These are grammar concepts used in teaching ancient Greek. The examples, though, come mostly from English.

We use these concepts not to burden students unnecessarily. Indeed, none of this is going to be tested. Rather, it's to help make the learning process more efficient. And there's nothing wrong with learning a little grammar!

Word Groups

sentence. A group of words that together express one or more complete thoughts. Complete sentences can stand on their own; they don't feel as if they're lacking something.

These are sentences:

- "I am your teacher"

- "When you go out, please close the door"

- "I saw the movie, and then I went home"

These are not complete sentences:

- "Your teacher"

- "For you"

- "When you go out"

clause. In English, a clause expresses a thought, though maybe not a complete one. Some clauses are full sentences, others are not. In English, a clause (almost?) always contains a verb. In Greek, the verb may be left out or implied. For instance:

- "I went to bed" (both a clause and a full sentence)

- "When I went to bed, . . ." (a clause, but not a full sentence)

- ὁ Φίλιππος ἀγαθός, ho Philippos agathos, "Philip is good" (Greek often drops the verb "to be")

phrase. A small group of words that go together, less than a clause:

- "For you"

- "The big, round ball"

Parts of Speech

We'll be talking about these parts of speech: nouns, pronouns, articles, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions (particles), exclamations (interjections).

noun. Word naming a person, place, or thing:

- book

- person

- highway

- courage

- Greece

- Jennifer

- Stephanos

pronoun. A word, typically, very short, that takes the place of a noun:

- she

- her

- they

- who

- someone

There are different types of pronoun. I'll use English to illustrate:

- Personal pronouns: "I," "you," "he," she," "it," "they," and their inflected forms

- Demonstrative pronouns that "point" to things: "this," "that"

- Intensive pronouns:

- "She herself" (and no one else, the one and only: "She did it herself," with no one's help, in person)

- "You yourself," etc.

- Reflexive pronouns (similar in form, different in function, from intensive):

- "They help themselves" (they do it to themselves)

- "I help myself," etc. (contrast "I myself help him")

- Relative pronouns refer to a noun or other pronoun (the antecedent), stated or implied, in the clause and introduce relative clauses:

- "They who like ice cream should hurry to the ice cream truck" ("they" is the antecedent of the rel. pronoun "who")

- "The baby that you heard is a newborn"

adjective. A word used to describe, or "modify," a person, place, thing, or pronoun:

- beautiful ("the beautiful picture")

- smart ("she is smart")

- loud ("I like my music loud")

- A special kind of adjective is the participle. That's a verb altered by changing its stem (the part you add endings to) so it can work like an adjective, i.e., can "modify" nouns and pronouns: "The man working in the field." "Working" is an adjective modifying "man." But it's also an action word, a verb, except that its stem, "work-," has had something added to it: "-ing." By adding "-ing," we've changed the stem. We've made the verb into a participle.

Adjectives agree in case, number, and gender with the nouns or pronouns they modify.

article. We'll only be talking about the "definite" article. In English, it's "the": "the book." In Greek, ὁ, ἡ, τό, etc. Greek often uses the article where English doesn't, for instance, to help point out the subject of a sentence.

- ὁ Δικαιόπολις αὐτουργός ἐστιν. Dicaeopolis is a farmer

- ὁ βίος ἐστὶ καλός. "Life is good"

Like adjectives, articles agree with their nouns in case, number, and gender.

verb. A word expressing an action or a state:

- She runs fast

- He sleeps a lot

- Eat your food!

- I am happy

adverb. A word describing ("modifying") a verb, adjective, or other adverb. Some adverbs express time or place. Others express manner:

- He runs slowly

- The book is very interesting

- Run very fast!

- Come home tomorrow

- I'm staying here

particle/conjunction. I.e., linking words.

Regular conjunctions (linking words), English:

- and

- but

- or

Greek particles. Greek has a number of short words, most of which never come first but second or third in the phrase / clause / sentence. These are called particles because they're little words — little but tremendously important:

- δέ — "and" or "but" (post-positive, doesn't come first)

- οὖν — "so," "and so," "therefore" (post-positive)

- γάρ — "because," " 'cuz," "for" (post-positive)

- Not "This is for you," but "He loves his life, for (= because) he is a farmer and free"

- καί — "and" (not post-positive)

- ἤ — "or" (not post-positive)

- ἀλλά — a strong "but," "rather," "instead" (not post-positive)

- (etc.)

Subordinating conjunctions. These are words that introduce "subordinating" clauses that offer context:

- When the Saints go marching in, I want to be in that number

- I want to show you where the money is

preposition. Prepositions come before a noun or pronoun and express a relationship between that noun/pronoun and something else. Preposition + noun or pronoun = prepositional phrase:

- She dances with her friend

- He dances on the floor

- They arrived after you

Exclamations (interjections):

- Wow!

