Journal Prompt

Aeschylus' Persians, unlike most ancient Greek tragedy, is a history play. Set in Susa, in the heart of the Persian empire, thousands of miles from Greece, it tells the story of the Battle of Salamis, fought in 480 BCE within sight of the city of Athens, just eight years before the play's first production.

- In that naval battle, Greek allies won a decisive victory over a Persian armada.

Aeschylus' Persians tells the story from a Persian perspective. To many modern readers/viewers, Persians is, in fact, a moving work of art; we feel for the suffering of loved ones left behind by the Persian fallen.

"And it tells that story from a Persian perspective." Does it, though? For Edward Saïd, author of the landmark study Orientalism (1978), Aeschylus' Persians "obscures the fact that the audience is watching a highly artificial enactment of what a non-Oriental has made into a symbol for the whole of the Orient" (p. 21).

So is the play a universal statement or a culturally specific, even problematic, document? What if we're Athenians watching the play for the first time, in 472 BCE? Maybe we were there, at the Battle of Salamis, just as the playwright probably was. Does that affect how we react to events staged and narrated before our eyes? Is this a tragedy in the Aristotelian sense: reversal, recognition, pity, fear, catharsis, etc.? Does it reduce to any one thing?

Text Access

Aeschylus. Persians. Trans. Janet Lembke and C. J. Herington. Greek Tragedy in New Translations. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981. (Available via bookstore. Or Kindle.)

Aeschylus' Persians: Introductory Comments

This play may be unlike any other you've ever read, seen, or performed. There are individual roles, but the main role goes to the chorus, while the action on stage is, to a significant degree, concerned with stage-managing the narration of events off stage, sort of like one, big messenger speech.

So in reading, you're going to want to think about, among other things, staging: how to make a play as stiffly hieratic and ceremonial as this one come alive.

Think also about what themes might have registered for its original audience of Athenians. For if we can be sure of one thing, this play was a huge hit! (It received the highly unusual distinction of an authorized re-performance.) The tyrant of Syracuse (Greek city on what is now the Italian island of Sicily) also wanted it staged when Aeschylus visited there.

Think, finally, about the kind of thinking that, scholars argue, this play and related literature have given rise to, specifically with reference to audience identification and the Us/Other opposition. To quote Rebecca Kennedy citing/quoting Edward Saïd's Orientalism,

. . . Said sees a play like Aeschylus' Persians as an example of the Orient being transformed from a very "distant and often threatening Otherness into figures that are relatively familiar (in Aeschylus' case grieving Asiatic women). The dramatic immediacy of representation in the Persians obscures the fact that the audience is watching a highly artificial enactment of what a non-Oriental has made the symbol for the whole Orient" (21). (Classics at the Intersections, "Orientalism and Classics")

Put differently, what is it for actors to be playing, and therefore appropriating, their Other — men playing women, Greeks playing Persians, Us playing Them — in this and other ancient Athenian plays? And what about this play's celebration of defeating that Otherness: how does one do justice to the power, even the beauty, of the play's rhetoric without enabling a kind of malevolent gloating, without succumbing to the worse angels of our nature?

Play Facts

Playwright

- Aeschylus, 525/4 (?)-456/5 BCE

- Athenian, member of a noble family

- Fought in Persian Wars (Marathon, 490; probably Salamis & Plataea, too, 480-479)

- First productions, early 400s

- First victory, 484

- Visited Sicily between 472-468, ca. 458-death

- Perhaps 90 plays, of which 7 (6?) survive, depending on whether the Prometheus Bound is authentically Aeschylus'

Play

- Produced Greater (aka City) Dionysia, March 472 BCE

- Tetralogy:

- Phineus

- Persians

- Glaucus of Pontiae

- Prometheus (satyr play, not the Prometheus Bound)

- The tetralogy as a whole won first, Persians was awarded the distinction of an authorized re-performance

- Scene: Susa, royal city of the Persian empire, before a building, perhaps the royal palace. In front of the building is the grave of Darius

- Cast of characters:

- Chorus of Persian Elders

- Atossa, mother of Persian king Xerxes, widow of the late king Darius

- Persian Messenger (bearing news of the defeat suffered at Salamis)

- Ghost of Darius (Dar-EYE-us)

- Xerxes (ZERK-sees)

Historical Context: Persia v. Greece

This is the only "history play" to survive intact from ancient Athens or from anywhere in ancient Greece. Like the two others we know of (viz., Phrynichus' Phoenician Women, the same playwright's Capture of Miletus), it deals with the great struggle between Greece and Persia in the early years of the 400s BCE.

