The Latin term deus ex machina, "god from the machine," refers to just that.

messenger speech. One of the chief features of ancient Greco-Roman tragedy, messenger speeches feature a character, often referred to simply as "Messenger," describing events offstage. That may seem undramatic, but the narratives can be vividly descriptive and suspenseful, and often focus on battles, violence, suicide, etc. It was, in fact, a convention of ancient Greco-Roman tragedy that violent action not be depicted on stage, but narrated after the fact. (There are exceptions to the no-violence-on-stage pattern, for instance, Phaedra's suicide in Seneca's Phaedra, though scholars debate whether Senecan tragedy ever would have been staged. In Sophocles' Ajax, the title character's suicide will have been viewed by spectators in the Theater of Dionysus.)

Messenger speeches thus offer playwrights the opportunity to display skill in vivid narrative and to flex their poetic-rhetorical muscle. But the events they narrate are always crucial to the story. Still, messengers, as on-stage presences, at times seem to play a role confined to delivering the message, with no characterization beyond that: no name, no history, no anything. Other messengers, like the Herald in Aeschylus' Agamemnon, have an investment of some sort in the stories they tell and in the dramatic situation. Still others play a key role in the action. In Aeschylus' Libation Bearers, Orestes, pretending to be someone else, tells Clytemnestra, his mother, the news of his — Orestes' — supposed death. The story is false, but his is still a kind of messenger speech, one integral to deception making possible the killing of Clytemnestra and of her lover, Aegisthus.

mimesis. Greek, = "imitation," it's the principal concern of Aristotle's and others' theories of tragedy, literature, art generally.

mos maiorum. Latin for, literally, the "way of the ancestors," this is an important Roman concept referring to an idealized past when Roman men and women lived that values that Rome was supposed to be about: courage, restrain, honor, patriotic self-sacrifice. Often, it was held up in contrast to a (supposedly) decadent present, for instance, to remind young people of the ideals they were to live up to. As presented by the trope of decline, the days of the ancestors were a kind of mythic golden age with which "we" have lost touch but could revive if only we could live in accordance with their ways.

muthos. Greek: myth, story, plot. Aristotle uses the word to mean "plot," i.e., the action of a story or drama.

nominalism. I.e., categories as mere names, not realities in themselves. Nominalism is the philosophical position that categories are merely conventional labels, not names of actual things apart from the instances collected in a category. The concept matters for our course because we'd like to know if, on the one hand, the "tragic" represents a core essence at the hear of any given tragedy (realism), or if instead the definition of tragic genre needs to be flexible, needs to treated be a way gaining a better purchase on things called "tragedies," and not as an immutable reality in its own right.

nurses. In Greek, trophos, in Latin, nutrix. Nurses in ancient Greek and Roman culture were servants tasked with feeding and otherwise tending to the needs of the babies and small children of elite personages. In tragedy, the children are grown, and their nurses are tasked with other duties. Cilissa in Aeschylus' Libation Bearers is the former nurse of Orestes and participates in the deception of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. In Euripides (e.g., Medea) and in Roman tragedy (Seneca Phaedra, Pseudo-Seneca Octavia), nurses continue to serve those whom they once cared for. As confidants, they are capable of giving good advice but may feel forced to give bad advice to save themselves and their employers. They are not themselves tragic characters but they often enable tragic action.

omophagia. Greek, "raw flesh eating." Sometimes attributed to Dionysus worship, it is not clear that this was ever actually done. See also sparagmos.

orkhestra. Dancing area in front of the stage of a Greek theater.

parodos. Either (1) "side path" through which performers would pass when entering or exiting the performing area of a Greek theater from either side, or (2) the "entry song" of the chorus in a classical Athenian drama.

parody, parodic, paratragedy, paratragic. Parody can be defined as "A literary composition modeled on and imitating another work, esp. a composition in which the characteristic style and themes of a particular author or genre are satirized by being applied to inappropriate or unlikely subjects, or are otherwise exaggerated for comic effect" (OED).

Thus we can think of styles that parody tragedy without actually being it, that is, that imitate it outside a noticeably tragic context, and do so with some sort of artistic point, perhaps comic and satiric, as per OED definition.

Styles of discourse parodying tragedy we call paratragic. Paratragedy is mostly associated with comic discourse aping the elevated and often emotive language of tragedy — think of a small-time crook trying to sound like Shakespeare.