- Hey, teacher!

- In ὦ διδάσκαλε, ὦ is a kind of exclamation. ὦ = "Hey" in English.

Sentence Parts, Sentence "Roles"

Sentences in English and Greek are divided into different parts, with words and phrases playing special "roles," like actors in a movie or players on a sports team. Note especially the following roles:

subject. The noun, pronoun, or noun phrase ("the barking dog") that the sentence is all about, the star of the show, who or what's driving the car. Subjects often (not always) "do" the action or state:

- He is a teacher

- She drives the car

- The cat chases the mouse

linking verb. Linking verbs connect subjects to complements. The most common linking verbs in English are "to be" and "to become." In Greek, that's εἰμί (eimi) and γίγνομαι (gignomai).

- She is a police officer ("she" subject," "is" linking verb, "police officer" complement)

- He became a teacher

complement. A complement is what "completes" a sentence with a linking verb. It is usually a noun or adjective:

- She is a police officer

- He became a teacher

- Be good!

intransitive verb. An intransitive verb expresses an action or state that involves no target of the action/state (no direct object):

- The dog is sleeping

- The cat is running

transitive verb. A transitive verb expresses an action that targets someone or something (the direct object):

- The dog is chasing the mouse

- Jane rang the bell

- Achilles killed Hector

direct object. The person or thing targeted by a transitive verb:

- The dog is chasing the mouse

- Jane rang the bell

- Achilles killed Hector

NOTE: The complement of a linking verb and the direct object of a transitive verb are two, entirely different things. In Greek, they will (except in certain special situations) be in entirely different noun cases (nominative for complements, accusative for direct objects).

indirect object. The person or thing that an action relates to or that it's for, but isn't directly targeted. In English, often (not always) expressed by a prepositional phrase; in Greek, by the dative case:

- Jane gave the money to her mother

- Give me the money

Parts of Words

Not all words can be broken up into parts, but many can.

compound words. Compound words are made of more than one word: "bookstore" = "book" + "store."

root. A word root is a word boiled down to its single most essential element, with nothing added to it before, after, or inside. In English and in Greek, word roots are very short, often no more than two consonants plus a vowel. Roots can travel between different parts of speech. Sometimes, the root can function all by itself, as its own little word ("and"). Sometimes you need to add something. New words (aka, derivatives), or new forms of the same word, come from adding to the root:

- sun (root) >

- sun-ny (derived adjective)

- sun-s (plural of the noun "sun")

- sun-ning (gerund form of the verb "to sun")

- go (root) >

- go-es ("you" singular form of verb)

- go-ing (gerund of verb)

Here follows under separate heading more detailed discussion of word parts. . . .

Prefix, Suffix, Infix

Prefixes, suffixes, and infixes are word add-ons that change the meaning or function of a word root.

prefixes. Prefixes are added at the beginning:

- dog-house (house for a dog)

- by-law (a law or rule for a specific place or organization — "by" in the sense of "nearby" or "local")

suffix. Suffixes are added at the end:

- dog-s (the plural "s" says it's more than one dog)

- dogg-ed (= "persistent," as in "dogged determination." The "-ed" is an English past-participle ending, making "dog" into an adjective")

- dog-'s (the ending " 's" makes a noun into a possessive noun)

infix. The term "infix" as a teaching tool makes more sense for Greek than for English. A common verb infix is the vowel iota added inside a verb root, where is creates a present stem. (More on stem and tense below.)

Stem

A stem is the part of a word you add endings to. It might be the root, or it might be root + any number of add-ons (prefix, suffix, infix).

- dog >

- dog's

- dog-s

- dog-s'

- train >

- train-s

- train-ed

- train-ing

- doghouse (compound noun stem) >

- doghouse-s

- etc.

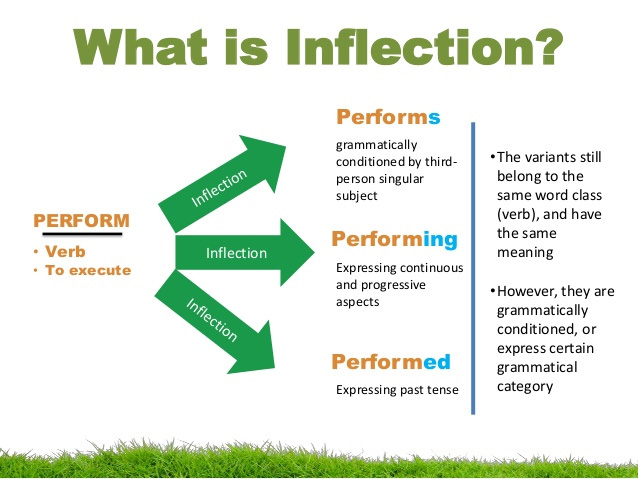

Ending, Inflection

Endings, or inflexions, are added to the end of the stem (they're suffixes), sometimes with changes to the stem.