By the time of that conflict, Persia had conquered a vast empire stretching from the banks of the Indus River, in what is now Pakistan, all the way to modern Egypt, Libya, Turkey, and parts of Romania and Bulgaria. Thus by the time of the first of two Persian invasions of Greece proper, in 490 BCE, Persia already had conquered many Eastern Greek cities and regions in Thrace and Asia Minor (now Turkey).

Given the foot-hold Persia had already established in Europe, and given the nuisance Athens had made of itself by supporting the cities of Ionia in their revolt against Persian rule (499-494 BCE), Darius, the Great King of the Persians, decided to send ships and men to Greece to explore possibilities of further conquest. That expedition led to what we now call the PERSIAN WARS (490-479 BCE), a conflict with important implications for, among other things, Greek national identity.

That war's battles include some that resonate today, including Marathon, which gave its name to a footrace; Thermopylae, subject of the film 300; and Salamis, the subject of Aeschylus' Persians and of 300's sequel.

Here follows a brief outline of the war:

499-494. The Ionian Revolt, rebellion by the Ionian Greek cities of western Asia Minor (now Turkey) against the empire of the Persians. Athens actively supported the Ionians in that revolt.

494. The capture and destruction by the Persians of the Ionian Greek city of Miletus on the western (i.e., Aegean) shore of what is now Turkey.

492. The destruction of Miletus — for the Greeks, a calamity of untold proportions — was the subject of Phrynichus' tragedy The Capture of Miletus, likely produced in 492, just two years after the event. We're told that the play upset the Athenians, still convulsed by the disastrous outcome of the Ionian Revolt, so much that the audience burst into tears, the playwright was fined, and the play was forbidden to be performed ever again.

490. Darius' exploratory incursion into Athenian territory. Battle of Marathon, won by Athens.

483. Xerxes hews a canal through the Athos Peninsula.

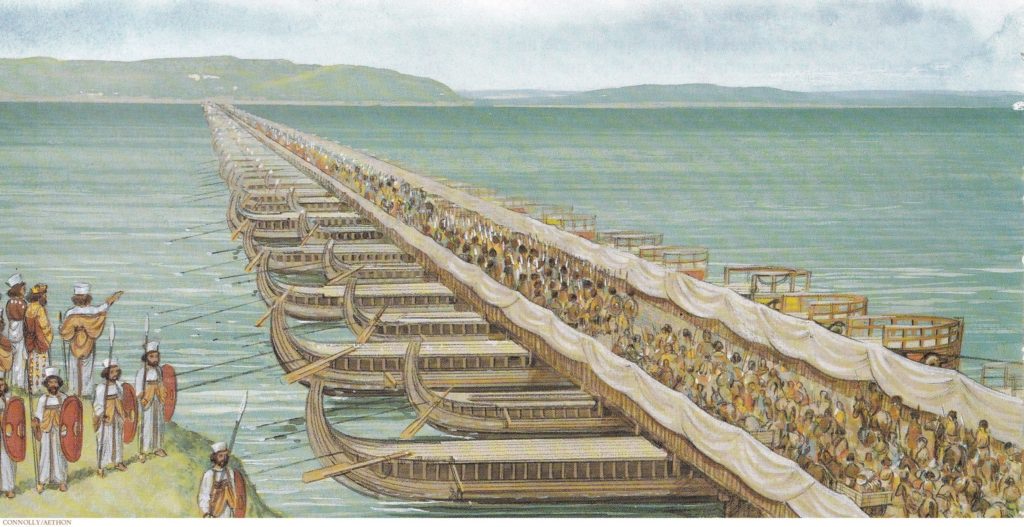

480. Xerxes has a pair of pontoon bridges built to span the Dardanelles, thereby connecting Asia to Europe. Xerxes in person leads his armies across those bridges from Asia to Europe (from what is now Asian Turkey into European Turkey). His ships sail to Greece hugging the shore and passing through the Athos Canal.

Xerxes encounters a Spartan army (the "300") under Leonidas at the pass of Thermopylae. Through treachery, the Spartans are killed to a man. Xerxes marches unopposed into Athenian territory.