But it can also be argued that paratragedy shows up in satyr drama, too, which resembles both tragedy and comedy without quite being either.

pathei mathos. A phrase used by the chorus in Aeschylus' Agamemnon, it refers to tragic knowing, or more literally, "learning through suffering." In Greek tragedy, characters often "learn through suffering," though sometimes they learn too late.

peripeteia. Greek, "reversal," according to Aristotle, that point in the plot of a tragedy when the fortunes of a character change from good to bad or vice versa.

perverse exaggeration. By "perverse exaggeration," I mean a rhetorical figure fairly typical of Senecan and Pseudo-Senecan tragedy: that of taking a sentiment, finding its potential to express something over the top, outrageous, or similar, and then exploiting that potential for all its worth. Take, for instance, a made up example like the following: "STUDENT: Professor Snape, do you really hate students? SNAPE: Hate students? I love them! I love to eat them, crunch them, munch and lunch on them!" Well, no, he doesn't, but still, an example of rhetorical exaggeration involving lurid imagery and extravagant language.

Turning now to examples from our reading, I think we see something resembling perverse exaggeration — maybe not it, but approaching it — in Euripides' Alcestis, specifically, the scene where Alcestis and Admetus first come on stage to express their grief (she's about to die) in extravagant and, one might say, performative ways. Perverse exaggeration will have been a rhetorical mode that, arguably, found a ready audience among Romans, who, taken as a whole, seem to have felt a certain fascination with the extreme and the grotesque. For more, see PowerPoints for Senecan and Pseudo-Senecan plays.

phallus/phallos. In terms of costuming, a representation, often grotesquely exaggerated, of the male sexual organ.

phallus pole. In Greece, during Dionysian processions, a tree-trunk representing a phallus and carried usually by costumed revelers.

pollution. Ritual pollution refers to the supernatural stain or blot left on one through any of the following:

- sex

- childbirth

- menstruation

- homicide

Typically, those carrying pollution with them could not enter into sacred enclosures — temples and such. Before they might do so, they needed to be purified. Those marked as killers of men or women posed a danger to others in that they were regarded marked by the gods for destruction. Oedipus brings curse and pollution to Thebes because of his past acts.

praetexta. I.e., fabula praetexta, a genre of Roman genre, named for the toga praetexta, a garment worn by Roman high officials on ceremonial occasions. Praetextae (plural of praetexta) were plays on Roman historical (or at times legendary-historical) topics. Early praetextae (by which I mean mostly the period of the 100s BCE) very often seem to have treated an act of heroism by a recently deceased personage; as such, they seem to have played an important in the Funeral celebrations of "great men" (for instance, Marcus Claudius Marcellus' victory in single combat with the Gallic chieftain, Viridomarus, in 222 BCE, an event commemorated in Naevius' Clastidium). But they also could treat events from the early, and mostly legendary, history of Rome, as, for instance, in a play like Accius' Brutus, which told the story of the Republic's foundation. See more on the Roman Tragedy, Introduction and Octavia study guides.

Principate is the word for phase one, 27 BCE-284 CE, of the rule of emperors in ancient Rome. The term "Principate" derives from the fact that early on, the emperor modestly-ironically would call himself (among other things) princeps, "first citizen," in an attempt to avoid the title "king," a word hateful to Roman sensibilities ever since the expulsion of Rome's kings near the beginning of its history. This period, that of the Principate, matters to us because it saw the composition of (Pseudo-)Senecan tragedy (mid first century CE to ca. 100) and relates to political themes in same, especially, that of just rulership versus tyranny. See also the "Roman Tragedy, Introduction" study guide.

prosatyric. The label "prosatyric," meaning "standing in place of a satyr drama," is often used for Euripides' Alcestis (a) because it, ostensibly, a tragedy, was fourth in its tetralogy (the place usually assigned to satyr drama), and (b) because aspects of it resemble satyr drama and comedy, a fact already noticed in antiquity. See more on the Alcestis study guide and PowerPoint.

proagon. At Athens, before a dramatic contest was to take place, each competing dramatist would advertise his production by presenting his cast before the public and saying a few words in the proagon.

prologue, prologos. Prologos, in Greek, literally "pre-speech" or "pre-speaker." Where ancient Greek or Roman drama is concerned, "prologue" can carry any of the following, related meanings:

- That section of a play preceding chorus's entry song, the parodos

- A speech or speeches at or near the very beginning of a play, and devoted to establishing situation, providing background, etc. In Euripides, such prologues are frequent and are at times spoken by a character whose sole function in the play is that, e.g., Aphrodite in the beginning of Hippolytus

- The speaker of such a prologue

realism. The philosophical position that names of categories (as opposed to of individual things) are names of real things. The concept matters for our course because one way to understand genre is as some sort of an essence inherent in a genre like tragedy. So, is there some essential something at the core of tragic drama, and therefore any individual drama worthy of the name tragedy? If so, what is it?