The image is of a word that bends ("inflects") its ending to repurpose its role and/or function, yet otherwise keep its basic meaning the same.

In English, there is some, but not much, inflection:

- train >

- trains

- trained

- training

- who >

- whom

- whose

We speak of that as changes to the inflected form, or simply, "form," of a word. (The plural form of "dog" is "dogs.")

In Greek, nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, and articles are inflected. Adverbs don't really inflect in Greek, though they kind of do. Noun, pronoun, article, and adjective inflection is called "declension." Verb inflection is called "conjugation."

Grammatical Number

Grammatical number is "how many." It often involves a change of word form. Greek and English have two numbers: singular and plural. One "dog," two-to-infinity "dogs." He "runs," they "run." Number in Greek applies to nouns, verbs, pronouns, and adjectives.

- Greek also has dual number, where two things are involved. We won't talk much about dual number this semester.

Grammatical Gender

English has three genders: masculine, feminine, neuter. Gender in English only affects certain pronouns, where it is highly significant:

- "he" is masculine, for a male person

- "she" is feminine, for a female person

- "it" is neuter, for things

- "they" is often used as a gender-neutral pronoun for human individuals

Nouns. Unlike English nouns, Greek nouns have grammatical gender. Indeed, all nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in Greek are going to be in one of the three genders:

- masculine

- feminine

- neuter

Gender in Greek only means something when you're dealing with words referring to people and animals, where it can coincide with biological sex. Greek for "man," an adult male person, is going to be masculine: ὁ ἀνήρ, ho anēr, "the man" — it's the article that shows the gender. Greek for "woman," an adult female person, is feminine: ἡ γυνή, hē gunē, "the woman" — because the noun is feminine, the article has to be, too. A male dog is masculine: ὁ κύων (ho kuōn). A female dog, feminine: ἡ κύων (hē kuōn).

But all Greek nouns have gender. With places and things, gender means nothing. But we still need to respect it. βιβλίον (biblion) is neuter. Only neuter articles and adjectives are allowed to go with it: τὸ μέγα βιβλίον (to mega biblion), "the big book." οἶκος (oikos), "house," is masculine. οἰκία (oikia) also means "house," but it's feminine. Gender there means nothing.

Nouns mostly (not always) stay in one gender; they don't change. (Animal words can change gender.) Pronouns, articles, and adjectives change gender to go with the noun (stated or implied) that they modify.

- Animate gender for things — humans, animals, other — that could do things independently

- Inanimate gender for really innert stuff: water, rock

Grammatical Case

Grammatical case is the form that a noun or pronoun (plus any accompanying article or adjective) takes to go along with a particular role. Along with number and gender, case is how nouns-pronouns-adjectives-articles are inflected, how they change form.

In English, subjects are in the "subject" case; direct objects, in the "object" case; possessives, in the "possessive" case:

- He is here (subject case)

- She sees him (object case)

- The money is his (possessive case)

Here is an incomplete list of roles that the cases play in Greek:

- Nominative for subject: ὁ Φίλιππος ἐν τῷ οἴκῳ οἰκεῖ ("Philip lives in the house")

- Nominative also for complement: ὁ οἶκος καλός ἐστι ("The house is beautiful")

- Genitive for place from which: ὁ Φίλιππος ἐκ τοῦ οἴκου βαίνει ("Philip goes out of the house")

- Genitive for possession: ὁ τοῦ Φιλίππου οἶκος καλόλος ἐστι ("Philip's house is beautiful")

- Dative for place where: ὁ Φίλιππος ἐν τῷ οἴκῳ ἐστί ("Philip is in the house")

- Dative for indirect object: ἡ Μέλιττα τῷ Φλίππῳ λέγεις ("Melissa speaks to Philip")

- Accusative for place (in)to which: ὁ Φίλιππος εἰς τὸν οἶλον βαίνει ("Philip goes into the house")

- Accusative for direct object: ἡ Μέλιττα τὸν οἶκον φιλεῖ ("Melissa loves the house")

- Vocative, to get someone's attention: ὦ Φίλιππε ("Hey, Philip!")

- Many other uses for cases!