Athens is evacuated ahead of the Persian army, which destroys it. Xerxes is tricked into giving naval battle under adverse conditions near the Athens-held island of Salamis. Alarmed, Xerxes withdraws back into Asia with part of his army and what remains of his fleet.

479. The other part of Xerxes army is defeated by Sparta and other Greeks at the land Battle of Plataea. The rest of Xerxes' fleet is destroyed at the Battle of Mt. Mycale (western coast of present-day Turkey).

476. Phrynichus' play the Phoenician Women, named from the chorus of Phoenician woman bewailing the loss of their Phoenician (modern Lebanese) fathers, husbands, and sons at the Battle of Salamis, produced at Athens. Basically the same theme as Aeschylus' Persians.

472. Aeschylus' Persians produced at Athens.

Historical Context: Athens

Athens at the time was one of the two leading states of Greece, the other being Sparta. Greece, it should be pointed out, was no, single, unified entity politically, but a collection of independent city-states (poleis) and ethnicities.

As for Athens itself, it was, as our play notes, neither a kingdom nor subject to any other power. ("They're not anyone's slaves or subjects," p. 51.) It was, rather, a direct democracy. All adult citizen men (not just property holders) had full rights to vote, and many will have had access to high office. At the time in question, the leading politicians included Themistocles, architect of the victory at Salamis, and alluded to (not by name) in the play in connection with a famous deception orchestrated by him (57).

Play: Themes

This play may qualify as "historical," indeed, recent history from the perspective of its original audience. But its world view is thoroughly mythological. The Persian kings are treated as gods; Darius' ghost is likewise a divinity; divine forces shape the action at every turn. Notes C. J. Herington, it is through the eternal and the divine that the human here is to be understood.

That has a great deal to do with what may be the play's leading theme, what Herington terms the "the ancient law of hybris and ātē," through which anything "unduly great" is cut down to size.

In class, I'll be lecturing on how that plays out in the Persians in relation to what I, drawing on Herington, call, at the risk of oversimplifying (and I don't like the name I've come up with), the tragic formula: a poetic-theological framework through which archaic and classical Greek poets like Aeschylus relate human misfortune to cosmic forces.

This "formula" can be said to feature the following elements, which look for in our play:

Koros. Abundant or excessive wealth, success, goods of any sort, and such as would breed. . .

Hubris. Either the kind of arrogance/insolence we associate with wrongdoers, or the acts themselves betokening such an attitude. Less a matter of purely moral badness, hubris is any attitude, word, or act betokening errant disregard for the status or dignity of another, whether human or god.

Atē ("AH-tay"). This is either the madness or delusion leading human beings to self-inflicted ruin, or ruin itself.

Dikē ("DEE-kay"). Dikē means "justice." The word does not show up in Aeschylus' Persians (it does in his Oresteia). But we can still see it as operative in Persians, where we can understand dikē as the re-balancing of a human-divine or human-human imbalance created by human koros and hubris. That makes dikē both the aim of tragic action and the process through which it achieves that aim.

Action (Summary)

Aeschylus' Persians isn't always so very easy to follow. Especially in its opening sections, the extremely poetic diction (the translation accurately maps the Greek in that regard) can make it hard to divine what's being narrated.

So, the action is as follows. The Persian elders, left behind after the youth of Persia and its empire have gone off to fight under their king, Xerxes, in Greece, await news. We learn all this during the parodos, the Chorus' entrance number, which serves as the first scene of the play (no prologue). After the parodos, Atossa, mother of Xerxes, comes out to tell the Chorus her dream and to seek advice. The Chorus advises her to pray for help from the gods.

A Messenger then arrives; he narrates in excruciating detail the naval defeat suffered by Persia at the Battle of Salamis ("Ajax's sea-pelted island," in the words of the Messenger). Note the gruesome vignette of the battle for the Island of Pan (in the straits of Salamis) — the savage slaughter inflicted by Greeks on Persians there.

Atossa leaves the stage while the Chorus performs by itself. The queen then returns with offerings for the grave of Darius, whom she and the Chorus summon forth from the world below.

Rising from the grave, Darius' ghost receives the bad news. Then comes the return of the defeated Xerxes; he and the Chorus lament their losses.