Republic. The term comes from res publica, the Roman "public thing," i.e., the state, but we'll use it to refer to the period ca. 510-27 BCE, when Rome was free from monarchy and ruled by the Roman Senate, elected officials, and the people. Though the Roman Republic was in some ways democratic, it was mostly an oligarchy, i.e., ruled by the elite few.

rhetoric. Before you go further with this entry, you might want to look up these term entries, which take a deeper five into aspects of rhetoric important to us:

Rhetoric can, very generally, be defined as the use of language, spoken or written, for purposes of social outreach: to forge connections with others and to shape their perception of reality. Call that type A rhetoric. Under that definition, language pretty much always has a rhetorical dimension. And that's helpful, as it allows us to explore the "rhetorical," that is, the social-communicative, side of all kinds of utterance, formal or informal, spoken or written, prose or poetry.

Particularly helpful to us will be another, more narrowly technical definition of rhetoric as "the art of using language effectively so as to persuade or influence others, esp. the exploitation of figures of speech and other compositional techniques to this end" (Oxford English Dictionary). Call it type B rhetoric. Here, we need to keep in mind that efforts at persuasion/influence may, and often do, target, among other things, how one's audience evaluates one's skill with words. Maybe I want you to vote for me, and so my speech uses logic, examples, and figures of thought and speech designed to win you over to my cause. That's rhetoric. But maybe I want you to admire me for my way with words — "Boy, they're a good speaker!" That's rhetoric, too.

In the world that Aeschylus grew up in, the formal study of rhetoric did not yet exist. Still, Aeschylus' plays hardly lack for it. By Euripides' time, the teaching of rhetoric and the art of argumentation had become a specialty of teachers known as "sophists." By Seneca's time, rhetoric formed the cornerstone of elite education at the advanced level and had come to figure prominently in the serious drama of playwrights like Seneca.

How to sniff out type B rhetoric? As we are not studying these plays in the original language, we can't do a deep dive into stylistics and similar. (Yes, literary style is an aspect of rhetoric.) We have, though, spent a lot of time (a whole lot!) with rhetorical features like those mentioned at the beginning of this entry. We've also looked at imagery (simile, metaphor) and allusion (especially mythological comparison) as literary-rhetorical features.

As for a fail-safe acid test for type B rhetoric, I'm not sure one exists, but to paraphrase the late Potter Stuart, you'll likely know it when you see it. You can think of type B rhetoric as going beyond straightforward or ordinary statement. When Antigone in Sophocles' play of that name says, "But think of Niobe — well I know her story," she could have just said, "They're gonna wall me in." Instead she uses allusion to say something like, "Like Niobe, I will be killed in a way — walled in — that will live forever in story!" (Note that the Octavia is notably rich in comparison and mythological and historical allusion of this type.) When Medea says, "To my mind, the glib hypocrite / is the lowest scoundrel of them all. The more he glozes falsehood with his tongue, / the more brash he grows in villainy, / but ends up by not being very clever," she is saying that Jason's skill with persuasive argument is, basically, no match for hers. In calling him out as a sophist, she is showing herself to be a consummate sophist.

Rural Dionysia. See "Dionysia."

Salamis. An island near Athens. The Straits of Salamis was where the Battle of Salamis, in which Greece defeated the Persian fleet, was fought (480 BCE). Aeschylus' Persians is basically about the Battle of Salamis, or "Salamis" for short.

satyr. Mythical beast, usually male, combining features of horses (or goats) and human beings. Satyrs were closely associated with Dionysus; dancers dressed as satyrs might take part in Dionysian processions. Satyrs also formed the choruses of satyr dramas.

satyr drama. A form of tragedy, and perhaps the origin of tragedy, that featured fun, frolic, and a chorus of satyrs. At the Classical Athenian Greater Dionysia, satyr dramas typically formed part of a single playwright's bill of four plays (tetralogy) in competition over the course of a single day. Satyr drama came last in the sequence and lightened the mood. (Because humorous, satyr drama resembles comedy, though it is better thought of as funny tragedy.)

Semnai Theai. At Athens, the Semnai Theai, the "Revered Goddesses," were worshiped at a spot near/under the Areopagus Hill. They were associated with the just punishment of crime. In Aeschylus' Eumenides, it is the name given to the Furies once Athena has recruited them to carry our their old function in behalf of her city (Athens). Only now, they fulfill that function within the context of state-organized punishment and deterrence of crime.