The English-language names of the cases translate those in Latin. (Casus nominativus > "nominative case.") The Latin names themselves translate the original Greek names.

Just for your information (not for any test!), here are some (ancient) Greek grammatical terms with English equivalents:

| λέξις | word | ||

| ὄνομα | noun | ||

| ῥῆμα | verb | ||

| ὑποκείμενον | subject | ||

| κατηγορούμενον | predicate / complement | ||

| ἐπίθετον | adjective | ||

| ἐπίρρημα | adverb | ||

| ἄρθρον | article | ||

| ἑνικὸς ἀριθμός | singular number | ||

| πληθυντικὸς ἀριθμός | plural number | ||

| ὀνομαστικὴ πτῶσις | nominative case | ||

| γενικὴ πτῶσις | genitive case | ||

| δοτικὴ πτῶσις | dative case | ||

| αἰτιατικὴ πτῶσις | accusative case | ||

| κλητικὴ πτῶσις | vocative case |

Noun Agreement

Adjectives and articles must always agree with the case, number, and gender of the noun or pronoun they modify. They reflect, like a mirror, not the sound of its ending but rather the case-number-gender indicated by its form. It's as if you looked in a mirror and saw not your face but your character, your personality, your role in life staring back at you.

Pronouns usually reflect the gender and number, but not necessarily the case, of the noun that they take the place of (the "antecedent").

- ὁ καλὸς οἶκος, ho kalos oikos, "the beautiful house" (nominative case)

- τὸν καλὸν οἶκον, to kalon oikosn, "the beautiful house" (accusative case)

- ἐκεῖνο καλόν ἐστι, ekeino kalon esti, "That's fine/super/good"

- Attention: Agreement is not ending-echo. It's matching the correct form of the article or adjective within its own system of endings to the case-number-gender of the noun or pronoun. ὁ καλὸς γένος is wrong. γένος is neuter. That should be, τὸ καλὸν γένος, "the beautiful kind" (or "type" or "family").

Noun Declension

Declension is the pattern or style of form-changing for nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and articles. We say that a given noun, pronoun, etc. "declines."

It doesn't make a lot of sense to talk about declension in English. It does in Greek, which has three noun declensions, and various mix-and-match patterns for pronouns, articles, and adjectives.

So, a given noun (usually) uses only one of the three declensions (they're numbered one through three). By themselves, declensions don't mean anything. They're the way a given noun changes its "clothes" or "uniform" or style of dress, that is, its endings. You have your preferred style of dress (maybe 60s mod, 70s disco, maybe something more up to date). I have mine. ἀγρός (agros, "field") has its. On a given soccer team, the players don't all dress the same; the goalie usually wears something that differs from the rest. Within a declension, some forms look like others, some forms are very distinct. But they all kind of go together.

Some nouns have irregular declension: each irregular has a more or less unique pattern that you have to learn specially.

Here follows a very basic summary of the chief features of each of the three declensions — for more detail, please see the textbook and course handouts:

- "First declension." For masculine and feminine nouns, no neuters.

- It features the vowels alpha and eta, which is lengthened alpha

- Consonant elements are similar to those of the "second declension"

- Lots of feminine nouns, people and things, concrete (stuff you can hold in your hand) and abstract

- A number of masculine nouns, though mostly for people

- Very slight differences in ending pattern between feminines and masculines:

- κόρη ("girl," fem.)

- οἰκία ("house," fem.)

- μαθητής ("male student," masculine — note the sigma for the masc. nominative sing.)

- "Second declension." Masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns of all sorts. Slight differences between, on the one hand, masc/fem, on the other hand, neut endings. The featured vowel is omicron:

- λίθος, -ου, ὁ ("stone," masc.)

- στρατηγός, -οῦ, ὁ/ἡ ("general," masc or fem, depending on whether is male or female is meant [fem in Aristophanes Lysistrata])

- παρθένος, -ου, ὁ/ἡ ("virgin/unmarried," masc or fem)

- ἄροτρον, -ου, τό ("plow," neut)

- "Third declension." Wide array of masc, fem, and neut nouns, a number of them irregular. Here you have to be careful to note the genitive singular as well as the nominative singular form: the stem can change a lot. The gen sing is -ος (or -ους or -εως). Don't confuse third-decl. nouns with first- or second-declension:

- παῖς, παιδ-ός, ὁ/ἡ ("child," masc/fem)

- ἀνήρ, ἀνδρ-ός, ὁ ("man," masc)

- γυνή, γυναικός, ἡ ("woman," fem)

- γένος, γένους, τό ("kind," "type," "family," neut)

- πρόβλημα, προβλήματ-ος, τό ("problem," neut)

Articles, pronouns, and adjectives mostly (not entirely) draw on each of the three declensions for their forms. But they're more irregular; special care needs to be taken with them.