Atossa's Dream

The dream that Atossa narrates to the chorus is laden with foreboding. It has two dimensions: one historical, one mythological. Historically-factually, it seems to have to do with the pair of pontoon bridges, commissioned by Xerxes, and connecting Asian (i.e., Turkish) Abydos on the Hellespont with European (Thracian) Sestos.

Those bridges were an engineering wonder. A two-kilometer-long structure spanning the swift-moving currents of the waterway dividing Europe from Asia, they consisted of anchored ships with a road-bed built atop each, to allow armies, cavalry, and supply trains to pass.

Yet within our play's dramatic horizon, the project takes on mythological significance. As an attempt to yoke together landmasses that the gods had intended to stand apart, the bridges become an act of hubris. Springing from Xerxes' overweening ambition, they defy divine dispensation and risk incurring divine wrath.

What of Atossa's dream? In her dream, Atossa sees two sisters: one in Persian garb, one in Greek. They are yoked together to draw a chariot driven by Atossa's son, Xerxes. The Persian sister draws the chariot without protest; the Greek sister rebels and causes Xerxes' chariot to overturn, with Xerxes' deceased father, Darius, looking on.

Think about the dream's imagery. What does each of the sisters represent? What, the yoke and chariot? What, the toppling of the vehicle? Some of it may seem obvious, but other aspects — gender-related, ethnic, and so on — likely will require thought. How, after seeing the dream, does Atossa react to the portent of the eagle and the hawk? What does it mean to her?

We'll discuss in class. . . .

Word Notes

Bruit. (p. 20) "To spread as a report or rumour; to report(OED).

Kissa. (p. 20) A region of southern Persia.

You, Amistres etc. etc. (p. 40) This catalogue of commanders lists real (and a couple of possibly made up??) names of Persian commanders in the expeditionary force sent to conquer Greece. As a catalogue, functions a bit like a messenger speech and recalls book 2 of Homer's Iliad. "You" etc. The rhetorical figure of directly addressing someone absent is called apostrophe.

mother (p. 49). Not literally the chorus' mother; used as a term of respect.

Memphis. (p. 40) A city in Egypt and part of the Persian Empire.

Lydian thousands, Mysia. Lydia and Mysia were Persian conquered territory in what is now Turkey.

Babylon. (p. 41) A capital of ancient kingdoms, Babylon was located in what is now Iraq.

The strait that honor's Hellē. (p. 42) This refers to the Hellespont and the pontoon bridge over it; see above. You can look up the myth of Helle for yourselves.

Teeming Asia's headstrong lord. (p. 42) Xerxes.

spearmen trained for close combat. (p. 42) Greek land soldiers of this period were typically armed with long spears and were trained to fight is line-of-battle or square formations called phalanxes.

Blind Folly. (p. 43) This translates atē, for which see above.

prostrate yourselves. (p. 45) Just for clarity, prostration is when you throw yourself down on your stomach to honor a revered personage.

and born also to mother a god. (p. 45) The supposed god here is Xerxes. But Persians very much did not worship their kings as gods. So what's the playwright doing?

the fear that vast wealth etc. (p. 46) In the archaic-poetic Greek worldview, the wealth and plenty that place the "lucky" individual in danger of a terrible reckoning is koros.

Eye (p. 46). Atossa to the chorus: "My fear / centers on the Eye, / for in my mind / the house's Eye / is its master's presence." In Greek, the word for "eye" (ophthalmos, omma) can express that which is most precious — as in the "apple of my eye." Here, that "eye" is what is most precious to the house of Xerxes, namely, Xerxes himself. Atossa fears that the wealth and power of that house — her family — could imperil this most valuable of possessions.

Phoibos (p. 48). That's the Greek god Apollo. The play has many "foreign" touches meant to evoke a non-Greek setting. But the Greeks typically understood the rest of the world as worshiping, basically, the same gods as they.

The eagle and the hawk. (pp. 48-49) This is something that Atossa sees while awake, yet it, like her dream, is a god-sent vision, an omen. The eagle is the bird of Zeus, king of the gods. The Persian king is like the "Zeus" of his empire. This is Xerxes being harried by the weaker Greeks.

a fountain of silver. (p. 51) Athens actually possessed at this time an abundance of mineral wealth in the form of a silver mine.

But who herds the the manflock? (p. 51) A lightly veiled reference to the fact that Athens at this time is, unlike lands subject to Persian rule, a democracy.