Senecan schema, Senecan formula. To explain the relationship of plot to theme in Senecan tragedy, C.J. Herington lays out what he terms its "scheme," what I'll call the "Senecan schema" or "formula"; for more on this, see the Seneca Phaedra Study Guide.

sententia, plur. sententiae. The Latin noun sententia can simply mean the "sense" of an utterance, the "thought" that it seeks to convey. But the term also has a technical meaning pertinent to the study of Roman tragedy. In the poetic and rhetorical stylistics of the imperial period (27 BCE onward), sententia comes to the fore as a term describing a short sentence dense with significance and often (not always) saturated with irony.

This mode of expression was not a Roman invention. Greeks, whose gifts to Rome included the art of rhetoric, had their own gnomai (Greek), their own sententiae (Latin). So, for instance, in Aeschylus' Libation Bearers, when a perplexed Orestes asks his friend, Pylades, what to do, the latter declares, "Make all mankind your enemy, not the gods" (p. 217, Penguin edition). That's a sententia. Expanded, it means, "Do not fail to carry out the task laid on you by the god Apollo, namely, to kill your mother, lest you suffer the consequences of your disobedience to my command."

On the Roman side, we start seeing memorable sententiae already in tragedy of the Republican period, for instance, one I've dubbed "the tyrant's creed":

oderunt dum metuant. "Let them hate so long long as they fear." (Accius Atreus, ca. 100 CE — for the tyrant, fear is the most efficient and reliable route to procuring obedience)

That sententia had an afterlife of imitation/adaptation in early Imperial Senecan and Pseudo-Senecan tragedy:

"Men compelled by fear / to praise, may be by fear compelled to hate." (Minister in Seneca Thyestes — tyranny forces resistance and rebelliousness to hide behind a screen of adulation. Thus the tyrant can trust no one, is always in danger)

"Let him be just who has no need to fear." (Nero in Pseudo-Seneca Octavia — kind of picking up on the previous sentiment, Nero acknowledges that tyrants like himself must shrink from nothing to keep themselves in power)

Still another sententia, one describing ambition as a kind of insatiable hunger, runs as follows:

"A man who can do much would like to do / More than he can." (Nurse in Seneca Phaedra, Penguin p. 106; she is commenting on Theseus' overweening ambition in wanting to kidnap Proserpina, the Queen of the Underworld.)

Looking at the original Latin, you see just how compact and verbally clever the line is:

quod non potest vult posse qui nimium potest (line 215)

In Senecan tragedy, sententiae can come thick and fast, stichomythia-fashion, in places where a character embodying the voice of reason debates another embodying the voice of passion.

silen/Silenus, Papposilenus. Pretty much the same thing as a satyr. In satyr drama, (Pappo)silenus is one of the regular characters, an elderly satyr and father of the other satyrs.

skene. In a Greek theater, the "stage building" serving as backdrop to the stage platform. It could represent a palace, cave, etc.; it could offer entry to the stage through a door; its roof could serve as cliff-top, heaven, etc.

sophist, sophistic. Prior to the later 400s BCE, a sophist was a "wise man," one who stood out for sophia, wisdom or skill. By about 430, sophistēs ("sophist") had come to refer to a professional (i.e., paid) teacher of subjects of interest to young men intending to enter public life. "Sophistic" was what a sophist did. These terms could carry negative connotations; to ordinary Athenians, they seem to have suggested instruction in the art of verbal deception. They matter to our course because ancient Athenian drama, especially the plays of Euripides and of Aristophanes, feature a great deal of debate and discourse generally imitating or evoking the sophists.

- The students of sophists were, so far as we can be sure, all men. But at least one sophist, in this case, a teacher of rhetoric, was a woman, namely, Aspasia, companion of important Athenian politicians, most notably, of Pericles.

sparagmos. Greek, "tearing of flesh," "dismemberment." In sources, associated with the omophagia, raw eating (which see) of an animal like a fawn or panther, and supposedly practiced in association with the worship of Dionysus. But it is not clear that this was ever actually done.

stasimon. Stasimon (plural stasima) is a technical term defining a part of an ancient Athenian tragedy. It's a choral song (it's not spoken), one coming after the entry of the chorus and before its exit; it is sung by the chorus in common. Stasima, we know, weren't just just sung; they were danced to. As such, it constitutes a formal part of a tragedy. So, for instance, in Sophocles' Antigone, we speak of stasimon 1 (the "Numberless wonders / terrible wonders" chorus), stasimon 2, and so on.