Noun Parsing

To "parse" a noun, pronoun, article, or adjective is to identify its case, number, and gender. Parsing helps us understand the role a noun or pronoun plays in a clause. It also helps us know what articles and/or adjectives go with that noun (or pronoun).

This really only makes sense for Greek, where the form of a noun flags its function in a clause, and where articles and adjectives "go with" (modify) the noun they agree with (in case, number, and gender).

For instance,

The noun οἶκος in the sentence, ὁ οἶκος καλός ἐστι ("The house is beautiful") is

- nominative (case)

- singular (number)

- masculine (gender)

How do we know this? Because we have an article, we can learn everything from it: ὁ is nominative-singular-masculine. Because it modifies the noun οἶκος, it must agree with it in case-number-gender. (Ditto the adjective καλός.) Its noun (οἶκος), therefore, must be all those things, too.

Noun parsing without articles or adjectives requires that you know or look up the noun to learn what to expect its various forms to be.

Another parsing, this time, no article or adjective to offer clues. Take the sentence οἶκον ἔχω: let's say we want to parse οἶκον. What to do?

- Look up οἰκ- words in the dictionary at the back of the textbook.

- Find the οἰκ- entry that best fits. That will be:

- οἶκος, οἴκου, ὁ. "house," "home." (The verb οἰκῶ, "I dwell," starts the same but doesn't help part from those first few letters.)

- The form οἶκος by itself doesn't tell you much, but. . .

- In combination with οἴκου, the genitive form of the word, you learn lot: that this is a second declension noun. (οἶκος, οἴκου, etc.)

- The article ὁ is there to tell you that it's a masculine noun

- Keeping in mind how second declension nouns decline, we can now deduce that οἶκον is accusative-singular-masculine. οἶκον ἔχω means "I have a house." οἶκον ("[a] house") is the direct object of ἔχω ("I have").

More in the Athenaze text and in online handouts.

Verb Parsing

Verb parsing is to ID a verb's

- tense

- voice

- mood

- person

- number

The form λέγω (of the verb λέγω, "say") is:

- tense: present

- voice: active

- mood: indicative

- person: first person

- number: singular

The form λέγω means "I say," or "I am saying."

Verb Person and Number

Verb endings, especially in Greek but also (a little) in English, agree with the subject in person and number.

- Person is whom the speaker is speaking about

- 1st person: the speaker(s) talk about themselves

- 2nd person, the speaker(s) talk about the person/people they're talking to

- 3rd person, the speaker(s) talk about a person/people outside the speaker--addressee circle

- Number is how many are doing/being the action or state spoken about: one = singular, more than one = plural. (There is also dual number for verbs, which we won't study this semester)

In English, you need pronouns or nouns to clarify person and number:

| sing | plur | |

| 1st | I love | we love |

| 2nd | you love | you love |

| 3rd | he/she/it/Arthur loves | they/the students love |

In Greek, you don't. The endings do the work:

| sing | plur | |

| 1st | φιλ-ῶ | φιλ-οῦμεν |

| 2nd | φιλ-εῖς | φι-λεῖτε |

| 3rd | φιλ-εῖ | φιλ-οῦσι(ν) |

Verb Conjugation

Conjugation is like declension, only for verbs: it's the style of ending-changes that a given verb adheres to, like a sports team. The present tense of the verb φιλῶ ("love") belongs to the epsilon-contract "team." The present tense of the verb λέγω ("say") belongs to the omega-verb "team." Those conjugations are similar, but they still do things differently (note the differences below, and not just in accent), depending what "team" the verb belongs to.

As in the case of declension, the pattern of conjugation by itself doesn't mean anything; it's just an arbitrary fact that you play for the Yankees and I for the Red Socks.

| epsilon-contract | omega verb | |||

| sing | plur | sing | plur | |

| 1st | φιλ-ῶ | φιλ-οῦμεν | λέγ-ω | λέγ-ομεν |

| 2nd | φιλ-εῖς | φι-λεῖτε | λέγ-εις | λέγ-ετε |

| 3rd | φιλ-εῖ | φιλ-οῦσι(ν) | λέγ-ει | λέγ-ουσι(ν) |

As with nouns, so with verbs, some are irregular: you have to learn the pattern of form change specific to the verb in question, as in the case of the English verb "to be," or in Greek, εἰμί.

More than that is difficult to say here, but we'll be talking a lot about it. Plus, you have your textbooks and access to the handouts.

To be continued. . . .