Listen! cities that people Asia. (pp. 52 ff.) This messenger scene recounts the Battle of Salamis (see above) and, despite its highly poetic and mythologized manner of telling, is a source of data for historians.

Mede. (p. 51) The Medes were, like the Persians, a people of ancient Iran; they were culturally and linguistically close to the Persians. At first, Medes ruled over Persians. Then, starting with Cyrus the Great (ruled 559?-530 BCE), Persians ruled Medes. Greeks did not always make a strict distinction between Medes and Persians.

Sileniai's raw coast. (p.54) Seems to be part of the coastline of the island of Salamis.

"Ajax's sea-pelted island" (p. 54) is Salamis. Salamis is an island hugging the coast of Athenian territory; it's where the battle of Salamis was fought. Ajax was a hero from the island.

Artembares, etc. etc. (p. 54 and throughout) The litany of Persian names, in the messenger speech and elsewhere, is important. It's hard to know if each one of these was a historical personage; several certainly were. But as K.O. Chong-Gossard helps us understand, the Greekified (Hellenized) spelling and pronunciation of these non-Greek (Persian and non-Persian) names appropriates and normalizes for a Greek audience realities that were deeply and intriguingly foreign. At the same time, reciting the names of the dead can, as at a 9/11 memorial, have a comforting effect on the living.

Numbers. (p. 56) The messenger counts 300 ships fighting for the Greeks and 1,000 fighting for Persia. We can't know the actual numbers, but maybe (this is extremely non-authoritative!) 300-400 on the Greek side and 600-1,000 (???) on the Persian side. Some ships fighting for Persia will have been Greek (subject states); many will have been Phoenician (= Lebanese). Persia did not have its own ships fighting at this battle, one fought far from Persia and Persian shores.

Something vengeful (p. 57). Divine forces are at play in this telling.

For a Greek came in stealth from the Athenian fleet. (p. 57) Themistocles, the Athenian commander, is said to have pretended to betray the Greeks, whispering to Xerxes (via a servant) that the Persian king should attack before the Greeks could escape. That tricked Xerxes into giving battle under conditions fatal to his fleet, that is, in the narrow straits within which the Greek ships were moored. By attacking the Greeks first, the Persians (a) guaranteed that none of the Greeks who wanted to escape could do so. But the straits were narrow enough that (b) superior numbers were no advantage to Persian forces. Hemmed in and unable to back up, Persian ships became easy prey for the Greeks. Aeschylus makes no mention of the fact that Xerxes entered an abandoned Athens (they'd fled to Salamis) and destroyed the city.

At first the wave of Persia's fleet rolled firm. . . . (p. 59) Herington identifies this as the point in the play that reversal, Aristotle's peripeteia, happens: as the Persian fleet falls into the Greek trap.

Good friends, whoever lives. . . . (p. 68) This speech by Atossa is the start of the great conjuring scene, where the queen, assisted by the cries of the chorus, summon the ghost of Darius from the grave, to break the terrible news to him. This whole scene is a terrifying testament to the "strength of words" (Aeschylus Libation Bearers) — words, that is, as things that do things. The chorus here plays a role fully enmeshed in the action. There's a similar scene in the same playwright's Libation Bearers.

Too swiftly then the oracles came true. (p. 76) The gods had already predicted disaster for Darius' family — why? Darius had hoped that fulfillment would come later — what hastened it? (Darius answers that.) And again, if things are fated, where does that leave human agency?

and there they linger. (p. 80) That is, much of Xerxes army remains in Greece, in Boeotia, not far from Athens. That remnant will be crushed in the Battle of Plataea, 489. Darius is predicting a second defeat for his son. Yet another defeat will strike Persia's ships near Mount Mycale, on the other side of the Aegean.

GOD PITY US. (p. 82) The rest of the play, with the chorus and Xerxes, is chanted and sung as a great kommos, a grieving scene of the sort that Greek tragedy often ends with.

your very own Eye (p. 88). This is a different sort of eye from the one on p. 46. The Persian king's spies, called his "eyes and ears," were tasked with making sure provincial governors and such functionaries behaved themselves.

And keep striking breasts . . . And tug, pull out white hairs . . . with tearing nails . . . And rip heavy robes. (p. 92) These are actions signifying violent grief. The word kommos comes from koptō, "beat."