Stoicism was a Greek philosophy embraced in Rome during the late Republic and especially under the early Principate. It addressed a wide range of topics and made important contributions to logic, metaphysics, etc., but what mattered most to Romans were its ethical teachings: fortitude in the face of adversity, the virtuous life as shaped by reason and lived in accordance with nature, and so on. The tragic playwright Seneca was a Stoic, and his plays arguably engaged Stoic themes; see more on the Seneca Phaedra study guide.

stichomythia. In drama, dialogue consisting of speeches of one line or less assigned each character, producing a rapid back-and-forth.

suppliant drama. A drama in which a character or characters come to a city seeking aid and/or protection. There is often suspense involved: How will it all turn out? Aeschylus' Eumenides, Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus, Euripides' Cyclops.

supplication, supplicate, suppliant. Frequent in tragedy, supplication refers to the process of requesting aid or salvation from a mortal or god ("Save us, O Zeus!"). It often involves ritual elements: kneeling down before an intended source of aid, grabbing her or his knees, stroking the chin, approaching while bearing the symbols of supplication, often a tree bough with woolen fillets hanging from it. To "supplicate" is to engage in supplication. A "suppliant" is one who supplicates. Sophocles' Oedipus the King opens with a just such a scene of supplication.

tetralogy. The four plays, three tragedies and a satyr drama, that a finalist in the tragic competition would stage in a single day at the Greater Dionysia at Athens.

theates. Greek: "viewer," "spectator," "audience member."

theatron. Root of the English word "theater," Greek theatron means literally "viewing instrument." It originally referred only to the audience-seating area in a theater, later, to the theater as a whole.

thiasos. Term for a formally organized group of Dionysus' worshipers or followers — like a congregation.

thumele. The "altar" typically set in the middle of the orkhestra of an ancient Greek theater, and often made use of in the action of a play.

tragic cycle (cycle of suffering/violence/retribution, etc.). The idea, prominent in (though not confined to) Greek tragedy, that misdeeds engender further misdeeds/misfortune, whether in the form of vengeance prompting further vengeance, or by visiting the sins of the ancestors on descendants. Not infrequently, the committing of a misdeed is understood as punishment for some previous misdeed — "crime begets crime."

tragic formula. See "ancient law of hubris and ate."

tragoidia. Greek for "tragedy," the word appears derived from "goat song."

thyrsus. Long stalk of fennel (like a very long celery stalk), or arguably a sturdier vegetable, topped with bunched ivy, and wielded by Dionysus and his maenads.

trope of decline. By "trope of decline," I mean a thematic motif present already in early Greek literature (Hesiod especially), though one prominent in Roman literature and meaningful for Roman audiences. The "trope of decline" involves the partly mythological, partly ideological conceit that "our" age (i.e., the Roman "now") represents a devolution from a more innocent, a "better" past. By calling it a "trope," I'm basically flagging it as a rhetorical feature.

Mythologically, the "trope of decline" is mostly the same as the "four (sometimes five) ages of humanity":

- THE GOLDEN AGE, when Kronos-Saturn still reigned, and human beings lived long, trouble-free lives without the need of technology (agriculture, seafaring), politics, or warfare — when people and gods freely interacted. Think of it as humanity's childhood.

- THE SILVER AGE, still a good time, though not as good as the previous.

- THE BRONZE AGE, a time that saw strife come to the fore, though also heroism and nobility.

- THE IRON AGE, always understood as OUR age, a time of political and social strife, struggle to survive, moral chaos.

Thus the myth of the ages can be coupled with a trope of progress, with technology (farming, tools, weapons, navigation) playing a role in the loss of innocence.

In Roman literature, this myth of the ages can be (as it clearly is in pseudo-Seneca's Octavia) coupled with a notion of Roman history as decline from an ideal past (the "good" kings Romulus, Numa, Servius; Republican heroes like Brutus and Cincinnatus, even a "good" emperor like Augustus) to a decadent present ruled by passion, and forgetful of Roman values — an age like that of Nero. See also "empyrosis."

tyrant, tyranny. While this is a term familiar in modern usage, its ancient resonances deserve mention. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, tyranny (turannis) could count as any or all of the following:

- A ruler holding unusual or extraordinary power, a sovereign whose word cannot be overridden

- A ruler with no really valid claim to sovereign or supreme power, but holding it by force

- A ruler exercising rule in a capricious, paranoid, or cruel fashion